Contents

How to Use This Ebook

Select one of the chapters from the and you will be taken straight to that chapter.

Alternatively, jump to the to browse recipes by ingredient.

Look out for linked text (which is blue) throughout the ebook that you can select to help you navigate between related sections.

You can double tap images to increase their size. To return to the original view, just tap the cross in the top left-hand corner of the screen.

Foreword by Alice Waters

Darina invited me for my first visit to Ballymaloe in her characteristic expansive fashion: Come any time! she told me. Celebrate your birthday here! I had, of course, heard of the Cookery School and knew about the groundbreaking work that Darina was doing with Irish food but even so, I was not prepared for the full attraction of the place. The first time I came, I stayed in the hotel that Myrtle Allen, Darinas mother-in-law, had created, and it was magical: windows that opened right onto the garden, freshly picked flowers brought into your room every day. They always had a big buffet on Sundays and invited all their family and friends, with Myrtle and her husband Ivan there at the end of the table. I was so touched by those dinners, and the fact that I was so effortlessly included in them. The message was always come as you are, bring your friends, and join us on Sunday night. It was such a loving, lively scene every Sunday: the kids in the family would come in still dripping from the sea and have this beautiful meal around the table with their parents, aunts and uncles, cousins and grandparents. Sometimes one daughter would sing, or another would play music for the hotel guests. This is how Ballymaloe is: you are instantly made to feel completely at home you are included, no matter what.

Darina took me out to see the Cookery School, and we did everything: we went out to the lobster boats in Ballycotton and saw the daily catch, visited the fat, happy pigs that rooted through the fields, gathered herbs from the garden and eggs from the henhouse. The School at that time was already a bustling, well-established institution, but was ever-evolving: they were developing their greenhouse, making cheese from the milk of their Jersey cows, inviting renowned chefs from all over the world to teach classes, and, of course, teaching all the fine forgotten traditions of Irish cooking. I remember Darinas brother Rory, a chef and teacher himself, cooked up a soup for me with wild garlic, which remains one of the best things Ive ever had. I learned about the sweet, milky pudding they make thats so delicious, thickened with foraged carrageen moss, that my daughter Fanny now loves; and Darinas husband Tim taught me to make the Irish soda bread I now make every Christmas. Almost every year since that first visit I have found myself back there, celebrating my birthday with friends it seems I have known forever.

As I have returned over the years, I have watched the School change and grow as Darina has become one of the most prominent voices in Irish food politics, and a vital leader in the Slow Food movement. Last year, at Ballymaloes first ever Literary Festival of Food and Wine, she invited the greatest chefs, authors, and voices in food to gather and exchange ideas, from Stephanie Alexander to Madhur Jaffrey, Claudia Roden, David Thompson, David Tanis and so many more. Darina is interested in the big picture of culture, forever challenging herself and others to expand the conversation about food into something deeper and more meaningful.

I think of Ballymaloe Cookery School as the very best sort of cooking school, and I send as many people to it as I possibly can. It is so exquisitely beautiful you are always close to nature, digging your hands into the dirt, smelling the salt air. This is the sort of hands-on, immersive experience of cooking that is so important to impress upon people right now in order for them to understand the broader context of sustainability. I love how Darina takes her family and friends to have breakfast on the rocks down by the sea bringing rashers of bacon, eggs, jam and marmalade shes made and freshly baked bread and everyone sits down on the big, soft grass by the side of the ocean and eats together. How can a young person or an older one, for that matter! not be seduced by that vision? I believe almost everyone who visits Ballymaloe Cookery School comes to think of it as a home away from home, much as I have it is impossible not to fall in love with the way of life there. Ballymaloes great and powerful message is not just about bringing back an appreciation of food and taste, but an understanding of the culture of food, and of Ireland: a culture of stewardship of the land, tradition, hospitality, and, above all, beauty.

Introduction

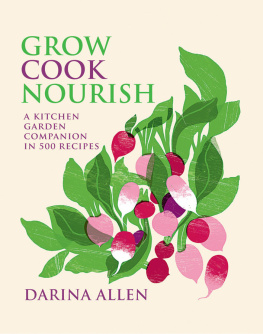

The Ballymaloe Cookery School opened on 5 September 1983 in converted farm buildings in the courtyard behind our house on the farm in Kinoith. I co-founded the School with my brother Rory OConnell and it was the culmination of several years of planning and soul-searching.

I first came to work in the kitchens at Ballymaloe House fresh from the School of Hospitality Management and Tourism on Cathal Brugha Street, Dublin, on 16 June 1968. I had heard about Myrtle Allen, a farmers wife down in East Cork, who had opened a restaurant in her rambling old country house in the midst of a farm in Shanagarry, close to the little fishing village of Ballycotton. The menu was written every day depending on what was in season and available on the farm and in the gardens. Fish and shellfish came from Ballycotton and were added to the menu when the fresh catch was landed in the late afternoon. This was extraordinary at a time when most restaurants wrote their menu when they opened and it remained the same ten years later.

The food at Ballymaloe House was made from scratch every day. We shelled broad beans and peas and made ice cream from the fresh Jersey milk and cream. Veal, or rather baby beef, came from the male calves, fresh pork from the pigs in the farmyard, freshly laid eggs from the hens who fed on the food scraps from the restaurant, watercress from local streams. Local children foraged for blackberries, damsons, sloes and wild mushrooms and brought them to the kitchen door; Myrtle paid them generously and incorporated the fruits of their efforts into the menu. An older generation brought wild bilberries from the Knockmealdown Mountains and harvested carrageen moss from the little rocks in Ballyandreen after the spring tides. Berries and fruit came from the walled garden; tomatoes, cucumbers and lettuce came from the greenhouses in Shanagarry. In autumn over 15 varieties of apple came from the orchards around Kinoith and in May baskets full of asparagus came from the sandy field near the beach in Ballynamona.

I worked side by side with Myrtle and soaked up everything she said like a sponge; she was a gentle and patient teacher with an unerring belief in the importance of good raw materials. I soon realised that if you start off with fresh, naturally produced local food in season, then it is easy to create something utterly delicious, whereas mass-produced, denatured ingredients require a magician to make them taste good thats where those fancy sauces and twiddles on top are needed to compensate for the flavour that is not there originally.

Next page