Copyright 2022 by Dorothy Roberts

Cover design by Ann Kirchner

Cover images copyright Gabriel (Gabi) Bucataru/Stocksy.com; Elnur/Shutterstock.com

Cover copyright 2022 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Basic Books

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.basicbooks.com

First Edition: April 2022

Published by Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Basic Books name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Roberts, Dorothy E., 1956 author.

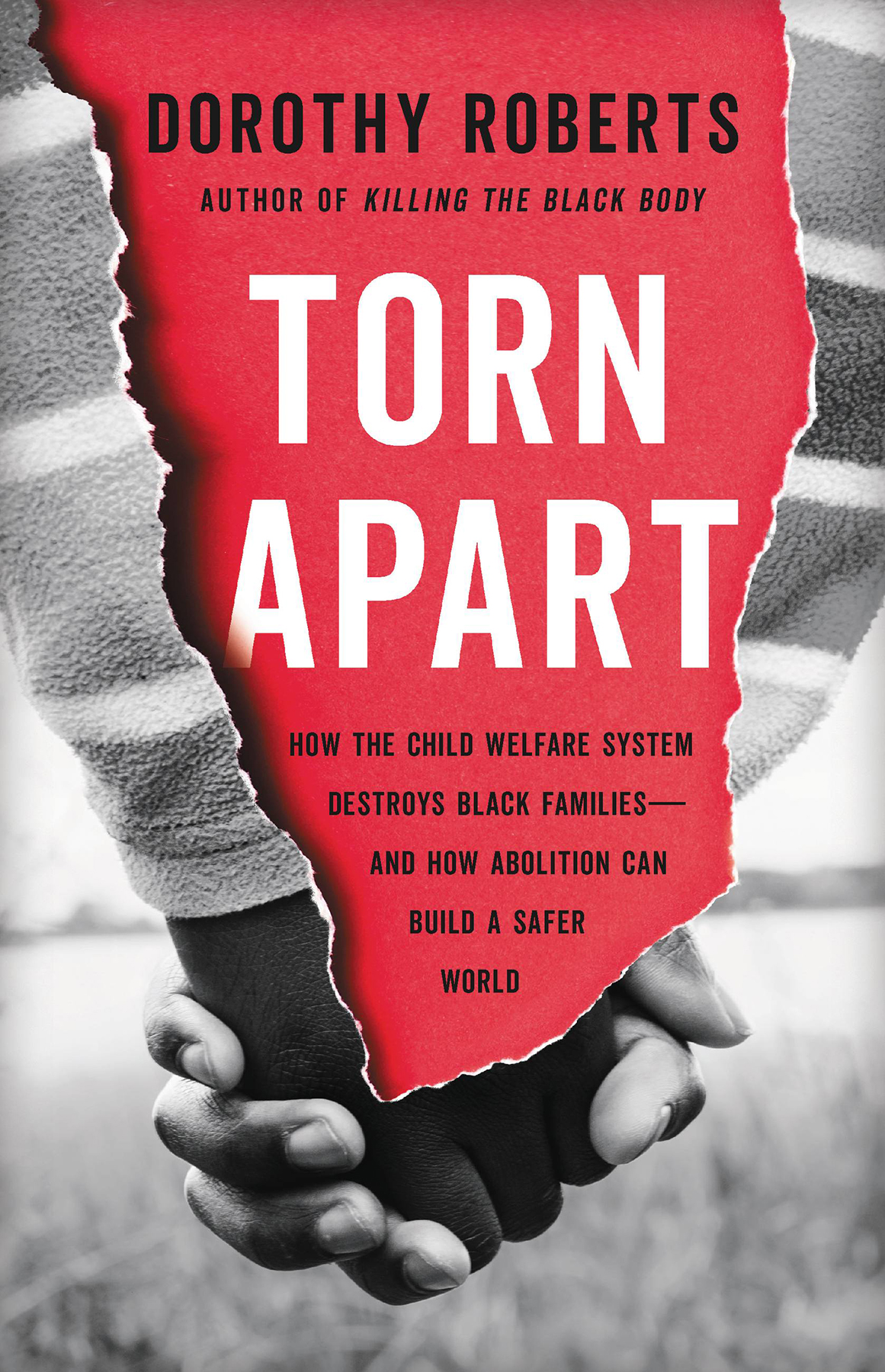

Title: Torn apart : how the child welfare system destroys black familiesand how abolition can build a safer world / Dorothy Roberts.

Description: First edition. | New York : Basic Books, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021036512 | ISBN 9781541675445 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781541675452 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Child welfareGovernment policyUnited States. | African American familiesGovernment policy. | African American familiesSocial conditions. | Racism in social servicesUnited States. | Social work with African American children.

Classification: LCC HV741 .R6225 2022 | DDC 362.70973dc23/eng/20211202

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021036512

ISBNs: 9781541675445 (hardcover), 9781541675452 (ebook)

E3-20220202-JV-NF-ORI

For my granddaughters, Akari and Josephine

SHATTERED BONDS

My book Shattered Bonds: The Color of Child Welfare , published in 2001, documented the racial realities of the child welfare system in America. At the time, more than a half million children had been taken from their parents and were in foster care. Black families were the most likely of any group to be torn apart. Black children made up nearly half of the US foster care population, although they constituted less than one-fifth of the nations children. That made them four times as likely to be in foster care as white children. Nearly all the children in Chicagos foster care system were Black. The racial imbalance in New York Citys foster care population was also mind-boggling: out of forty-two thousand children in the system at the end of 1997, only thirteen hundred were white, though a majority of the citys children were white. That year, one out of ten children in central Harlem had been placed in foster care. Today, stark racial disparities continue to mark foster care in Chicago, New York, and other cities.

I was floored by these astonishing statistics when I first encountered them in the 1990s while working on my first book, Killing the Black Body . I had been researching the arrests of numerous Black mothers across the country for being pregnant and using crack cocaine. Racist myths about them giving birth to so-called crack babies, described as irreparably damaged, bereft of social consciousness, and destined to delinquency, had turned a public health issue into a crime. I saw the prosecutions as part of a long legacy of oppressive policies, originating in slavery, that devalued Black women and denied their reproductive freedom. As I focused on the criminal punishment of Black womens childbearing, I discovered a far more widespread repression of Black mothers for prenatal drug use: the forcible removal of their newborns from their custody.

The war on crack cocaine in Black communities in the 1980s and 1990s included testing Black pregnant women and their babies for drugs and reporting them to child welfare authorities at high rates. The governments main source of information about prenatal drug use was hospitals reporting of positive toxicologies to law enforcement or child welfare agencies. This testing was performed almost exclusively by public hospitals that served poor communities of color. One study published in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine in 1990 examined the results of toxicological tests on pregnant women who received prenatal care in public health clinics and in private obstetrical offices in Pinellas County, Florida. The researchers found that, despite similar rates of positive test results, Black women were almost ten times more likely than white women to be reported to government agencies. Neonatal wards in urban hospitals were filling with Black babies who couldnt go home, labeled by the press as boarder babiestaking up space that could be used for treating sick children, the Los Angeles Times reported in July 1989. News stories typically blamed their crack-addicted mothers for abandoning them, failing to mention that most of the babies languishing in hospitals had been taken from their mothers at birth.

Investigating the racial disparities in reporting newborns for drug exposure and separating them from their mothers led me to the broader child welfare system, which I argue in this book is more accurately described as the family-policing system. Its racial makeup immediately aroused my suspicion. If this system were truly devoted to protecting children and promoting their welfare, why werent the vast majority of its clients white? The United States has consistently reserved its best resources for white people; Black people have had to fight tooth and nail to gain access to services meant for whites only. Conversely, the institutions where government has confined Black people, like segregated schools, housing, and prisons, have been substandard. Why would this state system that takes children from their parents be any different?

Whats more, America has never viewed Black children as innocent victims in need of protection. White Americans literally see Black children as older than they are. In the criminal punishment system, Black children are far more likely than white children to be charged as adults, caged in adult prisons, and held in solitary confinement. Black girls and boys are even kicked out of preschool at higher rates. The police shooting of twelve-year-old Tamir Rice while he played in a park, the confinement of six-year-old Nadia King in a mental health facility for throwing a tantrum in kindergarten, and the suicide of Kalief Browder after he spent years in solitary confinement on Rikers Island for allegedly snatching a backpack exemplify the violence the US state inflicts on Black children. Kids were being sent away simply for being alive in a place where war had been declared against us, writes Black Lives Matter cofounder Patrisse Cullors. The claim that the United States runs a system for Black families that is immune from this vicious posture against Black children and operates instead out of concern for them seemed patently absurd. The fact that the family-policing system so disproportionately enmeshes Black families was the biggest clue that its aim wasnt child welfare.