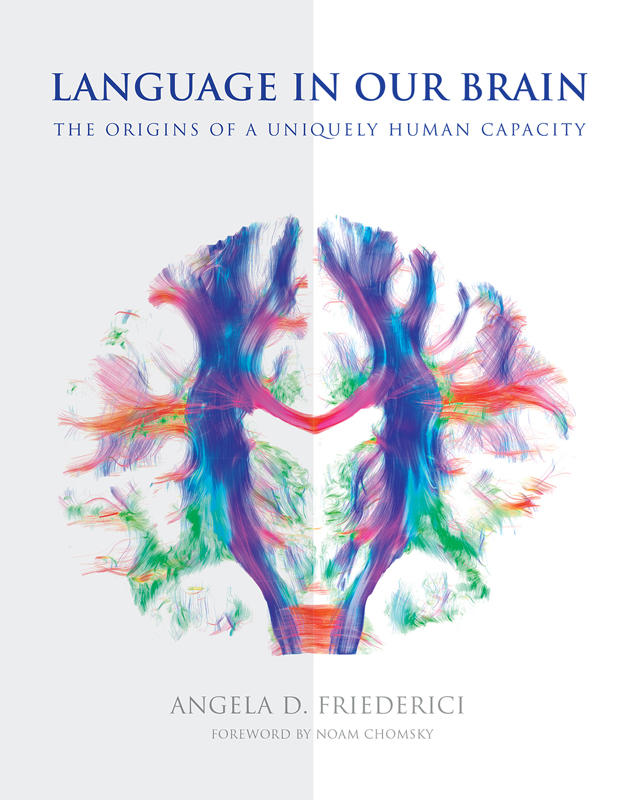

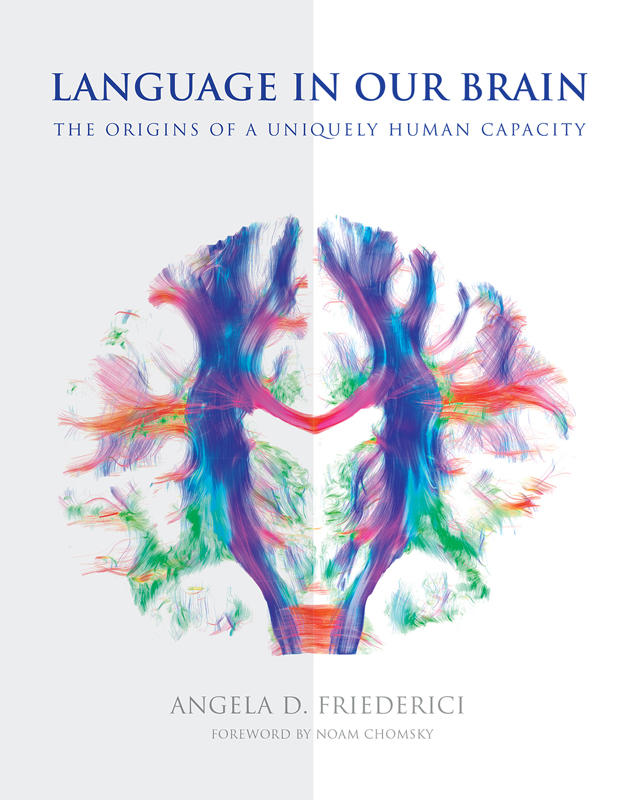

Language in Our Brain

The Origins of a Uniquely Human Capacity

Angela D. Friederici

Foreword by Noam Chomsky

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2017 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

This book was set in Syntax LT Std and Times New Roman by Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited. Printed and bound in the United States of America.

The cover displays the white matter fiber tracts of the human brain for the left and the right hemispheres provided by Alfred Anwander, Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences, Leipzig, Germany.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Friederici, Angela D., author.

Title: Language in our brain : the origins of a uniquely human capacity / Angela D. Friederici ; foreword by Noam Chomsky.

Description: Cambridge, MA : The MIT Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017014254 | ISBN 9780262036924 (hardcover : alk. paper)

eISBN 9780262342957

Subjects: LCSH: Cognitive grammar. | Cognitive learning. | Cognitive science. | Brain--Localization of functions. | Brain--Language. | Brain--Physiology. | Brain--Locations of functionality. | Psycholinguistics.

Classification: LCC P165 .F64 2017 | DDC 401/.9dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017014254

ePub Version 1.0

Es ist recht unwahrscheinlich, da die reine Psychologie zu einer wirklichen naturgemen Anschauung der Gliederung im Geistigen vordringen wird, solange sie der Anatomie des Seelenorgans grundstzlich den Rcken kehrt.

It is rather unlikely that psychology, on its own, will arrive at the real, lawful characterization of the structure of the mind, as long as it neglects the anatomy of the organ of the mind.

Paul Flechsig (1896), Leipzig

Foreword

Fifty years ago, Eric Lenneberg published his now-classic study that inaugurated the modern field of biology of languageby now a flourishing discipline, with remarkable richness of evidence and sophistication of experimentation, as revealed most impressively in Angela Friedericis careful and comprehensive review of the field, on its fiftieth anniversary.

Friedericis impressive study is indeed comprehensive, covering a rich range of experimental inquiries and theoretical analyses bearing on just about every significant aspect of the structure and use of language, while reaching as well to the ways language use is integrated with systems of belief about the world generally. Throughout, she adopts the general (and in my view highly reasonable if not unavoidable) conception that processing and perception access a common knowledge base, core internal language, a computational system that yields an unbounded array of structured expressions. Her discussion of a variety of conceptions and approaches is judicious and thoughtful, bringing out clearly the significance and weaknesses of available evidence and experimental procedures. Her own proposals, developed with careful and cautious mustering and analysis of evidence, are challenging and far-reaching in their import.

Friedericis most striking conclusions concern specific regions of Brocas area (BA 44 and BA 45) and the white matter dorsal fiber tract that connects BA 44 to the posterior temporal cortex. Friederici suggests that This fiber tract could be seen as the missing link which has to evolve in order to make the full language capacity possible. The conclusion is supported by evidence that this dorsal pathway is very weak in macaques and chimpanzees, and weak and poorly myelinated in newborns, but strong in adult humans with language mastery. Experiments reported here indicate further that the Degree of myelination predicts behavior in processing syntactically complex non-canonical sentences and that increasing strength of this pathway correlates directly with the increasing ability to process complex syntactic structures. A variety of experimental results suggest that This fiber tract may thus be one of the reasons for the difference in the language ability in human adults compared to the prelinguistic infant and the monkey. These structures, Friederici suggests, appear to have evolved to subserve the human capacity to process syntax, which is at the core of the human language faculty.

BA 44, then, is responsible for generation of hierarchical syntactic structures, and accordingly has particular characteristics at the neurophysiological level, differing from other brain regions at both functional and microstructural levels. More specifically, it is the ventral part of B44 in which basic syntactic computationsin the simplest case Mergeare localized, while adjacent areas are involved in combinatorial operations independent of syntactic structure. BA 45 is responsible for semantic processes. Within Brocas area neural networks are differentiated for language and action. These are bold proposals, with rich implications insofar as they can be sustained and developed further.

Friedericis extensive review covers a great deal of ground. To give only a sample of topics reviewed and proposed conclusions, the study deals with the dissociation of syntactic/semantic processing both structurally and developmentally. It reviews the evidence that right-hemisphere specialization for prosody may be more primitive in evolution, and that its contributions are integrated very rapidly (within a second) with core language areas for assignment and interpretation of prosodic structure of expressions. Experimentation reveals processes of production that precede externalization. The latter is typically articulatory, though since the pioneering work of Ursula Bellugi enriched by the illuminating work of Laura Ann Petitto and others, it is now known that sign is readily available for externalization and is so similar to speech in relevant dimensions that it is plausible, Friederici suggests, to conclude that there is a universal neural language system largely independent of the input modality, modulated slightly by lifelong use of sign. Brain regions are specialized for semantic-syntactic information and syntactic processing of complex non-canonical sentences. Language mastery develops in regular and systematic ways that are revealed by mutually supportive behavioral and neurological investigations, with some definite semi-critical periods of sensitivity. By ages 23, children have attained substantial syntactic knowledge though full mastery of the language continues to early adolescence, as shown by behavioral studies and observation of neural domain-specificity for syntactic structures and processes.

The result of this wide-ranging exploration is a fascinating array of insights into what has been learned in this rapidly developing field and a picture of the exciting prospects that lie ahead.

Noam Chomsky

November 2016

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Preface

Language makes us human. It is an intrinsic part of us. We learn it, we use it, and we seldom think about it. But once we start thinking about it, language seems like a sheer wonder. Language is an extremely complex entity with several subcomponents responsible for the language sound, the words meaning, and the grammatical rules governing the relation between words.

I first realized that there are indeed such subcomponents of language when I worked as a student in a clinic of language-impaired individuals. On one of my first days in the clinic I was confronted with a patient who was not able to speak in full sentences. He seemed quite intelligent, was able to communicate his needs, but did so in utterances in which basically all grammatical items were missingsimilar to a telegram. It immediately occurred to me: if grammar can fail separately after a brain injury, it must be represented separately in the brain. This was in 1973. At this time structural brain imaging such as computer tomography was only about to develop and certainly not yet available in all clinics.

Next page