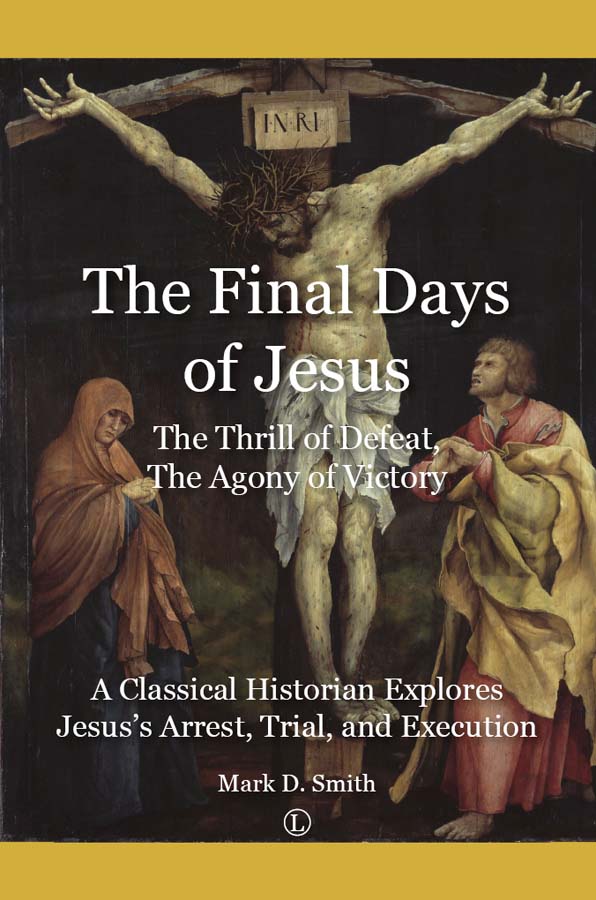

The Final Days of Jesus

Detailing the final days of Jesuss life on earth is a theological, literary, archaeological, historical and geographical conundrum which requires many different interpretive skills to understand what really happened and how we know what we think we know about those final days. Many recent authors have tried to write about these moments that are so significant for many around the world. Mark D. Smiths training in the material culture and in the study of the classical world makes The Final Days of Jesus: The Thrill of Defeat, The Agony of Victory the closest to giving us a full rendering of what happened and why.

Professor Richard Freund,

Maurice Greenberg Professor of Jewish History and

Director of the Maurice Greenberg Center for Judaic Studies

at the University of Hartford

Mark Smith has brought vividly to life the politics that swirled around the arrest and trial of Jesus. Using insight and the latest archaeological findings, Smith explores the inter-dependence of the Roman governor Pilate and the house of the high priest Caiaphas, calling into question the standard narrative of Jesuss trial before the Sanhedrin. A thoughtful perspective, from which readers of all faiths will benefit.

H.A. Drake,

author of A Century of Miracles

The Final Days of Jesus

The Thrill of Defeat,

The Agony of Victory

A Classical Historian Explores Jesuss

Arrest, Trial, and Execution

Mark D. Smith

The Lutterworth Press

The Lutterworth Press

P.O. Box 60

Cambridge

CB1 2NT

United Kingdom

www.lutterworth.com

publishing@lutterworth.com

ISBN: 978 0 7188 9510 5

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A record is available from the British Library

Copyright Mark D. Smith, 2018

First Published, 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this edition may be reproduced,

stored electronically or in any retrieval system, or transmitted

in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without

prior written permission from the Publisher

(permissions@lutterworth.com).

For Debi:

My partner, my comfort, my mirror,

My most incisive critic,

My best friend,

My lover,

My wife.

Contents

Illustrations

Tables

This book finds its genesis in three formative encounters. The first was a graduate course I took from an orthodox rabbi on Judaism in the time of Jesus. That course not only painted a fuller and more nuanced portrait of the period than I had ever considered, but it also provided me with a thoughtful encounter with the Sanhedrin, especially the many ways in which its behaviour in the New Testament accounts of the trials of Jesus was inconsistent with Jewish law. That course also helped to sensitise me to the long and terrible history of Christian anti-Semitism that has grown out of the claim that the Jews were responsible for killing Jesus. The rabbi doubtless said many more sophisticated things than I can remember, for it was a long time ago, but he gave me the profound gift of a stubborn and fertile question.

The second was my initial encounter with the Jesus Seminar. Many years ago, I attended the lectures of a colleague, a New Testament scholar and affiliate of the Jesus Seminar, who was teaching a course on the historical Jesus. His required readings included Marcus Borg, John Dominic Crossan, and E.P. Sanders, among others. It was there that I first encountered seriously the so-called Third Quest for the historical Jesus. I also learned of its advances over the first two quests, many of which seemed quite sensible, such as paying attention to historical evidence beyond the pages of the New Testament and thinking carefully about ones methodology for evaluating evidence. Under my colleagues tutelage, I came to grapple with the Seminars procedures, assumptions, criteria, and provocative conclusions. In particular, I was struck by Crossans argument that it is unlikely that Jesus was ever buried after the Romans crucified him, for, he asserted, denial of burial was part of the standard punishment the Romans meted out to those they executed. As a Roman historian, I could understand where he got these ideas, but I also wondered what a careful scrutiny of the evidence for Roman executions might reveal. On the whole, I was impressed, but I was struck also by a niggling sense of disconnect between the study of the historical Jesus and the study of other historical subjects in the ancient world.

It took the better part of two decades for me to find the opportunity to connect the dots between these two encounters. I began by studying capital punishment in the Roman Empire, which led ineluctably to that most infamous of Roman executions, and backwards from there to the rest of the research that forms the foundation of this book.

The third encounter will explain the subtitle. When I was young, my family had a weekly ritual: we would gather round the television to watch ABCs Wide World of Sports. Every Saturday afternoon, the inimitable voice of Jim McKay greeted us: Spanning the globe to bring you the constant variety of sport, the thrill of victory, the agony of defeat . Those words and the accompanying music always raised the heartrate. I cant remember the pictures associated with the thrill of victory, but Ill never forget the agony of defeat: an ill-starred ski jumper, falling off the side of the ramp and bouncing like a rag doll down the icy slope. That ski jumper, I later learned, was Vinko Bogataj of Slovenia. He was actually quite a good jumper, except on March 21, 1970 when he suffered that terrible accident. Little did he know that he was destined to repeat that feat every Saturday afternoon for the next twenty-eight years. As an athlete and a student of history, Ive thought a good deal about the thrill of victory and the agony of defeat but the story of the final days of Jesus seems to invert the premise, showing us instead the thrill of defeat, and the agony of victory.

______________________

In principio are the first words of Genesis and the Gospel of John in the Latin Vulgate translation: In the beginning.

I owe this phrasing to Dr Timothy Weber.

I

Historia:

As the sun sank into the mare nostrum, as the Romans called the Mediterranean Sea, 14 Nissan on the Hebrew calendar had arrived. It was the beginning of the much-anticipated Passover feast of the year AD 33. While it is the Passover celebration, ritual, and meal that makes this night different from all other nights of the year, the Passover of AD 33 differed from all other Passovers. On this Passover, the inexorable current of history had drawn together three individuals in Jerusalem who, in a single day, would change the course of Western civilisation.

One of the individuals was a minor Roman who by dint of family connections and military service had risen to become the marginally competent governor of an obscure Roman province: Judaea. Were it not for the events of that Passover, the name Pontius Pilatus would probably be known only among a handful of specialised scholars. The second individual was a self-made man from a minor priestly family who had risen to the position of high priest of Israel from AD 6 to 15. His family connections, dedication, and rare knack for diplomacy had brought his family to wealth and prominence. His name was Chanin ben Seth, better known in the New Testament as Annas. The third individual was an obscure itinerant Jewish teacher from the tiny Galilean village of Nazareth, far removed from the urban bustle of Jerusalem. As a pilgrim, he too had come to the Holy City for this night unlike all other nights. His name, in the Hebrew of the time, was Yeshu ha-Notsri or Yeshua ben Yoseph, Jesus of Nazareth or Jesus son of Joseph, who was a builder by trade.