CONTENTS

HOW TO USE THIS EBOOK

Select one of the chapters from the and you will be taken straight to that chapter.

Look out for linked text (which is in blue) throughout the ebook that you can select to help you navigate between related sections.

You can double tap images and tables to increase their size. To return to the original view, just tap the cross in the top left-hand corner of the screen.

INTRODUCTION

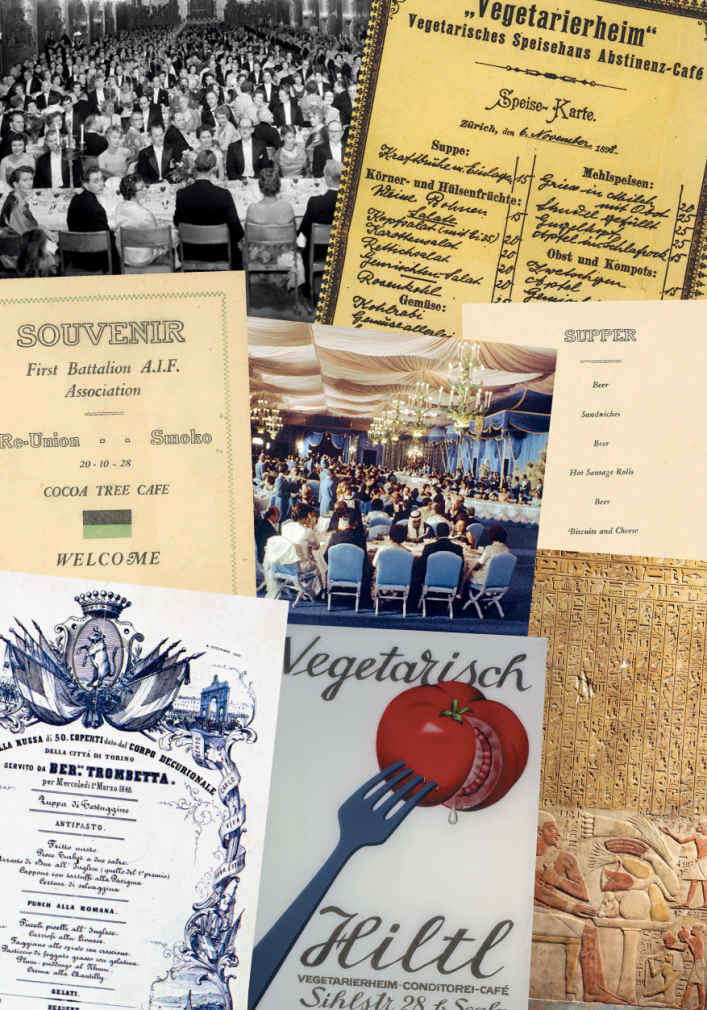

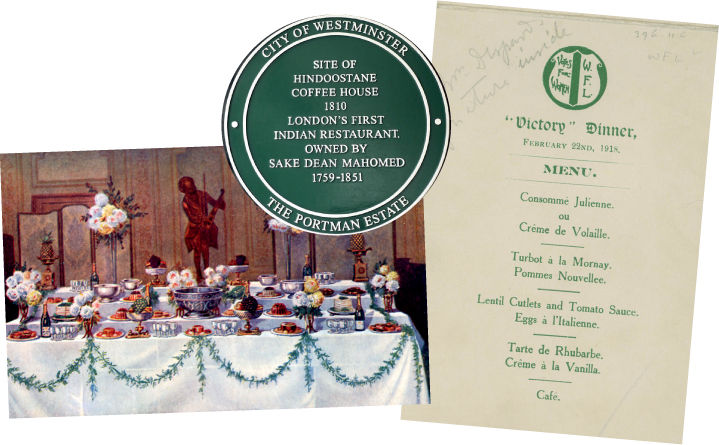

MENUS ARE MUCH MORE THAN MERE LISTS OF DISHES. FROM THE DAWN OF MANKIND TO THE PRESENT DAY, THESE EVERYDAY AND OFTEN OVERLOOKED ITEMS HAVE EXTRAORDINARY STORIES TO TELL. THEY OPEN DOORS TO SCENES OF EXTRAVAGANCE AND AUSTERITY, MIGRATION AND ASSIMILATION, WAR AND CONQUEST.

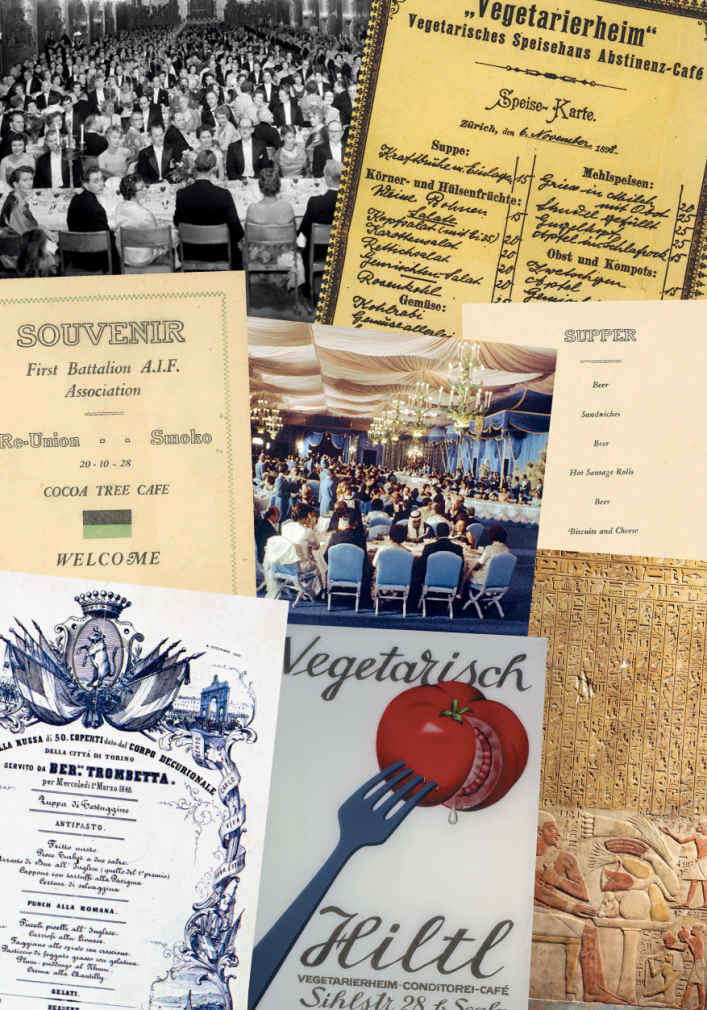

The word menu itself comes from a French term indicating something small or detailed, and further back from the Latin minutus, used to describe an item that has been reduced in size. Four thousand years ago, in ancient Mesopotamia, people were putting together divine menus on clay tablets for their gods (who apparently enjoyed roast goat, cakes and plenty of salt, washed down with substantial amounts of alcohol). In China, menus for high days and holidays are found during the Song Dynasty (9601279), including various impressive selections in one semi-anonymous civil servants twelfth-century memoir, Dreams of Splendour of the Eastern Capital. The earliest European menus appeared in France in the eighteenth century: huge broadsheet-sized pieces of paper, crammed with hundreds of dishes in tiny print that made them look like a prototype classified ads section.

Since then, we have seen the arrival of highly decorated menu cards, menus that come in their own leather binding with tassels, handwritten menus, childrens menus, even edible menus. And as with other ephemera such as football cards, postcards or film posters, people are starting to realise that menus offer us the chance to understand the past in ways weve never previously considered.

We eat to survive and we eat to celebrate. But this is not really a book about food its about understanding what these culinary snapshots can tell us about certain times and places in our global history.

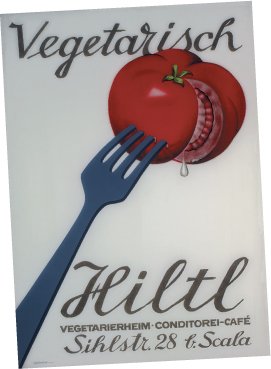

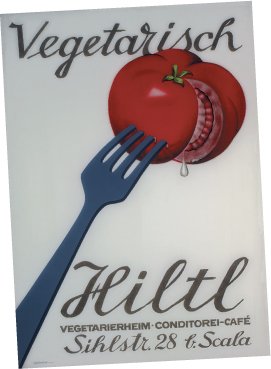

With over 40,000 years to pick from, its been tricky weighing up which selections to serve and which to send back, whittling it down to the most fascinating. Yes, there has to be a place for ridiculously over-the-top royal banquets. But weve spread the net far wider than that. From Aztec cannibals to Swiss vegetarians, and from the first meal in space to the last one on the Titanic, the following pages even feature menus that were never actually cooked and served the Cratchits of Dickens A Christmas Carol only ever celebrated 25 December on the page.

Before the middle of the nineteenth century, very few of these menus were written down. So while the more modern ones may have been propped up against the salt and pepper pots, others have been pieced together from instructions to kitchens, accounts in diaries and even scientific research into the dental plaque of ancient corpses.

Together, they form an la carte selection that reveals something unexpected, curious or just plain shocking about the people who prepared them, the people who ate them and the worlds they lived in. After youve read this book, youll never look at a pineapple in the same way again.

CHAPTER ONE

TRAVEL AND ADVENTURE

FROM RECORD-BREAKING CANAPS IN THE AIR TO AN IRONIC ICE TWIST ABOARD THE TITANIC, THIS CHAPTER ALSO SHOWS YOU HOW TO COOK A WALRUS, REVEALS THE FATAL RESULTS OF GETTING A MENU VERY WRONG INDEED, AND EXPLAINS WHY CHILLI SAUCE IS SO POPULAR IN SPACE.

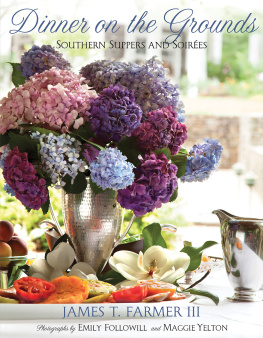

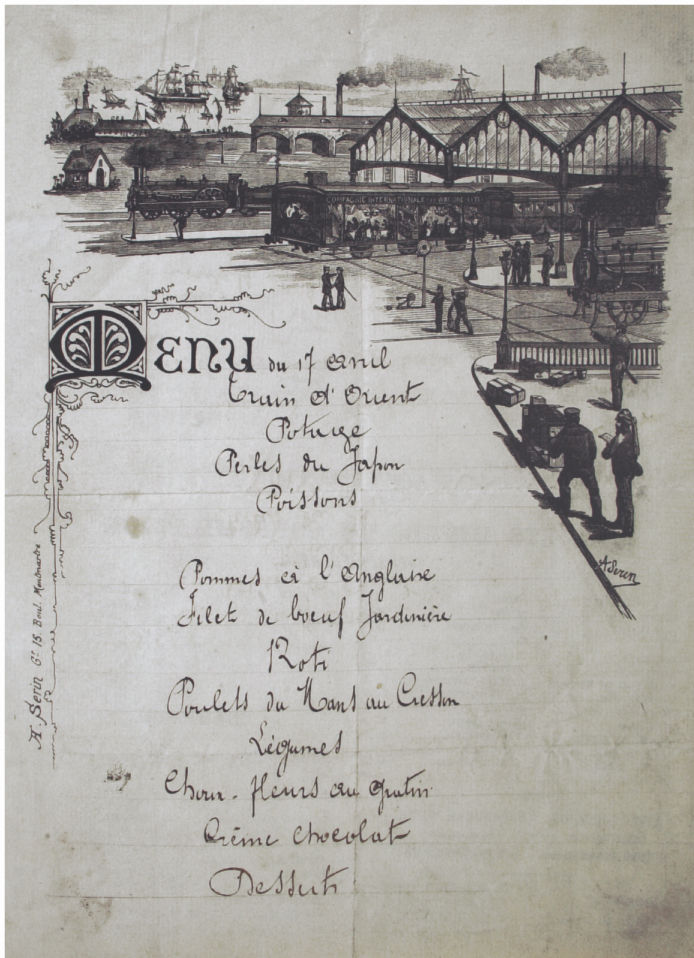

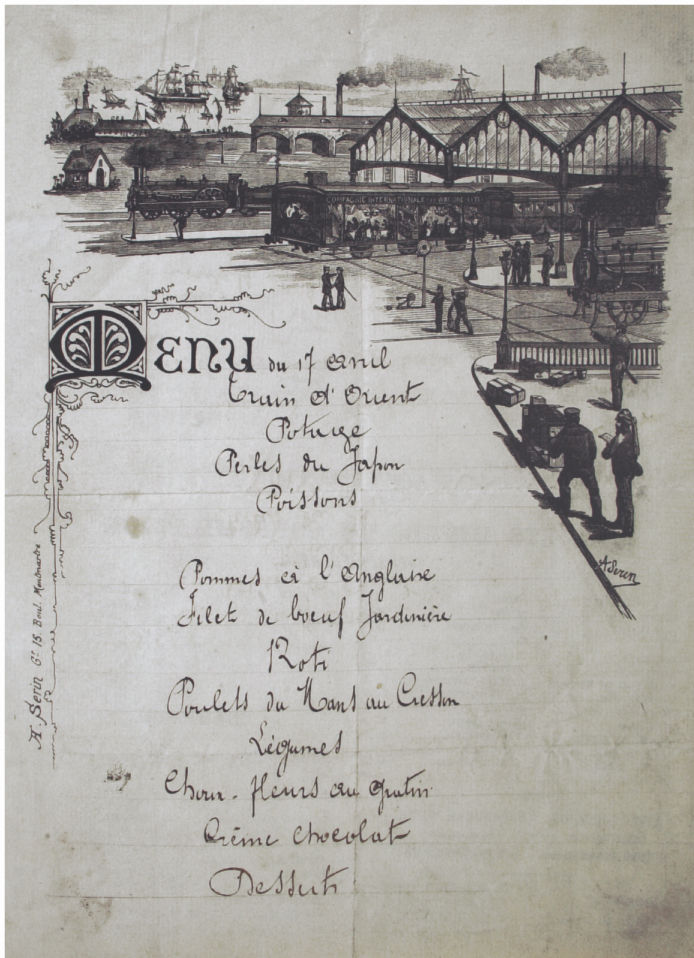

DINNER ON THE ORIENT EXPRESS

Paris to Constantinople, 17 April, 1884

I N 1883, ENGINEER AND ENTREPRENEUR GEORGES NAGELMACKERS STARTED running a luxury train service aimed at wealthy travellers looking for considerable comfort as they made their way across Europe. The Orient Express quickly became a byword for lavishness, using the white heat of late nineteenth-century technology to provide passengers with central heating, gas lighting and hot water on board. Essentially, it was a five-star hotel on wheels.

The opulence stretched to the restaurant car, where renowned French glass designer Ren Lalique was brought in to decorate the walls with glass panels inlaid in Cuban mahogany. The ceiling was covered with embossed leather from Cordoba, the walls with tapestries, and the tables in white damask with intricately folded napkins, crystal goblets and silver cutlery. In a series of first-hand reports from the inaugural journey, the Paris correspondent of The Times, journalist Henri Opper de Blowitz who compared it to a banqueting hall noted that the curtains of the restaurant car were deliberately raised before the trains departure so that onlookers could see what they were missing out on.

Potage

Perles du Japon

Poissons

Pommes langlaise

Filet de boeuf Jardinire

Roti

Poulet du Mans au cresson

Legumes

Chou-fleur au gratin

Crme chocolat

Blowitz was also impressed with the menus, prepared en route in the tiny kitchen at the end of the dining car, which he said vie with each other in variety and sophistication. However, the impressive-sounding French terminology masks what to 21st-century ears sounds a little on the nursery food side perles du Japon is tapioca, pommes langlais are boiled potatoes and chou-fleur au gratin is cauliflower cheese.

But the menu also featured one of the most popular dinner centrepieces of the age, filet de boeuf jardinire. It was a classic of French haute cuisine and made it onto the menu of the extravagant Bradley-Martin Ball at the Waldorf in New York in 1897. The larded, roasted and glazed filet was presented on a long dish, often raised on a special pastry frame or a bed of rice for added grandeur, then surrounded with vegetables (the jardinire element including cauliflower, carrots, and beans) arranged in alternating colours. The whole thing was held together with special hatelet or attelet skewers which had highly decorative tops. It was served with a barnaise sauce.

Menus in the 20th century continued to impress. In 1907, passengers would start their meal with scrambled eggs with truffles, moving on to foie gras aspic, and roasted Styrian goose. By 1925, they could also enjoy a classic French dish, glace plombires