Chapter 6 Preview

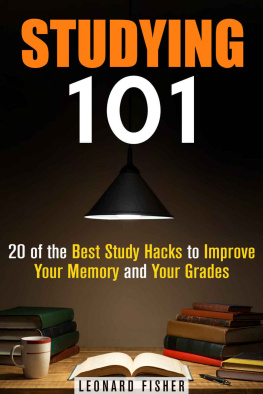

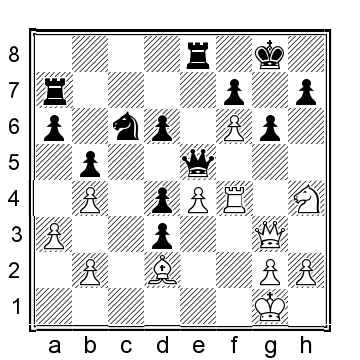

Black to move

What is the best move for Black?

(go to the ANSWER)

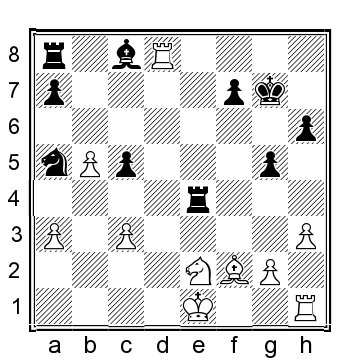

Black to move

How would you respond to Whites impending kingside attack?

(go to the ANSWER)

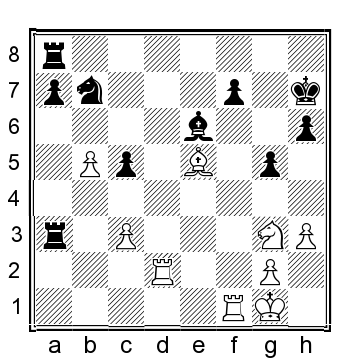

Black to move

Please suggest the best continuation for Black.

(go to the ANSWER)

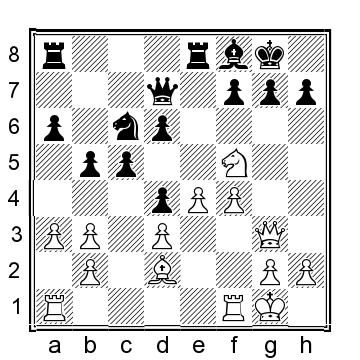

Black to move

How would you deal with Whites potential threats on the dark squares?

(go to the ANSWER)

Chapter 6

Dynamize your tactical training

In general, I think its very hard to make progress in chess without constant work on tactics, calculation, and other dynamics. They are always present even in the most subtle of games Sam Shankland.

The statement above encapsulates the role of tactics in chess study and practice. To my mind, tactics are as fundamental to chess as physical stamina is to physical sports. Imagine professional football players skipping on their sprints, gym workouts, and other types of physical conditioning. They would run out of air on the pitch after 15 minutes if they are lucky not to get injured before that. It goes the same way with tactical skill in chess. Even the most tactically gifted chess players need to practice their tactical skills and enrich their tactical intuition regularly in order to improve (remember the quote about Mikhail Tal from the first chapter).

Now, when most people think about tactical training, what do they usually do? They solve a large number of puzzles from a tactics book or online tactics trainer, hoping that the increasing amounts of such work will help them become stronger tacticians. This typical, let us call it basic, tactical training is mostly geared towards the improvement of tactical pattern recognition and calculation of forced variations. These are vital skills, because you want to be able to spot a thematic double attack combination or calculate a forced sequence when the opportunity arises. Yet, it is important to keep in mind that this is not the only way one can study tactics (more on that a bit later).

When it comes to tactical pattern recognition training, Richard Rti said, Most combinations, indeed, practically all of them, are devised by recalling known elements (...) as for the imagination it has been proved by psychologists that it cannot offer anything new, but, contending itself with combining familiar elements, can be developed by increasing knowledge of such elements. In other words, we need to perform the kind of tactics training that builds up and maintains our base of tactical elements and patterns, as it prepares us not only to spot and execute well-known tactical ideas, but also to create ever more complex and imaginative combinations in our games.

The second part of the basic tactical training is calculation training. Here is what Rti argues in the same essay: The planning of strong combinations can be learned much more easily than is generally believed. On the one hand, this ability depends upon calculation, which can naturally be developed through practice. Mark Dvoretsky fully agrees with this view on calculation, often pointing out in his works that calculation is absolutely a practical skill, it does not rely on deep ideas. To improve this skill, one should solve many exercises.

While the two types of basic tactics training, tactical pattern recognition and calculation, often go hand-in-hand, there is also a distinction to be made between them. While calculation is an integral part of tactics (you need to calculate a tactical variation), tactics are not always an integral part of calculation. We can, and often do in our games, calculate non-tactical variations, such as mutual developing sequences in the opening, piece maneuvers and plans in the middlegame, and long variations in the endgame. Thus, it is possible to practice your calculation skills with exercises from other areas of the game, as well. In addition, there are specific sub-skills of calculation that may not necessarily be related to your tactical skill, such as:

finding relevant candidate moves;

recognizing the opponents resources;

overcoming resistance in calculation;

calculation speed;

etc.

All of these aspects of calculation and more have been covered in many chess works. If you have not done such specific calculation training before, I would suggest that you start with the appropriate calculation resources recommended in Chapter 4.

Dynamics

Remember the three related tactical aspects from the start of our discussion: tactics, calculation, and other dynamics? I think that most chess players would be able to explain what exactly tactics and calculation are, but many of them might not quite put the finger on what dynamics is. The dictionary defines it as a force that stimulates change or progress within a system or process. In chess, it is one of those things that is often easier to recognize when it happens in a game than to define in words. You can definitely feel distinct dynamics in games of Judit Polgar or Veselin Topalov, for example there is always something happening in their games. However, these dynamic actions are rarely random they are usually a part of a certain tactical or strategic plot. They also typically involve a lot of interaction between the pieces and are played with the maximum economy in terms of time*, but do not necessarily lead to a forced conclusion, as in White to move and win/draw puzzles. To summarize, dynamics in chess is typically characterized by:

* Time in terms of moves or tempi.

1. initiating a purposeful change in the position;

2. time economy; and

3. a lot of piece interaction.

If we think in more practical terms, these three dynamic factors are prevalent in the following types of situations:

playing for the initiative;

playing for the attack;

sacrificing material;

double-edged positions; and

tactical complications.

Now, if you have spent many hours solving tactical puzzles and sharpening your calculation skills, but you still shy away from sacrificing a piece for uncertain compensation, avoid messy tactical positions, or get scared of the very thought of your opponent having tactical threats around your king, do you think that solving more tactical and calculation puzzles is the solution?

I hope that your answer is no. Let me suggest several more effective study methods to improve your play in dynamic positions:

analysis of double-edged positions with tactical resources for both sides;

simulations or FBM practice of games of a strong player with a dynamic playing style;

analysis of games with long-term material sacrifices in exchange for dynamic factors;

playing out tactically complicated positions in sparring games or against a computer;

solving high-traffic and tactical vision types of tactical puzzles (see the Tactics Test section at the end of the chapter);

immersing yourself in the world of endgame studies and chess problems, especially paying attention to those with prominent knight geometry and atypical tactical motives; and

attempting blindfold practices in dynamic positions whenever possible.

Next page