Revenge and Gender in Classical, Medieval and Renaissance Literature

Revenge and Gender in Classical, Medieval and Renaissance Literature

Edited by Lesel Dawson and Fiona McHardy

Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com

editorial matter and organisation Lesel Dawson and Fiona McHardy, 2018

the chapters their several authors, 2018

Edinburgh University Press Ltd

The Tun Holyrood Road, 12(2f) Jacksons Entry, Edinburgh EH8 8PJ

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 4744 1411 1

The right of Lesel Dawson and Fiona McHardy to be identified as the editors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498).

Contents

Introduction: Female Fury and the Masculine Spirit of Vengeance

Lesel Dawson

1 Why are the Erinyes Female? or, What is so Feminine about Revenge?

Edith Hall

2 Re-marking Revenge in Early Modern Drama

Alison Findlay

4 Now I am Medea: Gender, Identity and the Birth of Revenge in Senecas Medea

Kathrin Winter

5 The Avenging Daughter in King Lear

Marguerite A. Tassi

6 Brother Unkind: Annabellas Heart in Tis Pity Shes a Whore

Sara Eaton

7 Cursing-Prayers and Female Vengeance in the Ancient Greek World

Lydia Matthews and Irene Salvo

8 The Power of our Mouths: Gossip as a Female Mode of Revenge

Fiona McHardy

9 Womens Weapons: Education and Female Revenge on the Early Modern Stage

Chloe Kathleen Preedy

10 The Vengeful Lioness in Greek Tragedy: A Posthumanist Perspective

Alessandra Abbattista

11 Shes Turned Fury: Women Transmogrified in Revenge Plays

Janet Clare

12 A Phrygian Tale of Love and Revenge: Oenone Paridi (Ovid Heroides 5)

Andreas N. Michalopoulos

13 Lament and Vengeance in the Alliterative Morte Arthure

Anne Baden-Daintree

14 Whats Hecuba to Shakespeare?

Tanya Pollard

15 Nursed in Blood: Masculinity and Grief in Marstons AntoniosRevenge

Rebecca Yearling

16 Outfacing Vengeance: Heroic Dying in Websters The Duchess ofMalfi and Fords The Broken Heart

Lesel Dawson

List of Figures

Acknowledgements and Dedication

Many of the essays in this volume were first given at the conference Female Fury and the Masculine Spirit of Vengeance which took place in 2012 at Bristol University. The conference was generously supported by: Bristols Institute for Research in the Humanities and Arts (BIRTHA); Bristols Institute of Greece, Rome and the Classical Tradition (IGRCT); the Department of English; The Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies; and the assistance of Samantha Barlow. Bristol Universitys Faculty Fund supported the project in its final stages. Mark Curtis, Tamsin Badcoe, Ian Burrows, Ian Calvert, Ros Powell, Laurence Publicover and Rebecca Yearling offered valuable support and advice. Gratitude is also due to Samantha Matthews, who was a vigilant reader during the final stages of the volume and a wonderful friend throughout.

This book is dedicated to Sara Eaton, who sadly died before the volume came to completion. Sara was an inspirational scholar and teacher and we are honoured to include her work in this collection.

Introduction:

Female Fury and the Masculine Spirit of Vengeance

Lesel Dawson

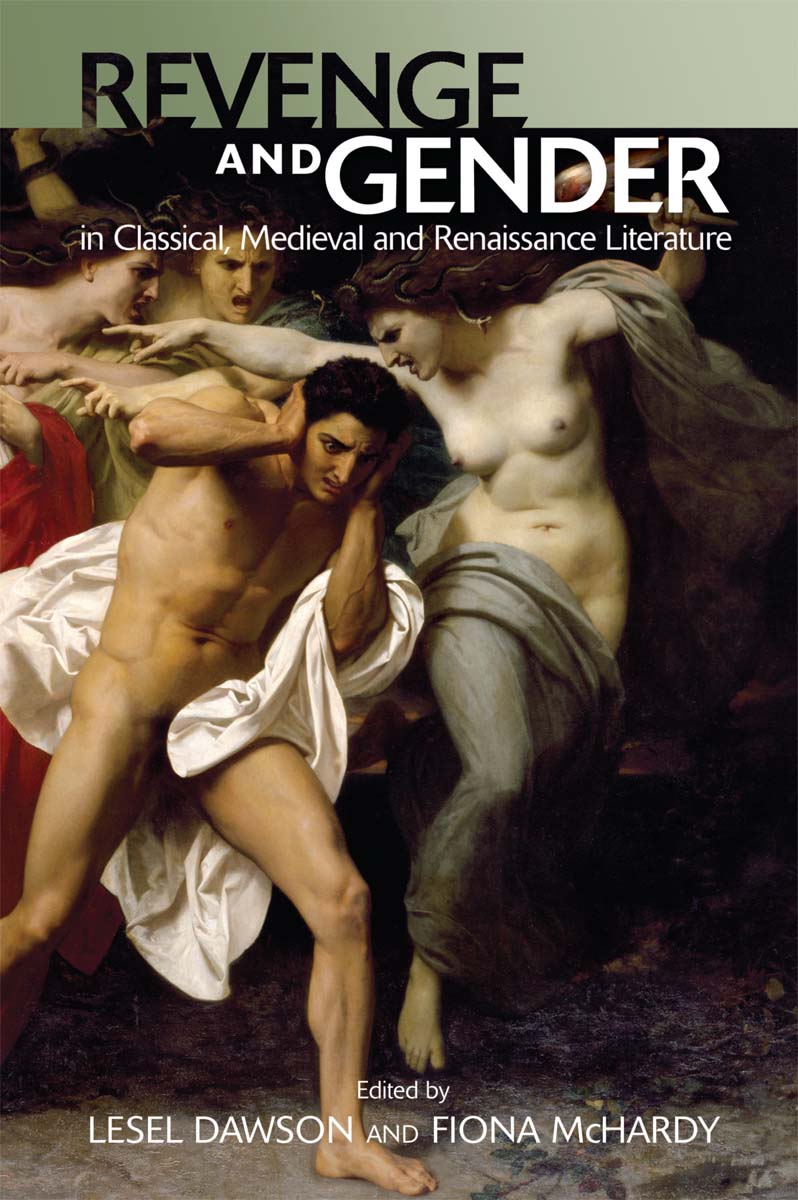

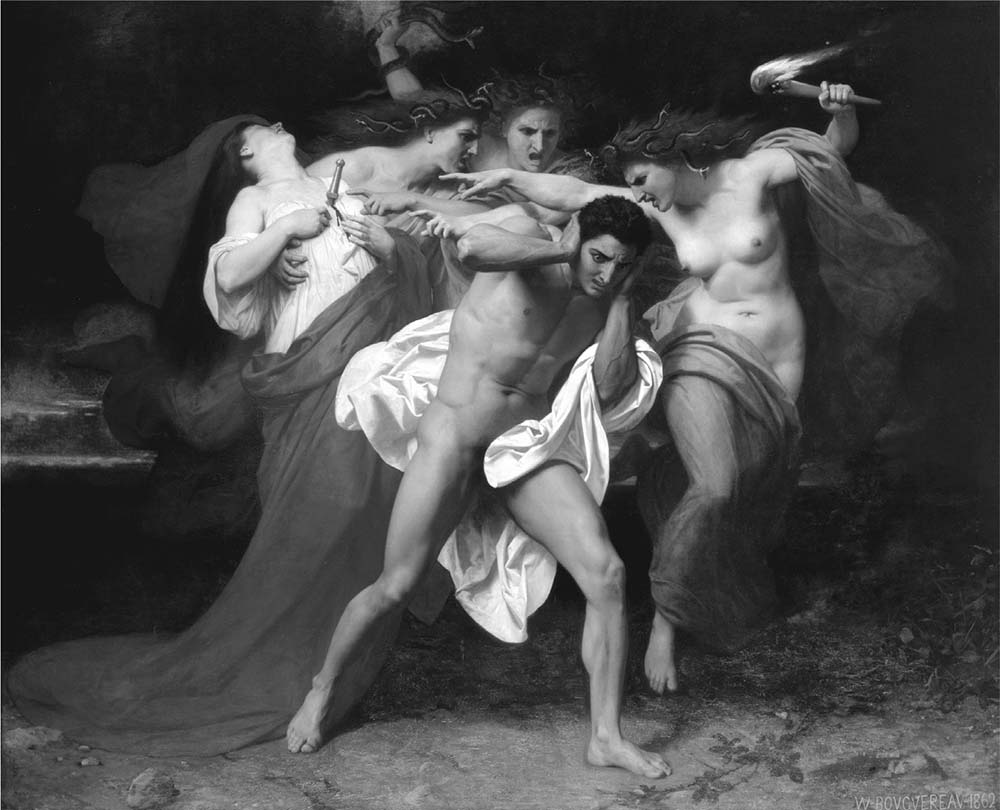

I n William Adolphe Bouguereaus Orestes Pursued by the Furies (1862) (

This scene, and its many renditions and reinterpretations, expose some of the stereotypes and contradictions inherent in the complex interrelationship of revenge and gender. As in the case of Orestes, revenge is frequently depicted as a mans job: women incite and men act, performing the killings that establish their masculinity and protect their honour. Yet, while conceptualised as a quintessential masculine activity, revenge simultaneously unleashes the female Furies and the violent, feminine emotions which threaten a mans reason and self-control. Hunted by the hounds of his mothers hate ( , Aesch. Cho. 1054, cf. 924), Orestes is driven to near madness by their pursuit, his manliness undone by the same act that establishes it. Women, of course, also take revenge, as when Clytemnestra kills Agamemnon to requite the sacrifice of their daughter, Iphigenia. However, scholars are divided as to whether female avengers should be interpreted as honorary men, heroes in their own right, monstrous inversions of gender norms, or conduits through which male subjectivity is formed. Implicit in these debates are also questions about how revenge plots impact on wider constructions of gender, and whether such narratives reinforce conservative gender roles, interrogate the masculine values that society prizes, or establish new ways of conceptualising women and men.

Figure I.1 William-Adolphe Bouguereaus Orestes Pursued by the Furies (1862), Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, VA, USA.

This collection takes up these questions, probing revenges gendering, its role in consolidating and contesting gender norms, and its relation to friendship, family roles and kinship structures. Spanning Western ideas of revenge in literary works from ancient Greece to early modern England, it considers how writers respond to and reimagine inherited plots and characters, exploring continuities between historical periods as well as the ways in which texts and traditions diverge.of these varied positions, arguing that while revenge functions as a repressive cultural script that reinforces conservative gender roles, it also repeatedly triggers events and actions that disturb and interrogate gender norms. Indeed, I argue here that revenges unruly energies can blur conventional male/female and animal/human binaries, challenging cultural expectations about gender and provoking wider ontological questions.

This Introduction also examines lamentation, a female-gendered activity which enables women to play an important role in revenge narratives. Particularly in earlier periods, women use lamentation to express grievances and keep the past alive, directing revenge action and, at times, influencing wider political events. However, female lamentation becomes discredited in later periods and detached from the revenge process. In early modern tragedy, female mourning no longer incites revenge. Instead, the revenger is also the mourner, whose grief inhibits the revenge process. Vengeance becomes the occasion for a confrontation with the potential purposelessness of life and the inevitability of death, opening up wider ethical and metaphysical questions and creating a new kind of tragedy which reflects on and revises earlier models. Drawing on several essays in this volume, I therefore argue that the change in lamentations status and function has wider implications for womens roles and for the gendering of the male revenger.

Next page