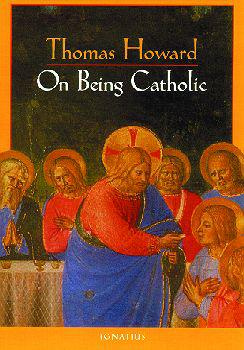

On Being Catholic

Thomas Howard

On Being Catholic

IGNATIUS PRESS SAN FRANCISCO

Cover art: Christ Giving Communion to the Apostles

(The Institution of the Eucharist), detail

Fra Angelico

From the Museo San Marco, Florence

Scala / Art Resource, N.Y.

Cover design by Roxanne Mei Lum

1997 Ignatius Press, San Francisco

All rights reserved

ISBN 978-0-89870-608-6

Library of Congress catalogue card number 96-75716

Printed in the United States of America

To my daughter, Gallaudet,

and my son, Charles,

who, with my wife, Lovelace,

are my chief joys

Contents

Foreword

In these times of crisis and discussions on religion and liturgy, often limited to secondary aspects, this book, written with the realistic intelligence of living faith by a Catholic convert, is a refreshing and renewing document. It is a beautiful book, a book of great relevance and of lasting value; it is life and contemplation put into words, based on the truth of Gods gracious gift to us in his Church.

It recalls to us the very essence of the grace of being Catholic , as the author summarizes: To be Catholic... is to live ones whole life in the gospel, to rest ones case in the pierced hands of Jesus Christ the Savior; to think of oneself as having been adopted into the whole family in heaven and earth as St. Paul teaches, to be profoundly conscious of ones place in an immensely ancient tradition... that stretches back to the beginning. It is to have been set free by Christ for the Dance called Charitywith its healing rules of renunciation, self-mastery, and virtue, and its fruits of freedom and joy, glimpsed in the Beatitudes. The image of Christ. That is a very taxing assignment, our configuration to Christ. To be Catholic is to confront all of this in the presence of the Crucifix.

The author first of all recalls the invisible depths of the divine mysteries present in the Holy Liturgy, above all in the Lords unique and everlasting Sacrifice, which unites heaven and earth in the Assembly of the Eucharist, Center of the life of the Church and of each of the faithful. To be Catholic is to live from this infinite love of the Lord Jesus Christ, inviting us to eat his Flesh and drink his Blood, and so to enter into a growing partaking of his divine life in the communion of the Most Holy Trinity, to live in this love and peace throughout all our daily life, to the glory of God and the salvation of the world (Liturgy of the Eucharist).

The reading of this precious little book, so truly Catholic, makes one rejoice greatly; ones spirit is enlightened, and ones heart is opened up in contemplating the everlasting presence to us of the overwhelming love of Jesus Christ, of the Blessed Trinity, which is the Truth and Life of the Catholic Church, and of being Catholic.

+ Christoph Schnborn

Archbishop of Vienna, Austria

The Glad Tidings

To speak of the Roman Catholic Church as glad tidings is to rouse scandal and incredulity in some quarters.

For example, some who were born into this Church will urge that their whole experience led them to conceive of the Church as of a tyrant. Whether it was a matter of having rote replies to the Baltimore Catechism drummed into their aching ten-year-old heads, or of their little knuckles being cracked with a ruler wielded by a fierce nun, or of guilt and confusion being compounded upon them in dire homilies Sunday after Sundayone way or another, they will tell us, this Church can by no stretch of fancy be thought of in connection with any very encouraging tidings. Darkness and cringing bondage would seem to them to strike the note more exactly.

Others, especially zealous non-Catholic Christian believers who have watched this Church from the outside for a lifetime, will volunteer that, far from glad tidings, what Roman Catholicism purveys by way of gospel is a travesty. Instead of the invitation to come and be set free from your bondage and sin, they will tell us, Catholicism tangles one ever more deeply in guilt and uncertainty. Instead of the bright assurance that attends the conviction that one has at last been saved, we find Catholics toiling along wondering if heaven is too much to hope for. Instead of let us therefore come boldly to the throne of grace, which we hear from St. Paul, we find peasants and Montagnards and crones in babushkas lighting candles and offering prayers at squalid shrines and grottoes in a forlorn attempt to find some modest toehold on the fringes of the Divine Mercy.

And yet others will point to history and ask what sort of gladness may be said to attach to crusades, inquisitions, revoked edicts, Borgia popes, and crafty diplomacy.

And besides all this, it is sometimes remarked, look how the simple message that brought joy to shepherds, to the poor, to the jailer in Philippi, and to the Ethiopian in his chariot, of Fear not! and Believe!look how this has been choked with penances and confessions and obligations and anathemas and Purgatory. Where are these glad tidings? Where indeed?

The effort to mount a rejoinder to such observations must allow for the earnestness of the observers. No one has cobbled up such remarks about the Catholic Church out of thin air. Something lies at the root of all these strictures. The Churchs interlocutors can point to many things that have aroused their confusion and even their wrath. Protestant witnesses, for example, have in times past cried out in agony from Catholic bonfires; and concordats have been signed between the Vatican and various states depriving powerless multitudes of their freedom to worship as non-Catholics; and too many of the Catholic faithful themselves have, no doubt, gone to Christian graves never having quite grasped the glad aspect of the tidings.

It is with these anomalies in mind that I attempt the apologia that occupies the following pages. I myself am a late comer to the ancient Roman Catholic Church. My Christian nurture occurred in a wing of Christendom that stands at a polar remove from Rome; but it is to that Protestant Fundamentalism, ironically, that I owe my having at last found my way into the Church, for it was the Fundamentalists, most notably the figures of my father and mother, who taught me the apostolic faith. They taught me that there is nothingnothing at allthat may be compared to the excellency of the knowledge of Christ Jesus the Lord. They instilled in me the immense gravity of the matter, that to obey and serve God must swallow up all other contenders for ones attention. And they taught me, I think, that the peace and order that follow upon such obedience and service, both in ones inner man and in ones household, are a treasure to be desired and sought most sedulously. Everything else is ultimately illusionary, fugitive, and perfidious.

It was from such a beginning that I set out on the itinerary that brought me eventually to the Catholic Church. I have told that particular tale elsewhere, and it is not my task to repeat it here. I would like, if I can, to put forward the senses in which it may be said of the Roman Catholic Church that, despite the most baleful charges that can be brought against her, nevertheless, to hear what she teaches is to have heard glad tidings, and to have entered truly into her life is to have found the tidings to be true. It is to have come to that fullness of the faith toward which all other renderings of the Christian gospel tend.

To assert that the Catholic Church constitutes that fullness toward which all other forms of Christian profession tend is to send us back to the question of whether man is, in his essence, religious, and if so, in what does his religiosity consist? The assertion here is that it is only in the Roman Catholic Church that mankind may discover all that is implied in his native religiosity.

Is Man Religious?

Next page