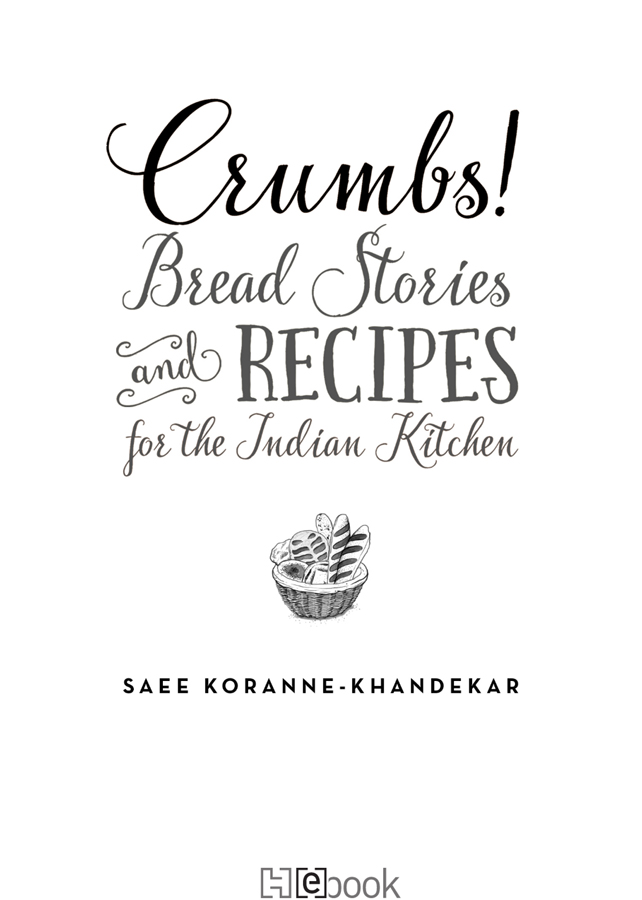

First published in 2016 by Hachette India

(Registered name: Hachette Book Publishing India Pvt. Ltd)

An Hachette UK company

www.hachetteindia.com

This ebook published in 2016

Copyright 2016 Saee Koranne-Khandekar

Saee Koranne-Khandekar asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved. No part of the publication may be copied, reproduced, downloaded, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover or digital format other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Print edition ISBN 978-93-5009-906-3

Ebook edition ISBN 978-93-5009-907-0

All views, ideas and opinions expressed and all statements of fact are as reported by them. The publishers are not in any way liable for the same.

Illustrations by Kruttika Susarla and Bhavi Mehta

Book design by Bhavi Mehta

Hachette Book Publishing India Pvt. Ltd 4th & 5th Floors, Corporate Centre

Plot No. 94, Sector 44, Gurgaon 122003, India

Front and back cover photos by Saee Koranne-Khandekar

Cover design by Bhavi Mehta

Originally Typeset in FF Scala 10/13.5

For my children, Avanee, Abheer and Ayaan

One reason to bake bread is to fill your kitchen with that aroma. Even if the bread turns out badly, the smell of it baking never fails to improve an hour or a mood. People trying to sell their homes are often advised to bake a loaf of bread before showing it. The underlying idea here is that freshly baked bread is the ultimate olfactory synecdoche for hominess. Which, when you think about it, is odd, since how many of us grew up in homes where bread was ever baked? Yet somehow that sense memory and its association with a happy domesticity endure.

Michael Pollan, Cooked

Contents

Introduction

My earliest memory of homemade bread is of Radha Kaku, my great-grand-aunt baking small, dense, chewy loaves in Amul processed-cheese tins, with their edges carefully filed and smoothened out. She would use everyday chapatti atta and commercial fresh yeast that she coaxed a local baker into selling her. The loaves were a far cry from the light, golden, perfectly square ones that we children drooled over as soon as they were unveiled by peeling back the branded, industrial wax-paper wrappers they came in.

In fact, as a child, I much preferred the white sliced bread that was so soft, it would feel almost insubstantial compared to the dense, moreish loaves baked at home. My brother and I just loved gorging ourselves on white sliced bread in every fathomable form. When it was fresh, we would slather our slices with Amul butter (once in a while, Amma my mother would sneak in home-churned white butter in the interest of our health, but we all know what goes best with bread, dont we, especially when were between five and fifteen?) and the deliciously gooey jams from the Womens India Trust (WIT) that Amma would lovingly splurge on for her kids. My maternal grandmother and great-grand-aunt would make the most mouth-watering gooseberry and tomato jams, guava jellies and murabbas traditional fruit preserves infused with sweet spices that we greedily heaped on the nearly weightless slices. When we ran out of fancy jams, we made do with the commercial wannabe jams, as my brother calls them. If not jams, then chutney pudi, (the familys favourite dry chutney made from roasted Bengal gram, dried chilies) is what we reached out for all through our childhood years. Even today, it continues to be in demand among us with its mildly spiced, curry-leaf accents punctuating every bite of salty buttered bread. Another old favourite were still addicted to was a scant pinch of Bhaskar Lavan Churna (an ayurvedic carminative that we treat like a spice mix, much like chaat masala) sprinkled on sliced and liberally buttered white bread, not because we could do with a release of a certain kind, but because the pairing is so shockingly playful on the palate that it deserves to be something of a legend.

Whatever the nature of the toppings, commercial bread didnt, necessarily, have to be fresh to sustain its appeal for us as children. As the loaf that had been purchased dried out in the fridge over the next few days, we would eat it, bit by bit, crisply toasted or soft-toasted (that is, first lavishly buttered and then roasted on a hot tava or griddle), richly piled with baked beans, sprinkled with something or the other for that extra zing, or alongside leftover bhaaji, ragda or similar legume. Like any good, middle-class family, we did full justice to the loaf at every stage of its shelf-life and seldom wasted a morsel.

On weekends and holidays, when we visited my grandparents in fancy South Mumbai, we would experience the added thrill of tasting bakery bread. This was long before the boulangeries came along; fancy breads were then available for a princely sum at five-star hotels. What ruled the city in those days, however, was the Irani or Muslim bakery.

Every other morning, a tall, bearded, tired-looking, lungi-clad man, a look-alike, or so it seemed to me, of Balraj Sahni as the Pathan in the film, Kabuliwala, would arrive at my grandmothers South Mumbai apartment, effortlessly balancing a huge aluminium trunk so stuffed with goodies that it could never be shut properly on his turbaned head. In one hand, the man carried a large jute bag, lined with paper; with the other, he would ring the doorbell.

Racing to the door from our I-dont-want-to-brush hideouts, we would stand and watch. Pray, rather. Pray that whoever answered the door would greet him with a nod of assent and open the outer door in welcome. And then, out of the mans jute bag would come temptingly soft, naked, unsliced loaves, teasing us with their golden glory, luring us with the sweet, warm smell of yeast. He would pull out a sparse wooden slicing board its centre having become concave from decades of use laid sideways in the bag and place it on the floor. Then he would take out a full or half loaf, depending on our requirement for the day, and rest it on the board. Next, a long, thin blade, that functioned like a knife, appeared, as if out of nowhere. Using quick, precise movements, the man would expertly section the loaf into thick slices that gently keeled over sideways in surrender. The slices were then held together, wrapped in newspaper and kept aside, while we made our other choices pao or kadak pao (brun) to dunk in our milk, khaari those ubiquitous rectangles of puff pastry for the adults to dunk in their coffee and delicious triangular sugar khaari for the kids to make milk palatable. Suddenly, the day would begin to look promising and the mornings purchase became the focal point of all activities planned for the next several hours.

This tradition of home-delivered bread from a bakery is dying not just in Mumbai, but all over the country. Even Goa, with its talented local bakeries that make fresh pao twice a day, is losing out, slowly but surely, to white commercial bread and supermarket competition. This is a trend I cant help but regard with dismay as I recall those days when fresh, unadulterated bread was an indispensable part of our lives. As far as we were concerned, fresh home-delivered bread wasnt just food; it was the source of excitement, of breathless anticipation, of desire kindled and satiated over and over again the very essence of our childhood, with all its promises just waiting to be fulfilled.