Contents

Guide

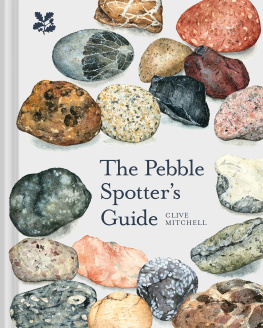

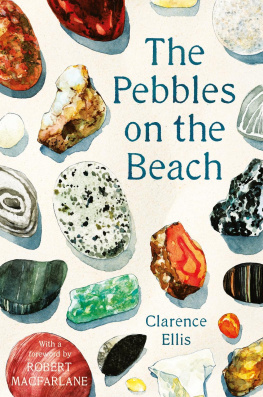

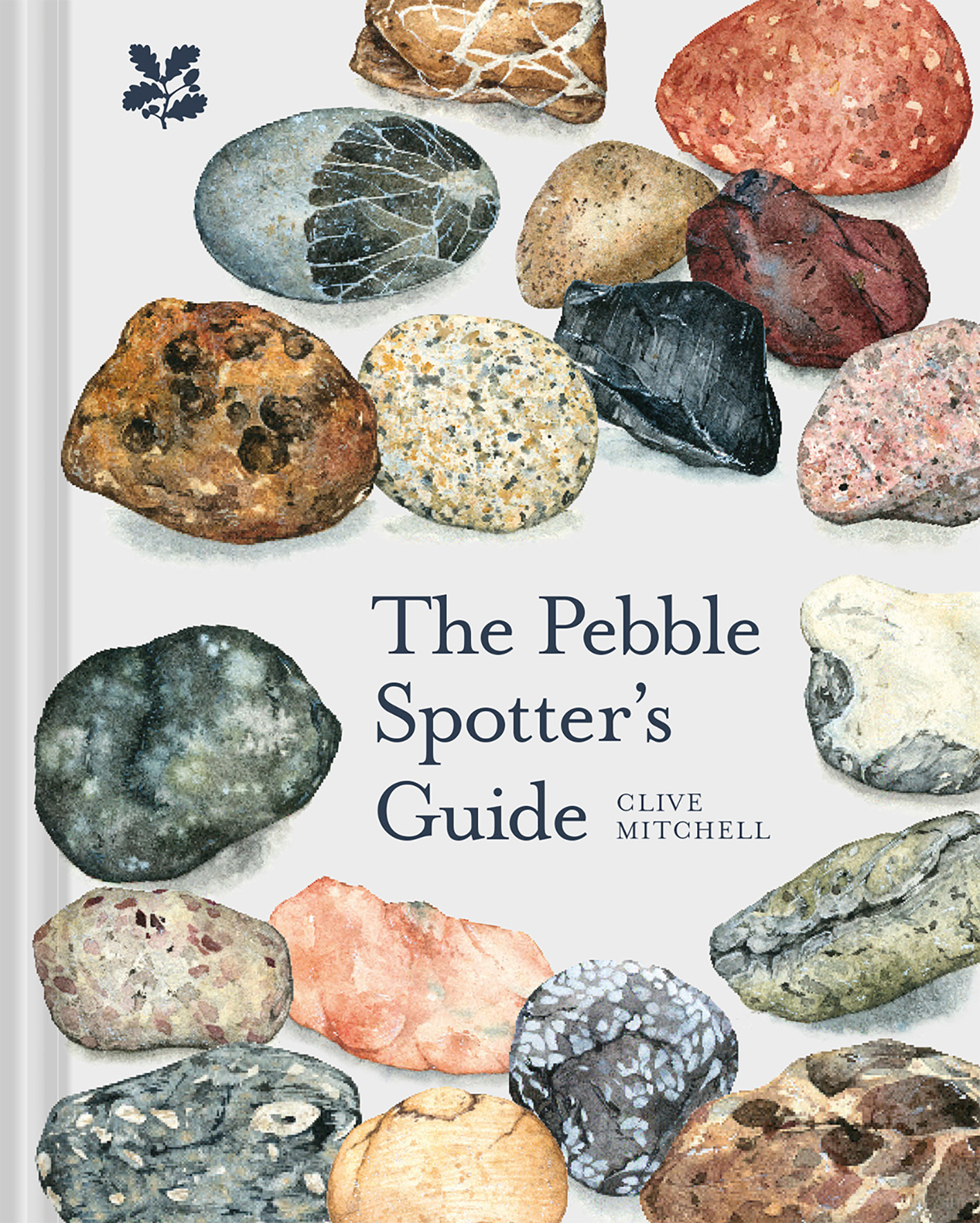

A ring of sandstone pebbles with veins of quartz.

I dedicate this book to my beautiful wife Joy.

We have shared many happy times on beaches, with the occasional pebble picked up along the way, and look forward to many more.

Contents

Introduction

They say that pebble-hunting is what geologists do on holiday, and my first experience of geology was over 50 years ago, picking up pebbles on the beaches of Cornwall and Devon on family holidays. I had no idea what they were. It was purely the tactile pleasure of holding a perfectly smooth pebble that fitted neatly into the palm of my hand. So while a more technical definition of a pebble is any rock between 4 and 64mm ( 3 / 16 2 1 / 2 in) in diameter, mine is simply:

A pebble is a smooth rock that fits

neatly into the palm of your hand.

This of course means that pebbles will range in size depending on how large your hands are and that is part of the point the pleasure of a pebble is personal. The best pebbles are always the ones that you find yourself, that appeal to your own preferences for colour, texture and shape, and slip into your hand as if they were designed just for you.

As a professional geologist I like to know what my pebbles are made of, and I can usually work it out on the spot. For the non-geologist this will be a little harder as rocks just look like, well, rocks. Pebbles are usually, but not always, formed from a naturally occurring rock that has been worn smooth by the action of water on beaches, or in lakes and rivers. There are also pebbles formed from artificial materials such as concrete, brick and glass; while these are not rocks, they often make interesting pebbles that are sometimes hard to distinguish from rocks. Older forms of concrete can often look like a pebbly sandstone.

A few basics to set the scene, geologically speaking. I have been referring to pebbles as rocks. You might have been calling them stones, but this technically only refers to rocks that have stone in their name such as limestone, sandstone, gritstone, siltstone and mudstone. If you start using the word rocks instead of stones, youll be in my good books.

Gneiss

Naturally occurring rocks fall into three categories:

Igneous:these are rocks that have formed from molten magma, ranging from those created by volcanic eruptions, such as basalt and andesite, to those with large crystals formed by slow cooling underground, such as granite and gabbro.

Sedimentary:these are rocks formed by the processes of weathering, erosion and deposition, including sandstone, siltstone and mudstone, or made from the remains of past life, such as chalk and other forms of limestone.

Metamorphic:these are rocks formed when other rocks are changed by intense heat or pressure, or a combination of both. So mudstone is squashed into slate and ultimately the minerals are recrystallised to form schist. Limestone becomes marble, with all evidence of past life gradually removed. Granite takes on a whole new appearance when the minerals it contains, such as quartz, feldspar and mica, are reshaped into the swirling layers of gneiss.

Rocks are made of minerals. Identifying these minerals is the first step in working out what a rock is. This is easy when the minerals form the lovely large crystals that you often see in granite. But many rocks are made of very small mineral grains or crystals that are often impossible to see without a magnifying glass or microscope. But dont despair even professional geologists struggle to identify these without a laboratory. Other aspects of rocks used in their identification include colour, the size of the mineral grains or crystals, and the layers and other textures.

To help you in your quest to identify your pebble there are many good guidebooks on rocks and minerals (see the recommended list at the end of this guide). One of my favourite methods is to find a pictorial guide and compare the images with what Ive found it works for me!