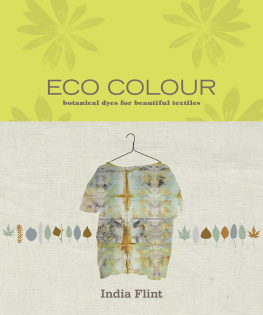

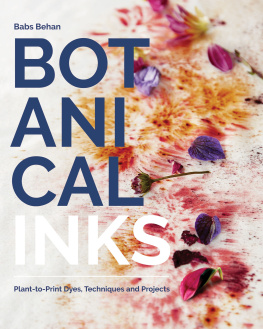

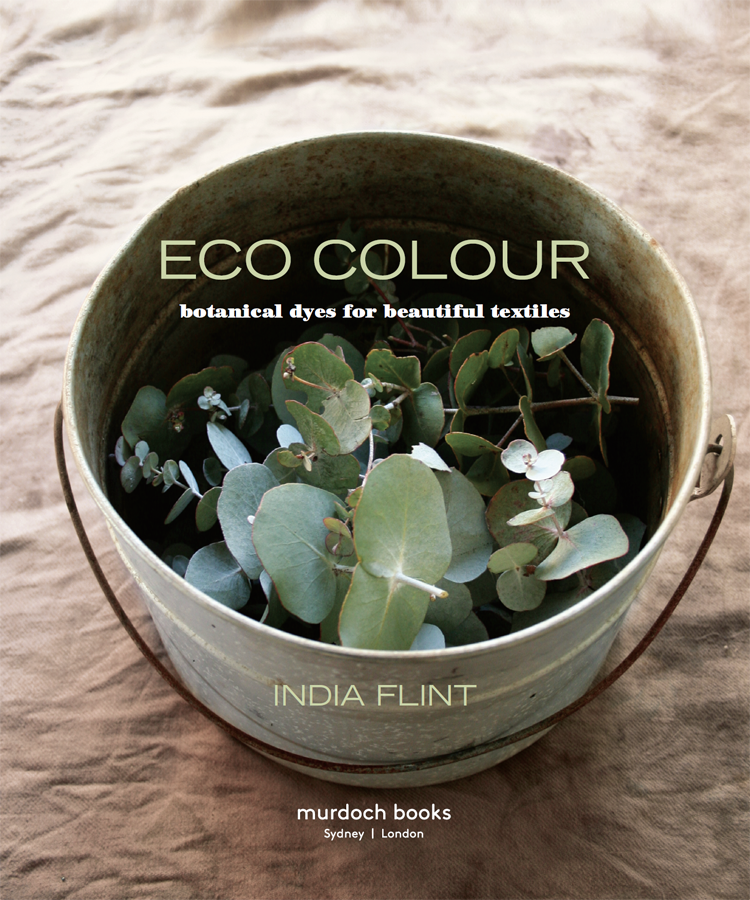

Internationally renowned dyer and artist India Flint draws on her years of experience and experimentation in natural dyeing techniques to present an expert, highly accessible and achievable handbook of ecologically sustainable plant dye methods using renewable resources, most of which can be found in the average home garden. Eco Colour is regarded by many as a textbook of sustainability and uses an exciting range of projects to demonstrate a variety of techniques, some of them processes developed by the author, including the now widely adopted ecoprint. Projects range from the simplest imaginable, such as solar dyeing in which the fabric and dye material are placed in a closed jar and left for a few weeks in a sunny spot to the positively romantic including dyeing with ice-flowers. The result is a boundless range of pure, gentle, natural colours produced with the least possible harm to the environment and the dyer.

India Flint is an artist and writer whose works are represented in collections and museums in Germany, Latvia and Australia. She lives on a farm in rural South Australia, researching plant dyes, making artworks and planting trees. Indias textile practice has embraced theatre, art and fashion and formerly also a range of salvage clothing under the label prophet of bloom. In 2018 she launched the School of Nomad Arts, offering online courses as a means of teaching a wider demographic while reducing her travel footprint on the planet. Indias work is featured on her website: indiaflint.net and through her Instagram profile @prophet_of_bloom.

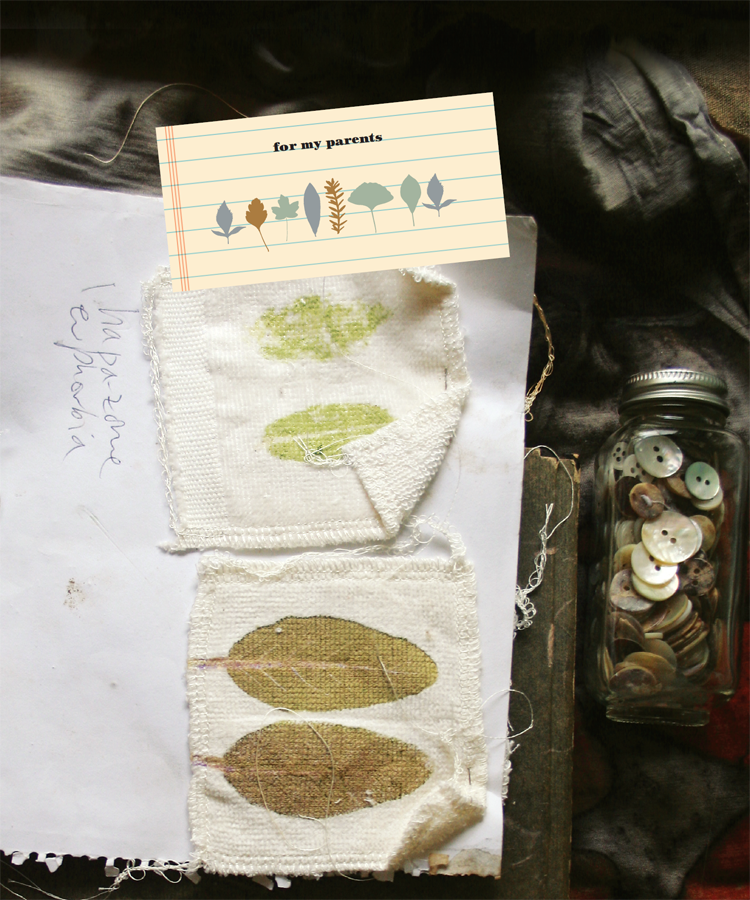

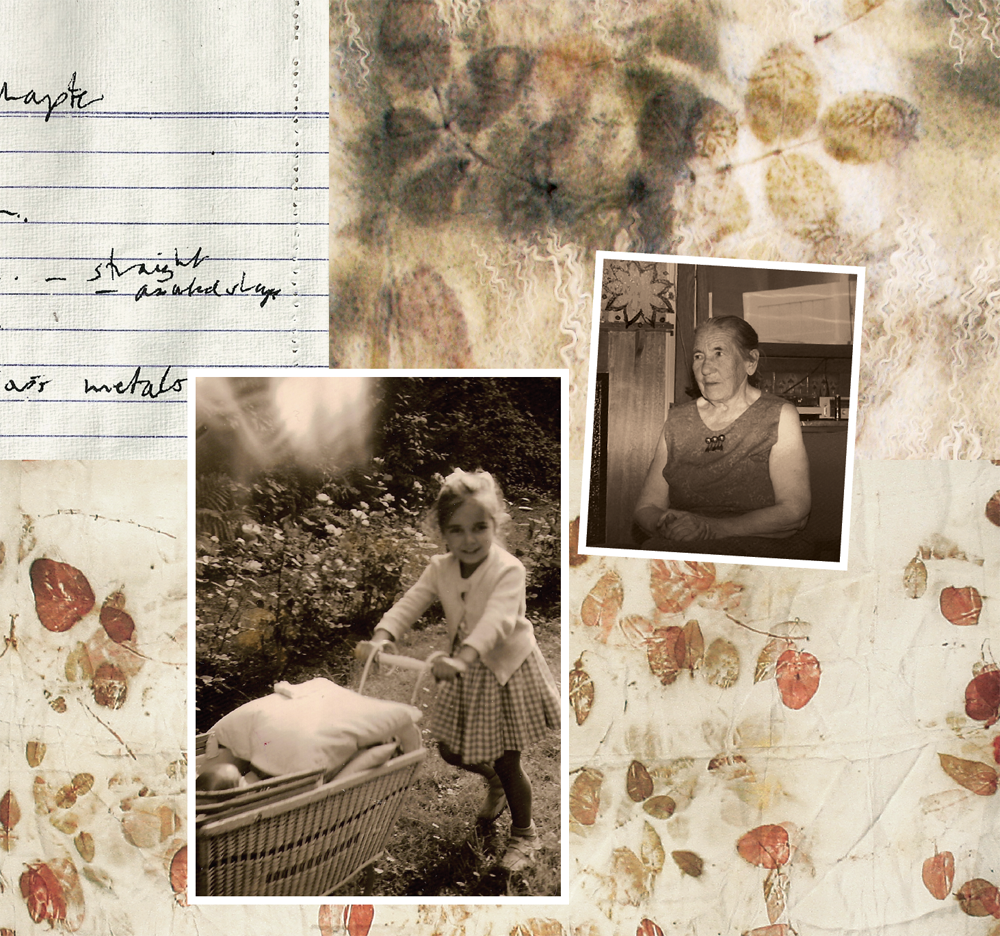

The author as a child. Above right: The authors grandmother, Bertha Pilskalns. Top right: Details of sommergarten faerie dress felted of wool, flax and silk, and printed with leaves from various Rosa , Philadelphus and Fragaria species.

PROLOGUE

When I was a very small child, I had the great good fortune to be cared for by my maternal grandmother while my mother pursued studies in art. Little did I realise how influential her guidance would prove and that I would eventually make a living using the simple techniques she taught me all those years ago.

Grandmother sewed all her clothes on an old portable hand-cranked Singer sewing machine, purchased in 1927 and lugged by her through war-torn Europe on the flight from Latvia in 1944. Using this machine, she made stylish clothing for her daughters from tattered rags during the famine years. Particularly memorable is a nightgown (sadly, later lost in a bushfire) fabricated from a linen sheet hand-woven by my great-grandmother from home-grown and home-spun flax. This was worn in succession by my aunt, my mother and eventually me. Later in Australia, the sturdy Singer was used to sew curtains and pillowcases for the little house she worked so hard to buy. The same sewing machine kept me sane many years later, when I was living on the outskirts of the Andamooka opal fields in the far north of South Australia, in a house independent of the power grid.

As well as growing vegetables and flowers, making jams and baking delicious bread, my grandmother also made (by hand) feather pillows for each of her grandchildren. This involved an arduous journey by public transport to the slaughter-house to collect the bloodied feathers. These were tied in a cloth bag, scalded and thoroughly rinsed and dried before Grandmother (sitting in a closed room with her long hair tied up in a duster) stuffed the feathers into the ticking cases and stitched them up firmly. That was more than forty years ago. I still lay my head to rest every night on the pillow I watched her sew. It makes for good dreams.

But withal it was the magic she created in the dye-pot that impressed me most. When her blouses and cardigans became faded with age, she would over-dye them with colours extracted from onion skins, or left-over tea or calendula flowers from the garden. While she would boil her cloth and add cooking salt as a mordant (not necessarily practices I will recommend in this book), the very idea of making colour from the garden was completely enchanting for me.

My mother, too, played a fundamental role in nurturing what would become my passion, as in addition to instructing me in the art of botanical observation and illustration, it was she who took charge of dyeing the eggs for the Easter celebrations every year. In the Latvian tradition, fresh hen eggs are wrapped in layers of plant material, beginning with tiny green strawberry leaves and other pretty herbs from the garden, and finishing with a good layer of dark brown onion skins. The bundled eggs are placed in a saucepan with water, brought to the boil, simmered for ten minutes and allowed to cool. Unwrapping each egg is always a delight as delicate patterns are revealed, each one unique. Experimenting with the egg-dyeing traditions using eucalyptus leaves on cloth led me to the discovery of the eco-print in 1999.

My father complemented this practical knowledge by instilling in me the love of wild nature, trees and forests. My first forest outing took place when I was only three weeks old, tucked into his old haversack (so I have been told) with a blanket and dozing happily as my parents climbed the Cathedral Range in Victoria.

As well as marvellous parents, I was also blessed with splendid great-aunts. Tante Ilse, a master bookbinder who lived near the Pilsensee in Bavaria, showed me the technique of making delicate leaf-prints to decorate the endpapers of books. Tante Rose was a passionate gardener who taught me the importance of binary nomenclature in plant identification, and Tante Milda made amazing wines and liqueurs from a wide array of berries, flowers and roots.

My paternal grandparents (mathematicians by profession) spent their weekends pottering about a small-holding in Vermont, harvesting edible plants from the wild and cultivating a complementary range of vegetables. Here I learned to keep a look out for black bears when gathering raspberries, and discovered for myself the staining properties of elderberries.

This book is thus a confluence of not one but several lifetimes experiences, and a distillation of many learned skills. The text is by no means exhaustive, nor is it intended to be prescriptive. Rather it should function as a guidebook to an ongoing and colourful journey of exploration through the flora of the world, and as a series of signposts to other sources of knowledge. It has been a very long time in the brewing.