Contents

Page List

Guide

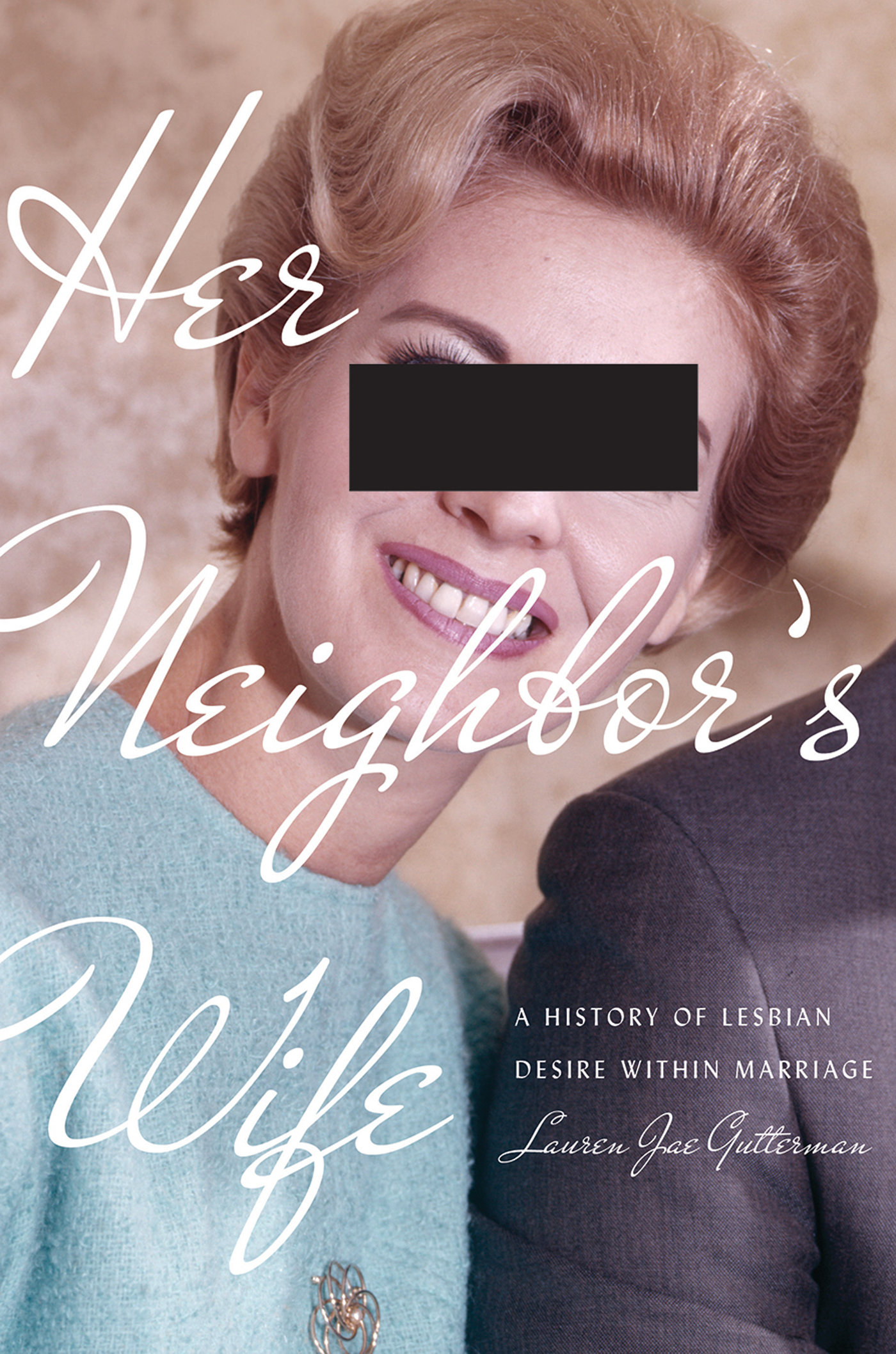

Her Neighbors Wife

POLITICS AND CULTURE IN MODERN AMERICA

Series Editors:

Margot Canaday, Glenda Gilmore, Matthew Lassiter, Stephen Pitti, Thomas J. Sugrue

Volumes in the series narrate and analyze political and social change in the broadest dimensions from 1865 to the present, including ideas about the ways people have sought and wielded power in the public sphere and the language and institutions of politics at all levelslocal, national, and transnational. The series is motivated by a desire to reverse the fragmentation of modern U.S. history and to encourage synthetic perspectives on social movements and the state, on gender, race, and labor, and on intellectual history and popular culture.

Her Neighbors Wife

A HISTORY OF LESBIAN

DESIRE WITHIN MARRIAGE

Lauren Jae Gutterman

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA PRESS

PHILADELPHIA

Copyright 2020 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A Cataloging-in-Publication record is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN 978-0-8122-5174-6

CONTENTS

Introduction

IT WAS HALLOWEEN NIGHT, 1961, in college-town Champaign, Illinois, but Mrs. Alma Routsong was not carving pumpkins. With her four daughters momentarily out of the way, likely out trick-or-treating with their father, Alma was sitting down to write at a small card table in the bedroom of her lover, Betty Deran. Alma was beginning a secret diary. An established novelist and an avid diarist, Alma wrote nearly every day in her journals, but some things were too private even to be recorded there: namely, her love affair with Betty. I switch to this book so I can say what I want to, Alma began. Betty says she will get me a lockbox to keep it in, because she too wants me to write about us, and has many times, she says, in reading an entry for some special day been disappointed by the flatness of it, the non-mention of the specialness, so we are prepared for the risks and delights of this record. By October, Almas affair with Betty was roughly four months old, and their relationship had grown more serious and more consuming than either woman could have expected. Almas secret diary provided her with a venue in which she could, like a schoolgirl, gush over Bettys intelligence, her dark hair, and her ease with people. It also allowed Alma to describe and revel in their striking physical passion.

Yet despite Almas reference to risks, and the significant measures she took to protect her diary, Almas affair with Betty was not exactly a secret. The womens lives were remarkably intertwined, and their relationship had unfolded within plain sight of their friends and family. Betty, an economist, and Almas husband, Bruce, a veterinary science professor, both worked for the University of Illinois. The women met, not at a lesbian bar in a big city, but at their local Unitarian Church. In fact, a mutual friend introduced Alma and Betty at coffee hour one Sunday in the summer of 1961. I just know you two ladies are going to love each other! she declared.

Alma initially planned to balance her marriage and her lesbian relationship until her youngest daughter reached eighteen, and if Betty had been willing to remain in Illinois that may well have happened.

This book traces the stories of women like Alma from the postWorld War II period through the 1980s. Manyif not mostwomen who experienced same-sex desires during these years were married to men at some point, yet this significant population has been neglected in histories of gay and lesbian life, as well as in histories of marriage and the family. Just as Almas relationship with Betty was not truly a secret, the history of wives who desired women has never been entirely hidden: letters, diaries, divorce records, and oral history interviews have long documented the experiences of wives who desired women. But contemporary political concerns have profoundly shaped the telling and recording of LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender) history. Historians of homosexuality have been most concerned with describing the lives of those who identified publicly as gay or lesbian, with documenting urban gay and lesbian cultures, and with tracing the roots of the modern LGBT movement. So, while many scholars have recognized the great number of women who divorced and built new lesbian lives in the 1970s, the ways in which these same women were able to act on their same-sex desires within marriage have attracted much less attention.

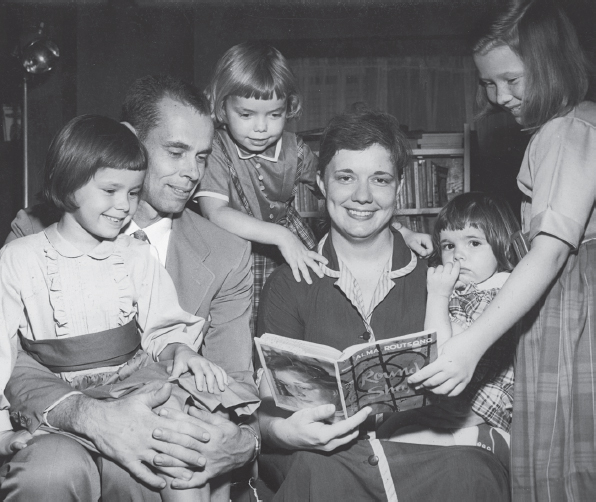

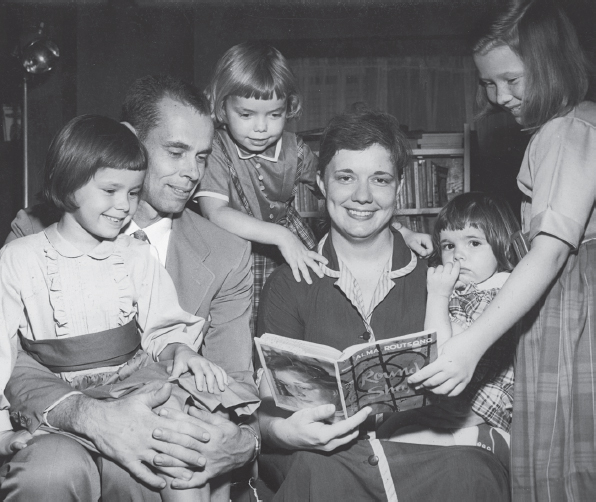

Figure 1. Alma Routsong and her family in a press photo for her novel Round Shape, 1959. Curt Beamer for the News-Gazette. From the Isabel Miller Papers, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College Libraries.

By drawing on a variety of different sources, I have gathered a group of more than three hundred wives who desired women. One-third of these womens stories come from the correspondence files of Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon, longtime lesbian activists who helped to found the Daughters of Bilitis (DOB), the nations first lesbian rights group, in San Francisco in 1955. Dating from the 1950s through the 1980s, these letters provide an uneven source base. Some married women corresponded with Martin and Lyon for years and wrote lengthy letters describing their lives in great detail. Others dashed off brief one-time notesconfirming their membership or terminating their subscription to the DOBs magazinethat convey little specific personal information, but nonetheless tell us something about how wives navigated their desires for other women. In addition to this correspondence, I use letters that married women wrote to other gay, lesbian, and bisexual groups and leaders, legal records from divorce and child custody cases, as well as the personal papers and diaries of a few established writers.

Oral history interviews complement these archival sources. Between 2010 and 2016, I conducted twenty-nine oral history interviews with once or currently married women, their children, or their lovers. In analyzing these sources, then, I try to remain attuned to the ways that hindsight and the coming out narrative affect such womens stories, shutting down other ways they might have understood their sexuality or their life choices at the time.

Although basic demographic information is not available for all the women who appear in this book, it is possible to draw a rough biographical sketch of this group. Of those women who stated or gave clues as to their age, the majority68 percentwere born between 1925 and 1946; less than a third were born between 1946 and 1964. Her Neighbors Wife is thus primarily a story about the women who created the baby boom, women who married and started families in the late 1940s, 1950s, and early 1960s. It is also, to a lesser extent, a story about their daughters, the baby boomers themselves, particularly those who were born in the first half of their generational cohort. This is a geographically diverse group: 27 percent of the wives I have identified lived in New England and the mid-Atlantic states; 26 percent lived in the West and Northwest; 25 percent lived in the Midwest; and 17 percent lived in the South and Southwest. While some of these women lived in or near major cities such as New York or San Francisco, they were more likely to be found in smaller cities, towns, suburbs, and, to a limited extent, rural areas across the nation.