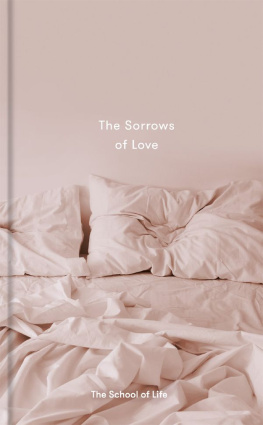

The Sorrows of Love

Other books in this series:

Why You Will Marry the Wrong Person

On Confidence

How to Find Love

Why We Hate Cheap Things

Self-Knowledge

The Sorrows of Work

The Sorrows of Love

The School of Life

Published in 2017 by The School of Life

70 Marchmont Street, London WC1N 1AB

Copyright The School of Life 2017

Designed and typeset by Marcia Mihotich

Printed in Latvia by Livonia Print

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not be resold, lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without express prior consent of the publisher.

A proportion of this book has appeared online at thebookoflife.org

Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders of the material reproduced in this book. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publisher will be pleased to make restitution at the earliest opportunity.

The School of Life offers programmes, publications and services to assist modern individuals in their quest to live more engaged and meaningful lives. Weve also developed a collection of content-rich, design-led retail products to promote useful insights and ideas from culture.

www.theschooloflife.com

ISBN 978-0-9957535-2-5

Contents

I

Introduction

II

The Sorrows

III

Conclusion: Stay or Leave?

I

Introduction

We expect love to be the source of our greatest joys. But, in practice, it is one of the most reliable routes to misery. Few forms of suffering are ever as intense as those we experience in relationships. Viewed from outside, love could be mistaken for a practice focused almost entirely on the generation of despair.

We should try to understand our sorrows. Understanding does not magically remove problems, but it sets them in context, reduces our sense of isolation and persecution, and helps us to accept that certain griefs are highly normal. The purpose of this essay is to help us develop an emotional skill that we term Romantic Realism. This can be defined as a correct awareness of what can legitimately be expected of love and the reasons why we will, for large stretches of our lives, be disappointed by it, for no especially sinister or personal reasons.

The problems begin because, despite all the statistics, we are inveterate optimists about how love should go. No amount of information seems able to shake us from our faith in love. A thousand divorces pass our doors; none seem relevant to us.

We see relationship difficulties unfold around us all the time, yet we still retain a remarkable capacity to discount negative information. Despite the evidence of failures and loneliness, we cling to some highly ambitious ideas of what relationships should be like even if we have never seen such unions in real life.

The ideal relationship is the equivalent of the snow leopard; our loyalty to it as a realistic possibility cannot be based on the evidence of our own experience. Instead it derives from a range of reckless ideas circulating in our societies about what sharing a life with another person might be like. The problem starts with the wedding. In a wiser world than our own, our marriage vows would set the tone from the outset.

A wedding day signals a commitment by two deeply imperfect people to endure a range of arduous difficulties until the end. It is a vow to be pretty unhappy together for much of the time without blaming one another unfairly. The family and friends gathered will be aware of their own relationship sufferings, will admire the couples courage and wish them luck while worrying (and knowing) that a rocky and in many ways, devastating experience lies ahead of the couple.

How happy we are depends to a large extent on whether we judge certain problems to be normal or not. Because our societies have failed to normalise and speak honestly about a great many issues in love, it is easy to believe ourselves uniquely cursed. We not only feel unhappy; we feel unhappy that we are unhappy. When difficulties strike, we start to feel that we are going out with a particularly cretinous human. The sadness must be someones fault; naturally enough, we conclude that the blame lies with our partner. We avoid the far truer and gentler conclusion: that we are trying to do something very difficult at which almost no one succeeds completely. At an extreme, we exit the relationship too early. Rather than adjust our ideas of what relationships are generally like, we shift our hopes to new people who wont share the irritating problems we experienced with the last partner. We blame our lover in order not to blame love itself, the truer but more elusive target.

We would be wiser to follow Romantic Realism in trusting that love will prove challenging for us, not for accidental or unique reasons, but for structural and intractable ones. Paradoxically, Romantic Realism is not the enemy of love; it is one of the attitudes that best contributes to the flourishing and survival of relationships in the long term.

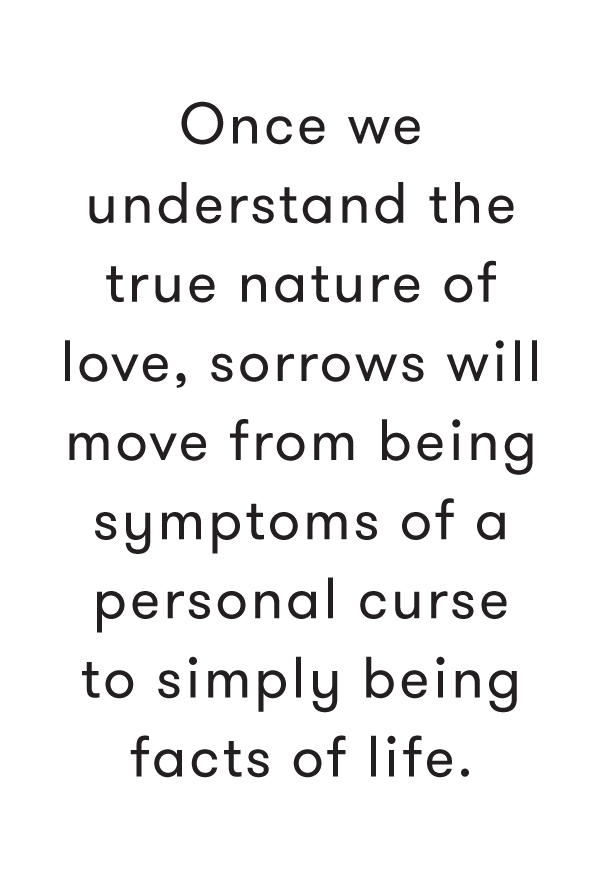

Once we understand the true nature of love, sorrows will move from being symptoms of a personal curse to simply being facts of life. Realising this will already bring significant and consoling progress, which this book hopes to hasten and develop.

II

The Sorrows

1

Ive become a monster

The Romantic ideal states that we will be nicer to our partner than to anyone else in the world. We selected them because we liked them so much and will therefore bring our kindest and most gentle sides forward in the relationship. Well be a lot nicer with them than with any of our friends, for example. We like the latter; we love the former.

But the reality is intriguingly and soberingly different. If things go to plan, we tend to become something akin to monsters in love. As Romantic Realism attests, we are likely to be significantly less kind to our partner than to almost any other human on the planet.

What explains our bad behaviour? Firstly, there is so much at stake. Our whole life is on the line. Friends are with us just for the evening; our mutual challenges may go no further than the need to locate a half-decent restaurant. But if things go well, the person we love becomes involved in some of the grandest and most complex matters we ever undertake: we ask them to be our lover, our best friend, our confidant, our nurse, our financial advisor, our chauffeur, our co-educator, our social partner and our sex mate. With them, we set up a house, raise a child, run the family finances, nurse our elderly parents, manage our careers, go on holiday and explore our sexuality. The job description is so long and so demanding, no one in the standard employment market could conceivably deliver on even a fraction of the demands. The good lover needs to be a blend of therapist, PA, teacher, host, chef, nurse and escort. Asking someone to marry us turns out to be an impossibly demanding and therefore pretty mean thing to suggest to anyone we really want the best for.

Furthermore, it is the precondition of any long-term relationship that we cannot easily fire the partner and flee when issues arise. Many frustrating situations are rendered a great deal more bearable with the thought that we can escape them without too many penalties. But within long-term love, an irritant that exists now may have to be endured for many decades. A problem that would not have to be maddening in itself (a towel on the floor, a delay in answering, a chewing sound) can unleash catastrophic anxiety when we feel that this may be a more or less permanent feature of the one life we have been granted on this earth. At the backs of our minds, driving our agitation during domestic struggles, is a simple, explosive thought: that the other person hasnt just done this or that thing that we find problematic; rather, they have ruined our lives.