Hallowed Be This House

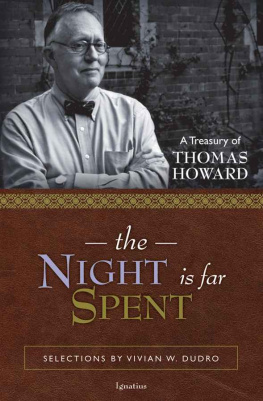

THOMAS HOWARD

Hallowed

Be This House

Finding Signs of Heaven

in Your Home

New Edition

With a Foreword by

Peter J. Kreeft

IGNATIUS PRESS SAN FRANCISCO

Cover photograph: Istockphoto

Cover design by Riz Boncan Marsella

Text 1976 and 1979 by Thomas Howard

Foreword 2012 by Ignatius Press, San Francisco

All rights reserved

ISBN 978-1-58617-712-6

Library of Congress Control Number 2012936992

Printed in the United States of America

To the memory of C. S. Lewis

Contents

Foreword

It is rare that an author and his books are equally impressive, equally convincing, equally beautiful. If the books are impressive, the author is usually a disappointment. (Rousseau is a spectacular example of this.) If the author is impressive, the books are usually a disappointment. (Why cant Mother Teresa write long, profound books that change the world as much as she did?) Thomas Howard is an exception to this rule. I have been privileged to know Tom personally, for many years (indeed, it was, I think, the Pre-Cambrian era when we first met), and I assure you that his books, his life, and his soul are the same thing : not perfect, not a canonized saint, but beautiful .

I call him Tom Chrysostom, Thomas the golden-tongued. He fondles words as a cat lover fondles kittens, juggles them as a circus performer juggles balls, plays with them as an artist plays with colors. A student once told meit is one of the most appalling sentences I have ever heardI hate words; words are my enemies. The difference between Tom and that student is almost the difference between heaven and hell; at least a good part of the difference between heaven and hell.

Toms style is one with his content. Both are paradoxical: at the same time totally simple and totally complex, like the universe; totally clear and totally mysterious, like light. The point is that the high and holy mysteries are played out in our low and ordinary lives; or, putting the exact same truth in opposite words, that our low and ordinary lives hold high and holy mysteries. It is exactly like the most primary Christian mystery of all, the Incarnation: Christ Himself, who is not really-divine-and-only-apparently-human (the old Docetist-Gnostic and new New Age Spirituality heresy), or really-human-and-only-apparently-divine (the old Arian and new Modernist heresy), or half-divine-and-half-human, like a centaur or a Greek superhero, or Mr. Spock, but divine in His humanity and human in His divinity. Thus Toms style is at the same time high and low, profound and playful, sacred and secular, heavy and light, heavenly and earthy. It is a Christlike style.

This book (and all Toms books, really, especially his other masterpiece Chance or the Dance ) have just one thing to say. But this one thing is everything, as the universe is all the things in it, or as light is all colors. (Chesterton says: One thing is needful: Everything. The rest is vanity of vanities.) The one point has many names: Holiness (or Hallowedness), Sanctifying Grace, Theosis, God-like-ness, Charity, Agape, Zoe, Joy, Exchange, Freedom, Glory, and My Life for Yours are some of its epithets. It is The Tao, The Way, The Way Things Are, the nature of all reality, because it is the nature of God.

The original title of this book was Splendor in the Ordinary . That is the burden, the gospel, the good news of the book. When we are born, we notice that even when we were in the womb we were already in this gloriously bigger and brighter world but we did not see it. When we die, if we go to heaven, we will realize that we were always in heaven even while we were on earth, but we did not see it. We were confined to this dark, narrow, little cave called the universe. But we can open our eyesthe eyes of faith, not the eyes of the fleshand see it a little through a glass, darkly, and we can call out to our fellow cave dwellers: Lift up your heads! Lift up the gates of your soul; the King of glory is constantly coming!

But this single point is mysterious as well as clear, infinitely complex as well as totally simple. In this book it is applied to a house, because a house, like the human body, is a microcosm of Everything, or at least of everything human, everything in human life. It is both one and many. The seven main rooms in a house correspond to the seven main places in life to find this thing, this point, this light of glory.

They happen to correspond also to the seven sacraments of the Church. Tom tells me he did not realize this at the time he wrote the bookindeed, he was on the road from Canterbury to Rome at that time, back in 1976and that makes it even more impressive, something natural, universal, unconscious, and inevitable. Thus the front door is like baptism, the hallway like confirmation, the dining room like the Eucharist, the kitchen like ordination to the priesthood (where the Eucharist is confected), the bathroom like confession, and the bedroom like both matrimony and extreme unction, the bed hosting both birth and death. That leaves the living room, which is for living this life, this exchange, this conversation.

This book will change your life (as Pips mysterious benefactor did for Pip in Great Expectations , or as the paupers life was changed in The Prince and the Pauper ). It will lead you out of Platos Cave. It is the glorious alternative to and refutation of The Secular City (the most depressing book I have ever read).

Open this book. Enter the glory. Discover there are more things, not less, both in heaven and on earth, than your philosophies could even allow you to dream. Read it and weep with joy.

Peter Kreeft

April 2012

The Household

The ancients used to hallow places. They set aside groves and grottoes and mountains, and built temples and shrines and enclaves. Places mattered to them. They thought that a place could be fenced off and acknowledged to be the dwelling of the god, or the spot where the god had done some memorable thing. Here was a holy well, and there was an oracle. Here was an altar, and there was a tabernacle. The landscape of antiquity is dotted with these things, and it is natural that it should be. If the gods are there, and if their influence touches our realm, then memorable things are going to happen, and we men do well to mark off the precincts. Otherwise somebody might step across a line he ought not to step across, or cut down a tree that is not available for lumber, and end up paying with his life for having missed his cues.

This is all strange to us later men, or at least quaint. We know better than to think that there are any gods about, much less gods that can be pinned down to places. If we do believe in a godor God, shall we sayhe is certainly not the sort of being who can be housed . He is everywhere. His Spirit, like the wind, blows where it will. We cannot wall him into a shrine or pen him in an oak. He fills all things, and if he dwells anywhere, it is in the hearts of people who love him.

At this point, Christians (who, unlike most twentieth-century men, share with the ancients at least the idea that we do live and walk in the presence of the unseen) are assenting. We do acknowledge and worship such a God. He has entered our history; indeed he is the Lord of our history and has acted dramatically in that history. But he has told us that his dwelling is not in temples made with hands but rather in the heaven of heavensand also with him who is of a contrite and humble spirit (Is 57:15).

Hence Christians think more about God in their hearts than God in a temple. No matter what holy places there are for Christians (and some give more weight to this than others), any Christian, when the chips are down, knows that his own body, somewhat like that of Mary, is Gods earthly sanctuary. It is to this temple that a Christian must give his most serious attention. It is more important for this to be swept and attended to than for the church building to be tidy (although there is, of course, no either / or situation: devout Christians tend to keep their churches, like themselves, clean).

Next page