ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

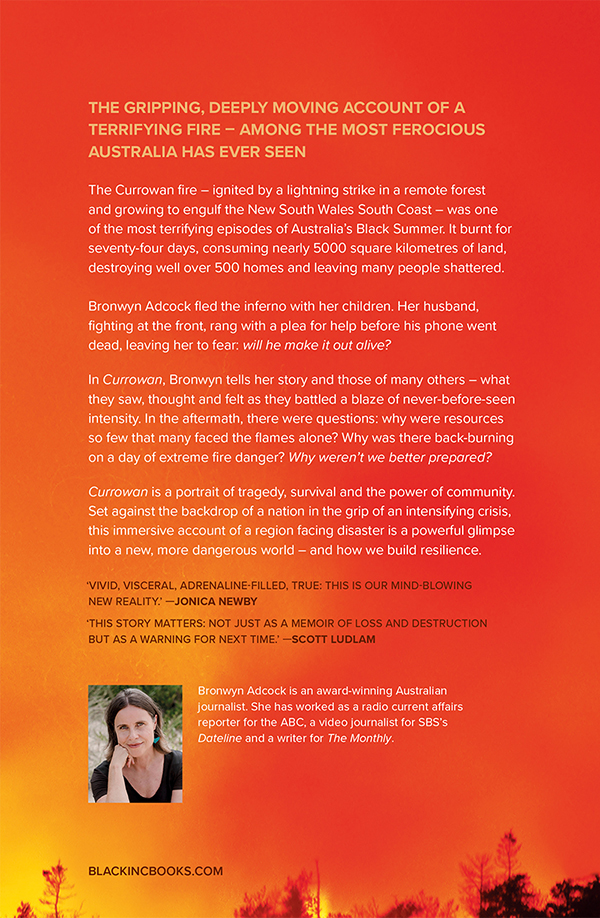

T HIS BOOK WOULD NOT HAVE BEEN POSSIBLE WITHOUT the many people on the South Coast who generously agreed to share their fire stories with me. Some, but not all, of these stories have been told within these pages, yet I am grateful to have heard every one. Being asked to recount experiences filled with trauma is hard, and I was fortunate to have so many people willing to go back down that road. In hearing these stories, I was consistently in awe of the bravery, quick thinking and fortitude that was displayed during the fires, and this remains a constant source of inspiration for me. All names used in this narrative are real, except in instances where individuals asked not to be identified.

To all my fellow travellers through the period of the fire: thank you. While everyone was facing stress and disruption of their own, I never had any shortage of support and friendship. The list is not exhaustive by any means, but thanks must go to my parents, for housing us at short notice and for constant support over the summer (and always); to Ben, for being a calm presence in my worst moment; and to Donovan, for arriving to help with the hard jobs. To all the members of our WhatsApp group, you were a lifeline (even with the rampant poor punctuation and bad spelling).

To the amazing Bawley crew of friends: you all came through, as always. Special thanks though to Mel for emergency plumbing assistance and events organising to keep our spirits buoyed; to Lisette and Flo Food Van for keeping us in coffee even as everything burned; and to Zora for caring for our wildlife. Colin, Lucille and Finn turning up with new bicycles (thank you, Trek) was a high point in a grim summer. And Naomi, your prepping skills saved the day while I was unravelling. Thank you to Jo for finding us somewhere to live. And enormous gratitude to Zane who helped build me a studio to write in even before he started rebuilding his own home.

I will be forever grateful to the Bawley RFS crew who came up to our property the night of the fire: Charlie, Dump, Luci, Joy and Lise. And David for helping get them there.

Thank you to Nick Feik at The Monthly, for guidance on transitioning from writing a story about others fire experiences to my own; to Varuna, the National Writers House, for the Writing Fire, Writing Drought fellowship; to ABC journalist Anna Henderson, for uncovering vital information through freedom of information; and to ABC journalist Sean Rubinsztein-Dunlop, for his work on the Conjola fire.

Thank you to Chris Feik and Julia Carlomagno at Black Inc. for envisaging this book, skilled eyes, encouragement and patience.

Most of all, though, thank you to Chris for saving our home and for supporting our family as I disappeared for long periods to write this book. And to my children, for being such troopers through it all.

Chapter 1

THE GATHERING STORM

T HE YEAR 2018 STARTS WITH A HEATWAVE, COMING down upon southeastern Australia. On the first Sunday, just after three in the afternoon, the temperature in the western Sydney suburb of Penrith slides up another notch, hitting 47.3 degrees Celsius making it officially the hottest place on Earth. Temperature readings are taken in the shade, though, and across the city at the Sydney Cricket Ground, where the final Ashes test is being slogged out, a heat-stress tracker on the sideline measures what anyone out in the sun is experiencing: it peaks at 57.6 degrees. Incredibly, just one player, the English captain, finishes the day in hospital. At an international tennis tournament at Sydney Olympic Park, the heat shuts down three courtside cameras. Further south in Victoria, it bubbles and melts bitumen on the Hume Highway, slowing holiday traffic to a crawl.

This blistering start proves just a prelude. Above-average temperatures continue throughout summer and into autumn. Another heatwave, this time stretching across the entire country, strikes for ten days in early April. Dozens of towns in New South Wales experience consecutive days above 35 degrees; the ninth day is the hottest Australian April day on record. The Bureau of Meteorology describes whats going on as abnormal.

The heat is not the only extreme weather event underway. The amount of rain falling across eastern Australia started diminishing from late 2016, and by 2018 decent rainfall is almost a complete stranger to the land. New South Wales has its driest autumn in more than a century. By winter, 100 per cent of the state is drought-declared.

This is supposed to be the year Greg Mullins finally starts relaxing. It is his first full year of retirement after a thirty-nine-year career with Fire and Rescue NSW. Hed served the last fourteen as commissioner, in charge of one of the largest urban fire and rescue services in the world the only man who stayed longer in this position died at his desk. But Mullins is watching the landscape whither under the extreme heat and drought, unable to escape a growing sense of unease that the conditions are being set for a catastrophic fire event.

Mullins knows as well as anyone that Australia has always been bushfire-prone. Growing up in the bushy outer suburbs of Sydney with a father who was a volunteer firefighter, he was schooled in the realities of helping his mum and siblings protect the family home when fires were nearby and Dad was out on the truck. He fought his first fire at age twelve, and countless more over the course of his professional life. But he fears that whats coming next is right off the scale of anything this country has ever seen.

For the past decade, hes been observing significant changes to the rhythms of fire that Australia has always known. No longer just a feature of summer, bushfires are appearing in other seasons, the big ones coming closer together, their behaviour more extreme. Mullins, like most professionals in the emergency services field around the globe, sees these shifts as harbingers. He knows the science says human-created climate change is making the planet hotter and drier, which in turn will make bushfires worse.

The warnings have been coming in for more than a decade, becoming stronger with time. In 2005, Australias national science agency, the CSIRO, said southeastern Australia would face an increased fire risk in the future. By 2008, a report commissioned for the Australian government put a date on it: Fire seasons will start earlier, end slightly later and generally be more intense. This effect increases over time, but should be directly observable by 2020. The following year, a government-funded research organisation warned our current knowledge and practices on bushfire management would not be adequate in this new era of climate changefuelled bushfires. In 2017, a major study examined historical records of fire weather in Australia going back sixty-seven years. Using the Forest Fire Danger Index the combining of meteorological data such as heat, wind and humidity, along with dryness, to come up with the degree of fire danger on any given day it revealed Australia was already experiencing more days of dangerous fire weather, with increases in the frequency and magnitude of the extremes.

By 2018, Australia has been warming at an accelerating rate since the 1950s, with each decade hotter than the one before, and cool season rainfall has been diminishing in southeastern Australia for twenty years: key ingredients for this more dangerous bushfire era to eventuate.

But it isnt simply fear of a bad fire season that is keeping Mullins from enjoying his retirement. His years on the inside, working closely with successive governments, have convinced him that those in power have failed to confront what is happening. As a result, we are not prepared for this new epoch.

Next page