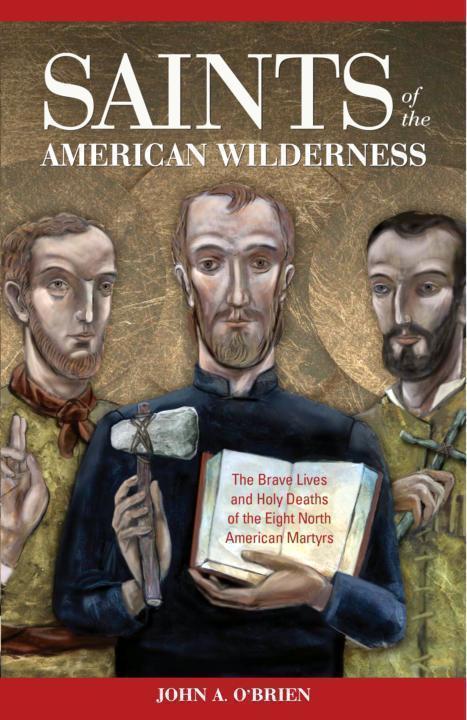

The Brave Lives and Holy Deaths of the Eight North American Martyrs

.............................. vii

Book One

........................... 3

Book Two

Isaac jogues

Rene Goupil

............................ 19

Book Three

Jean de Brebeuf

........................... 91

Book Four

........................... 171

Book Five

Charles Garnier

........................... 197

Book Six

.......................... 239

The chief sources of our knowledge of the life, customs, and languages of the Indians, and of the works and lives of the missionaries, colonists, traders, and others who entered upon the stage of New France from 1610 to 1672, are the letters and reports that the Jesuit missionaries sent to their superiors in France and Rome.

These letters and reports were published in a series of seventythree volumes under the title The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents, which have won unstinted praise from scholars throughout the world as a monumental contribution to American historical scholarship.

The writers were highly educated men, acute observers, conscientious recorders of what they saw and did. Leaving the most civilized country in Europe, these Frenchmen plunged into the unknown American wilderness and came face-to-face with the American Indian, whom they often found to be of the utmost ferocity.

To achieve the spiritual conquest of the Indian, in all his various nations, tribes, and dialects, the missionaries had first to attain thorough knowledge of his languages, customs, and ceremonies, to penetrate into his strange cults, and to secure insight into his habits of thought and action. The missionaries were the first students of the American Indian, and they had the best possible opportunity for pursuing their study, since they lived in his wigwams and traveled with him on long journeys through the wilderness and upon the myriad lakes and rivers.

The missionaries had attended the best colleges and universities in France. They were versed in the sacred sciences and in many branches of secular knowledge. They were able to make astronomical and meteorological observations, to chart maps, and to note what was peculiar in forestry, vegetation, and animal life. They were shrewd observers of racial characteristics, and one of them, Joseph Francois Lafitau, is recognized as the founder of modern technology.

They studied the Indian languages as missionaries eager to converse in them, and as philologists. Brebeuf's pioneer studies of the Huron and Petun languages laid the foundation for most subsequent work in these tongues. And Pierre Potier's seven books on the Huron language have proved so valuable that the Ontario government published them in 1920 at public expense.

Many of the missionaries' letters were written in Indian huts and wigwams and at campfires, amid a chaos of distractions: dogs barking, mosquitoes swarming over face and hands, smoke covering the missionaries like a pall, and dogs and children crawling over them alternately. Frequently the writers were suffering from fatigue and hunger, from sickness, or from wounds inflicted by rude hosts who, at the twinkling of an eye, could change into jailers and tormentors upon the whisper of a medicine man or sorcerer.

The style of the letters is nearly always simple and direct, informal and factual. The narrators indulge in no self-glorification or self-pity; they do not dwell needlessly upon the details of their own hardships, but rather set forth the facts with candor and objectivity.

With these letters begins the written history of the north: the valleys of the St. Lawrence, the Great Lakes, and the Mississippi. A few of the French traders - the coureurs de bois - had preceded the missionaries in some solitary places, but they seldom made records. Yet, when they came to the chapels to receive the sacraments after their long roaming, they would impart to the missionaries their experiences, which were reflected in the letters to France.

Considering the difficulties, it is a wonder that anything at all was written and dispatched. Jogues wrote some of his letters with a hand on which there remained but one whole finger; blood from a wound stained the paper. Gunpowder was his ink; the earth, his table. Many of the Indians regarded writing as magic and feared that it might do harm to them. Chaumonot, one of the chroniclers, at times had to write in secluded places and carry his letters in his clothing, because of the superstitious fear with which the Indians sometimes regarded them.

George Bancroft writes, "The history of the Jesuit Mission is connected with the origin of every celebrated town in the annals

When the letters that constituted the Relations were published in France, they stirred up enormous interest. They inspired the support of people, king, and aristocracy and encouraged many thousands of adventurous immigrants to cast their lot with the New World. Hence, the Relations not only record the history of New France, but they also had much to do with the making of that history.

The present volume incorporates the results of modern historical research, but the story it tells will be essentially the same as told by the missionary pioneers themselves in their letters from Indian campfire, wigwam, and canoe. It will capture the highlights of the seventy-three volumes of The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents.

Playing the central roles in the powerful missionary drama of New France were eight Jesuits who died as martyrs for the Christian Faith. They were the first in North America to be canonized as saints by the Catholic Church. Six of the eight were priests: Isaac Jogues, jean de Brebeuf, Gabriel Lalemant, Antoine Daniel, Charles Garnier, and Noel Chabanel; two were lay assistants: Rene Goupil and Jean Lalande. The eight are commonly known as the Jesuit Martyrs of North America.

This volume tells the story of their adventures, their apostolic labors among the Indians, and their heroic deaths at the hands of those to whose evangelization they had dedicated their lives. Their story is, in miniature, the story of the whole missionary enterprise of the first half of the seventeenth century, an undertaking that sought to win for Christianity and for civilization the whole Indian population of New France and ultimately of all North America.

There were many other missionaries, of the Society of Jesus and other orders. Their dedication to the work of conversion was heroic, ending often in martyrdom. They, too, endured hardship and suffering with patience and even with joy. They have a just claim upon our esteem and gratitude. It is with no disparagement of their magnificent achievements that we confine our story largely to the eight canonized Jesuits, who shall stand as the symbols of all the North American missionaries. In honoring these, we honor all.