2019 Deutsches Kulturforum stliches Europa

Verlag und Druck: tredition GmbH, Halenreie 40-44, 22359 Hamburg

ISBN |

e-Book: | 978-3-7497-9851-3 |

Das Werk, einschlielich seiner Teile, ist urheberrechtlich geschtzt. Jede Verwertung ist ohne Zustimmung des Verlages und des Autors unzulssig. Dies gilt insbesondere fr die elektronische oder sonstige Vervielfltigung, bersetzung, Verbreitung und ffentliche Zugnglichmachung.

Off to Sea!

German-speaking Emigration from Eastern Europe around 1900

Issued by the German Cultural Forum for Central and Eastern Europe

Translated from the German by Sheila Brain

Cover-illustration: The Snow Township Baseball Team, McLean County, North Dacota

We acknowledge our thanks to all the archive-holders, institutions, private persons who have made material available for our use. Persons or institutions that claim rights on illustrations are requested to contact the German Cultural Forum for Central and Eastern Europe.

2015 by Deutsches Kulturforum stliches Europa for the German book edition Nach bersee.

Deutschsprachige Auswanderer aus dem stlichen Europa um 1900

2019 for the English E-Book

Deutsches Kulturforum stliches Europa

Berliner Str. 135

D14467 Potsdam

www.kulturforum.info

The German Cultural Forum for Central and Eastern Europe is committed to a sophisticated and forward-looking debate on the history of those areas of Eastern Europe where Germans used to, or still live. The Forum organizes discussions, readings, exhibitions, concerts, prize-givings and conferences. It publishes non-fiction, cultural travel guides, readers and coffee-table books in The Potsdam Eastern Europe Series.

All rights reserved.

Editor: Ariane Afsari

English translation by: Sheila Brain

Reader of the English translation: Jennifer St. Thomas, Ariane

Afsari, all authors

Design: Hana Kathrin Stockhausen

Layout, e-book-production: Sabine Abels, Hamburg, www.ebook-erstellung.de

Made in Germany.

ISBN 978-3-936168-80-8

Contents

Introduction: Europe as a continent of migration

Jochen Oltmer

From Klemzig to Klemzig: The first Prussian settlers in South Australia

Anitta Maksymowicz

19th Century migrants to New Zealand from Bohemia, and their descendants

Wilfried Heller

Overseas emigration from Bukovina

Halrun Reinholz

Galician Jews on the journey to New York

Klaus Hdl

From neighborly support to the insurance business: Transylvanian Saxons in the USA

Harald Roth

The Germans from Russia in the Americas: A Story of Retention and Transformation

Eric J. Schmaltz

Plautdietsch speaking Mennonites

Gz Kaufmann

Russian-German Songs of Emigration: From Record of History to Cultural Memory

Ingrid Bertleff

Those who have abandoned their homeland Places where emigration history can be experienced.

Wolfgang Grams

Ellis Island Migration to a Museum

Tobias Weger

Index of References

Index of Names

Index of Places

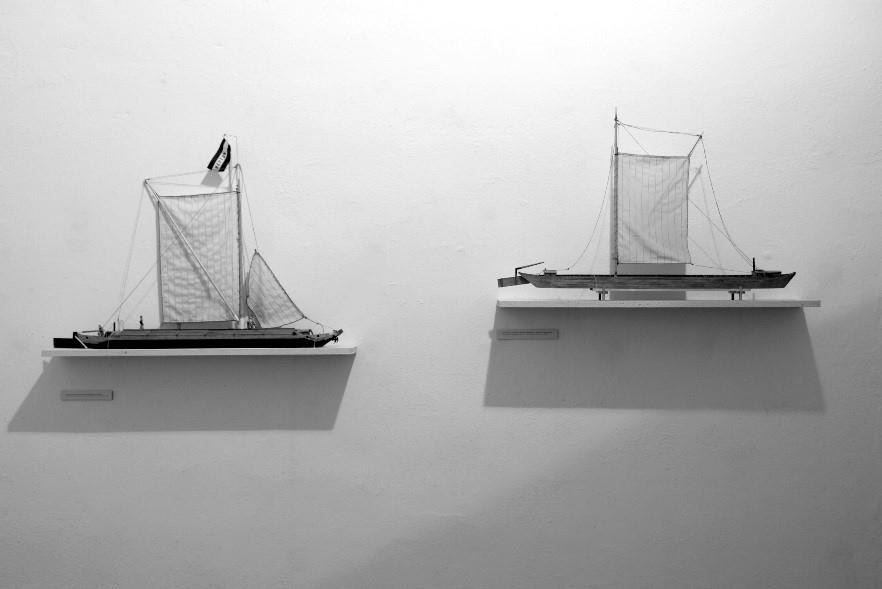

Models of small boats used on the river Oder, loan of the city museum of Neusalz/Nowa Sl

Introduction: Europe as a continent of migration

Jochen Oltmer

Human history is a history of migration. Since pre-historic ages, migrant flows of population across territories have been a central element of adapting to environmental circumstances as well as to social, economic, and political challenges. In recent centuries migration has changed the world: there are countless examples of the extent to which the composition of local populations, the development of employment markets and of cultural and religious orientations have been influenced by migrations related to employment, living conditions, flight, expulsion, or deportation. Migration is likely to remain a global topic for the future. This is made clear for example by current debates about the consequences of further growth in the world population, the ageing of societies in the rich Global North, climate change, or the shortage of skilled specialist workers for increasingly complex and tightly interconnected international knowledge-based corporations.

Migration can be understood as a long-term geographical relocation of the focal point of life for individuals, families, groups, or indeed for a whole population. Distinctions can be made between different manifestations of geographical population movements. This particularly relates to migrations for the purpose of work or resettlement, nomadic movement, migration for education, training, and cultural reasons, for marriage, for economic improvement, as well as forced migration. Disregarding forced migration for the moment (mainly flight, expulsion, and deportation), then people on the move between geographical and social locations, whether individuals, families, or groups, are mostly seeking to improve their opportunities for employment, places to settle, job markets, education, training, or marriage, or just to get a new chance in life. The decision to migrate is a result of personal choices or new arrangements in family economic situations. There may indeed be no alternative actions for individuals and families to take, especially not when there is a real threat of existential need because of economic, social, or environmental crises.

In that context belong the intercontinental migrations of the 19th and early 20th centuries, which led some 55 to 60 million Europeans to other parts of the world. The migration overseas of German-speaking settlers from eastern parts of Europe in the 19th and early 20th centuries makes up one element of this extensive, continent-wide, and geographical movement of population. For these migrations, which were directed towards the transformation of economic and social opportunities, there was primarily an economic gap between the region of origin and the target region. This should however in no way be understood as referring to marked differences in economic development between two global or continental macro-areas, but rather more as being restricted to individual small-scale market sectors. Access to markets was driven by the specific social characteristics of individuals or members of families or groups, especially sex, age, and position in the family cycle, occupation and qualifications, along with personal attributes (especially with regard to ethnicity or nationality), all of which were often bound up with privileges and birth rights, and affected their perception of the opportunities offered by migration.

Systems of communication also motivated and gave structure to geographical movements of population, and the extent to which migration was understood as an economic alternative for individuals or families depended decisively on a knowledge of the target location, along with the route to get there and the opportunities available. In order for migrations for the purpose of work, education and colonization to reach a certain scale and a specific duration, there needed to be a continuous and reliable flow of information about the target region. The forms of communication were very diverse: a central element was made up of verbal or written transmission of knowledge about opportunities for employment, education, marriage, or housing by previous (pioneer) migrants who had already gone out there, whose reports were given greater weight on the grounds of connections of family relationship or acquaintance. There was however also the phenomenon, albeit rare, that the first settlers deliberately kept quiet about problems with the aim of overcoming these by attracting more of their friends and relatives to come out to the new homeland. Reliable and adequate sources of information affecting the genesis and the implementation of the decision to emigrate were predominantly only available to the potential migrants for one particular target location, or for individual settlements limited to a local area, or to specific segments of the employment or education market, so that realistic options for making choices between different target areas could not have been made available.