For my parents, John and Sandra, with love.

CONTENTS

When Isabella Beeton first published her Book of Household Management in 1861, confectionery would have been a rare and expensive treat for all but the wealthiest members of Victorian society.

Whereas today we are used to buying sweets from almost every shop and supermarket, for the newly married Mrs Beeton, confectionery was mainly sold in high-class bakers as well as confectioners, as the two trades developed hand in hand over the centuries.

Before her marriage to Sam Beeton, Isabella certainly had shown an interest in sweet making (as well as baking), as she undertook training with the young confectioner William Barnard in the High Street at Epsom. Barnard belonged to a family of shop- and innkeepers and it is perhaps no surprise to us today that Isabellas family was suspicious of her practical interest as they wanted only the best for their eldest daughter. Isabella had developed a love of pastry making and confectionery while at finishing school in southern Germany, and so her parents indulged the young Isabella in her very modern interest as this was the only sort of culinary training that was thought suitable for young women to undertake.

For the general population, sweets were a treat to look forward to at festive gatherings such as Christmas or Easter. Throughout the country, annual agricultural fairs were made more special by the presence of journeyman sweet makers who travelled from county to county, selling their delights. Candy canes, barley sugar, perhaps even a block of the newly developed Frys chocolate would have vied with the best luxuries money could buy. As Isabella grew up, it is very possible that she would have marvelled at sweets on sale at her fathers Epsom racecourse grandstand as the crowds enjoyed their day at the races.

Virtually all sweets are based on sugar, which was historically prized, partly because of its rarity and therefore its expense. Since the earliest 14th and 15th-century written recipes, honey had been used to sweeten fruit, bread and nut pastes to create some of the earliest British confections. Sugar was reserved for creating magical sculptures and for crystallising fruits and flowers, something that Elizabeth 1 was particularly fond of.

Medieval confectioners and medics considered sugar to be the most perfectly balanced food, and as such afforded it medicinal qualities as it was thought to be able to bring the body back to perfect health. Boiled sugar sweets, strongly flavoured with menthol, aniseed or liquorice (which we still enjoy today) give a hint that sugar has for centuries been considered beneficial to health.

As the worldwide production of sugar grew in the 16th and 17th centuries its use percolated down from the royal court to be used much more widely in baking and confectionery, so that when Isabella was writing her book, it was more affordable and relatively widely available to the home cook.

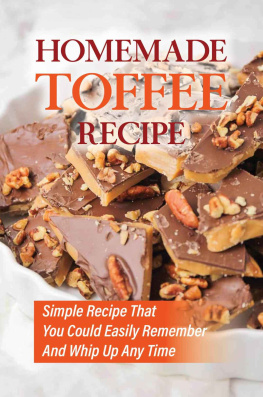

Making sweets in Isabellas day, however, was intensive labour, often requiring great patience and dedication. White sugar came in the form of huge cones, or loaves, of hard crystalline sugar that had to be crushed and powdered to use in preserves or to candy fruit. To make even the simplest barley sugar twist, hardworking housewives had to remove the impurities in the sugar with egg whites.

Around the time that Isabella was writing her Book of Household Management, pioneering chocolatiers like Francis Fry were developing the very first chocolate bars, which Isabella considered special enough to be presented with a range of fruits and nuts at the end of a dinner. Meanwhile, in Switzerland, Rudolphe Lindt and Daniel Peter were taking advantage of Nestls powdered milk to add creaminess to the very first milk chocolate.

The Victorian sweetshop would have contained many of the sweets we still eat today barley sugars, nougat and chocolate bars to name a few. Walk into an old-fashioned sweetshop today and you will almost without doubt be transported back to your childhood. Jars of Everton toffee, sherbet fountains, fruit jellies and mint fondants abound and so many of them are derived from historic recipes. Since Isabella wrote her book, technology has allowed confectioners to appeal to our love of sugar in ever more imaginative ways but we never forget that simple hit that our first taste of confectionery gave us.

THE RECIPES

Isabella Beeton published many recipes for traditional confections, notably fruit pastes and jellies, which in Victorian England were a means of preserving fruits and nuts with sugar in order to prolong their shelf life in the kitchen. Isabellas recipes escort the reader through the seasons from making candied orange slices in the winter, through to summer preserves of raspberry and strawberry, and finally autumnal apple pastes, similar to the Spiced Apple and Cinnamon Pastilles recipes in this book.

Since Isabellas time of writing, much has changed in the sweetshop the development of fudge, soft caramels, and the ever expanding range of chocolate available for the home cook to use. This book reflects the evolution of our traditional sweetshop and is packed full of new recipes for you to try at home.

If you have never made sweets before, there are so many simple recipes here that are achievable for the novice cook. Fruit pastes and fresh fruit jellies are delicious and a great place to begin as they require only basic techniques. For the more adventurous, there are tempting recipes for moulded chocolates, nougats and fudges. All the recipes have been devised to work in a simple modern kitchen with little special equipment so go ahead and experiment. You can be sure that whatever the end result looks like, your friends and family will be glad to help you sample them.

Sweets, in all their variety, have an enduring appeal to young and old alike and what nicer gift to give than a pretty box of homemade caramels or fudge? Why not enter Mrs Beetons sweetshop and see what you can create?

Granulated white sugar is derived from two main sources: sugar cane and sugar beet. Until the mid-18th century, sugar cane was the only known source of what we know as sugar, be it brown or white. Other natural sweeteners existed of course, but these honey, and tree syrups such as maple and birch are less suitable for sugar work. Only pure sugar, consisting of sucrose crystals, was capable of being melted and then worked into magical clear sheets, moulded into fantastical shapes and spun into webs.

Next page