The School of Life - The Sorrows of Work

Here you can read online The School of Life - The Sorrows of Work full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2017, publisher: The School of Life Press, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Sorrows of Work

- Author:

- Publisher:The School of Life Press

- Genre:

- Year:2017

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Sorrows of Work: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Sorrows of Work" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Sorrows of Work — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Sorrows of Work" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The Sorrows of Work

Other books in this series:

Why You Will Marry the Wrong Person

On Confidence

How to Find Love

Why We Hate Cheap Things

Self-Knowledge

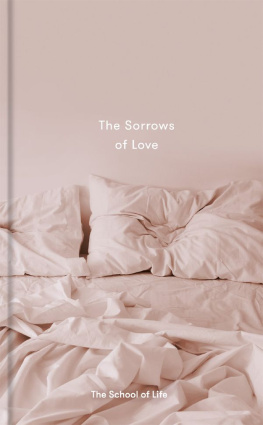

The Sorrows of Love

The Sorrows

of Work

The School of Life

Published in 2017 by The School of Life

70 Marchmont Street, London WC1N 1AB

Copyright The School of Life 2017

Designed and typeset by Marcia Mihotich

Printed in Latvia by Livonia Print

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not be resold, lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without express prior consent of the publisher.

A proportion of this book has appeared online at

thebookoflife.org

Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders of the material reproduced in this book. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publisher will be pleased to make restitution at the earliest opportunity.

The School of Life offers programmes, publications and services to assist modern individuals in their quest to live more engaged and meaningful lives. Weve also developed a collection of content-rich, design-led retail products to promote useful insights and ideas from culture.

www.theschooloflife.com

ISBN 978-0-9957535-1-8

Contents

INTRODUCTION

There is no more common emotion to feel around work than that we have failed. We have failed because we have made less money than we had hoped; because we have been sidelined in our organisation; because many of our acquaintances have triumphed; because our schemes have remained on the drawing board; because we have been constantly anxious and, for long stretches, tired and bored.

We tend to meet our sorrows personally. We believe that our failures are tightly bound up with our own character and choices. But the suggestion here is that the single greatest cause of our professional failure lies in an area that self-aware, moderate and modest people are instinctively loath to blame: the system we live within. Whatever our natural hesitancy, it seems we deserve to recast at least some of the explanations for our woes away from intimate experience and towards large-scale historical and economic forces. Although on a daily basis we are enmeshed in problems (inadequacies, desires and panics) that feel as if they must be our responsibility alone, the real causes may lie far beyond ourselves, in the greater, grander currents of history: in the way our industries are structured, our values are determined, and our assumptions generated. For a long time now, capitalism has been a confirmedly tricky system in which to retain equilibrium, make peace with ourselves, find fulfilment in our work and cope. Its not quite our fault if, rather too often, we feel like losers.

This isnt to make a particular dig at capitalism, or to suggest that there may be easier alternatives at hand. Every economy that has ever existed has been bound up with multiple sorrows. Organising an equitable system of incentives, goads and rewards is as yet beyond us. We should be allowed to level criticisms, not in the name of arguing for an alternative utopia, but in order to depersonalise our sense of failure.

Work disappoints us, not by coincidence but by necessity, for at least eight central reasons:

1. The demand for specialisation limits our potential.

2. The concentration of capital squeezes out personal initiative.

3. The extent of consumer choice forces us to commercialise our work beyond what feels tolerable.

4. The scale of industry robs us of a sense of meaning.

5. Competition generates a state of perpetual anxiety.

6. The requirement for collaboration maddens us.

7. Our high aspirations embitter us.

8. The notion that the world is meritocratic imposes a crushing burden of responsibility on us for our defeats.

Understanding the sorrows of work will not magically remove them, but it at least spares us the burden of feeling that we must be uniquely stupid and clumsy for suffering them.

Specialisation

One of the greatest sorrows of work stems from a sense that only a small portion of our talents has been taken up and engaged by the job we have signed up to do every day. We are likely to be so much more than our labour allows us to be. The title on our business card is only one of thousands of titles we theoretically possess.

In his Song of Myself, published in 1855, the American poet Walt Whitman (18191892) gave our multiplicity memorable expression: I am large, I contain multitudes by which he meant that there are many interesting, attractive and viable versions of oneself, many good ways one could potentially live and work, and yet very few of these are ever properly played out in the course of the single life we have. No wonder that we are quietly and painfully conscious of our unfulfilled destinies, and at times recognise, with a legitimate sense of agony, that we could have been something and someone else.

The major economic reason why we cannot explore our potential as we might is that it is much more productive for us not to do so. In The Wealth of Nations, published in 1776, the Scottish economist and philosopher Adam Smith (17231790) first explained how what he termed the division of labour was at the heart of the increased productivity of capitalism. Smith zeroed in on the dazzling efficiency that could be achieved in pin manufacturing, if everyone focused on one narrow task (and stopped, as it were, exploring their Whitman-esque multitudes):

One man draws out the wire, another straights it, a third cuts it, a fourth points it, a fifth grinds it at the top for receiving the head; to make the head requires two or three distinct operations; to put it on is a peculiar business, to whiten the pins is another; it is even a trade by itself to put them into the paper; and the important business of making a pin is, in this manner, divided into about eighteen distinct operations, all performed by distinct hands. I have seen a small manufactory where they could make upwards of forty-eight thousand pins in a day. But if they had all wrought separately and independently, and without any of them having been educated to this peculiar business, they could have made perhaps not one pin in a day.

Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, Book 1, Chapter 1, Of the Division of Labour (1776)

Adam Smith was astonishingly prescient. Doing one job, preferably for most of ones life, makes perfect economic sense. It is a tribute to the world that Smith foresaw and helped to bring into being that we have ended up doing such specific jobs, and carry titles like Senior Packaging & Branding Designer, Intake and Triage Clinician, Research Centre Manager, Risk and Internal Audit Controller, and Transport Policy Consultant. We have become tiny, relatively wealthy cogs in giant, efficient machines. And yet, in our quiet moments, we reverberate with private longings to give our multitudinous selves expression.

One of Adam Smiths most intelligent and penetrating readers was the German economist Karl Marx (1818 1883). Marx agreed entirely with Smiths analysis; specialisation had indeed transformed the world and possessed a revolutionary power to enrich individuals and nations. But where he differed from Smith was in his assessment of how desirable this development might be. We would certainly make ourselves wealthier by specialising, but as Marx pointed out with passion we would also dull our lives and cauterise our talents. In describing his utopian communist society, Marx placed enormous emphasis on the idea of everyone having many different jobs. There were to be no specialists here. In a pointed dig at Smith, Marx wrote:

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Sorrows of Work»

Look at similar books to The Sorrows of Work. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Sorrows of Work and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.