acknowledgments

First I would like to thank my wife, Elizabeth Lankford, who has always been my first reader. She remained enthusiastic about Rudolph, even while living with year-round Christmas for the duration of this project. I also appreciated my correspondence with author Tim Hollis. Tim kindly shared his own knowledge of Rudolph while providing several key pieces of research.

A number of people at college and public libraries also aided my research: Peter Carini and Joshua Shaw at the Rauner Library at Dartmouth; Stephanie Hunter and Winston Barham at the University of Virginia Music Library; Belinda Carroll at the Knight-Capron Library at Lynchburg College; Jeannie Isaacs at the Campbell County Library in Rustburg, Virginia; Lesley Martin at the Chicago History Museum; Amanda Stow and John R. Waggener at the American Heritage Center; Elizabeth Dunn at Duke University; Janet C. Olsen at Northeastern University Library; and George Willeman with the Library of Congress. For everyone else I corresponded with and for those who generously provided images for the project, thank you.

I would like to thank both Bronwyn Becker at the University Press of New England and Glenn Novak. I would also like to thank my agent, Robert Lecker, for his help with developing and finally placing this book project.

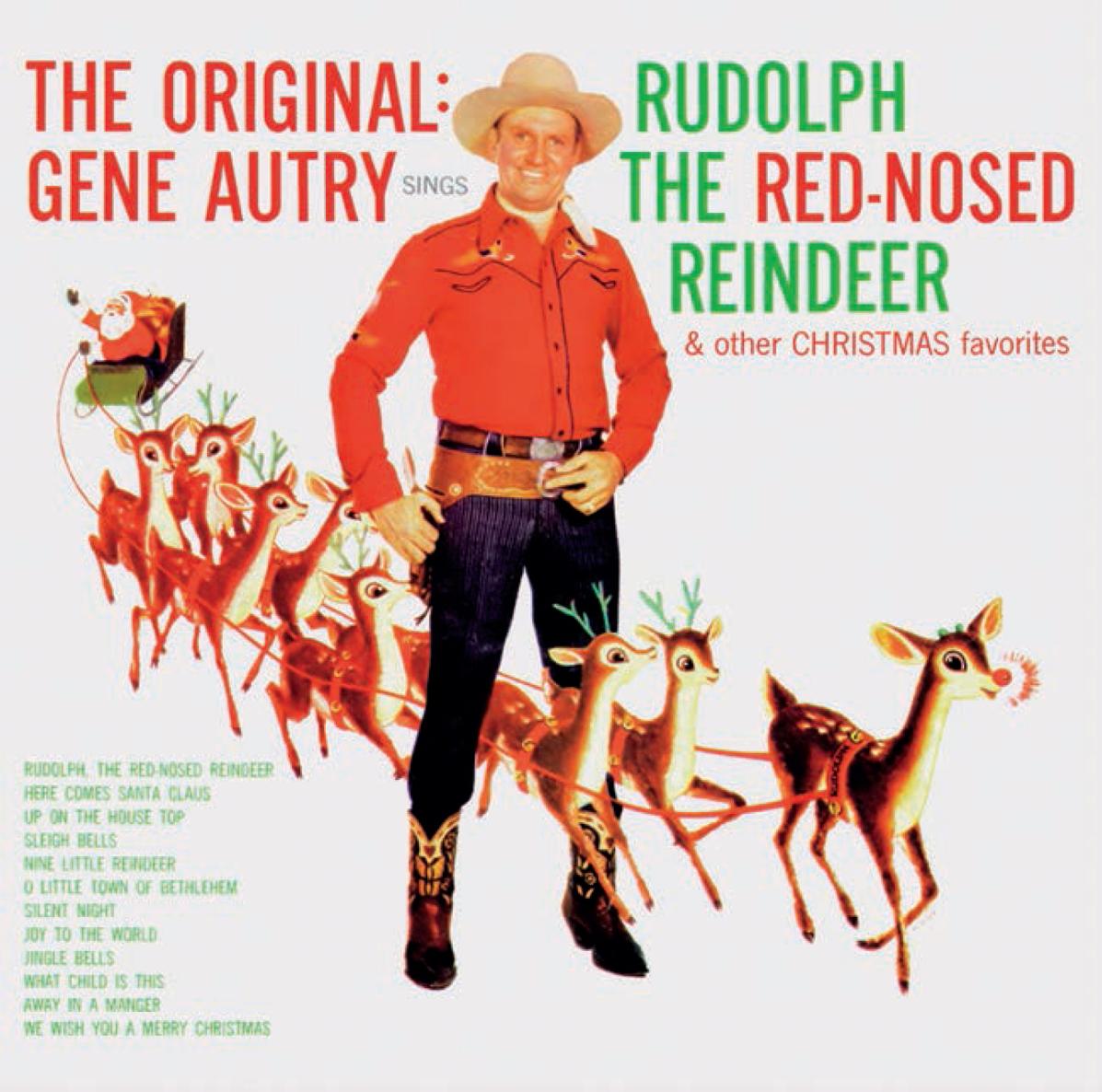

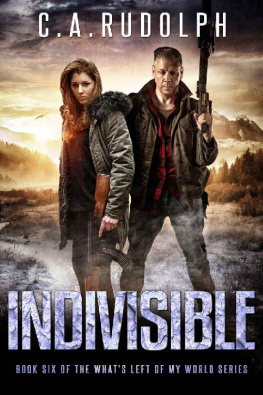

Gene Autry, Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, 33 album (Challenge, 1957)

introduction

RESEARCHING RUDOLPH

As a kid I remember listening to Gene Autry sing Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer dozens of times each Christmas. It was the late 1960s, and I lived with my parents and a younger brother and sister in Norfolk, Virginia. Christmas was a big deal. We helped Mom decorate the tree, with reflectors behind those big, primary-colored bulbs. She never let us touch the tinsel, since wethe kidstended to throw it in clumps on the white pine. There were also cherry cookies and Christmas spice cake. Dad decorated the picture window in the living room, drawing Christmas scenes with white shoe polish, and drew a smaller scene on the bathroom mirror. And in the background, through whatever we were doing, Christmas songs and carolsthe Lennon Sisters, Johnny Mathis, and Chet Atkinsalways played. Rudolph, though, was the best. Without him, I believe, Christmas would never have been complete.

The Autry album we played was called Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer and had been issued by Autrys very own label, Challenge, in 1957. This was back when marketing folks went to a lot of trouble to create an arresting image for a 33 album cover. I was fascinated by the picture of Autry, dressed as a giant cowboy, with Santas sleigh and the reindeer team flying underneath his legs. This Rudolph was not the original: the original song had been recorded by Autry for Columbia in 1949. But it was the only version we knew, and the album had the added bonus of a second Rudolph song, Nine Little Reindeer. My brother and I preferred the first side of Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer with all the Santa and Rudolph songs, as opposed to the carols on side two.

What strikes me now is how much we accepted Rudolph as a part of our traditional family Christmas. Rudolph seemed, in song (1949), in the Little Golden Books version of Robert L. Mays story (1958), and in the Rankin/Bass animated TV special (1964), as much a part of our Christmas celebration as Santa Claus and all the lorethe elves, the North Pole, Mrs. Claus, and the other eight reindeerthat went with him. Santa Claus, however, could be traced back in a somewhat recognizable form for a hundred years. Rudolph, a sacred part of our familys holiday tradition, could be traced only to 1939. From the standpoint of 1969, Rudolph could hardly qualify as a central myth of an American Christmas, but we did not know that. Likewise, while Rudolph could hardly qualify as genuine folk culture, wealong with millions of othersaccepted him as such.

I never planned to write a book about Rudolph. He was so much a part of my childhood, so much a part of the kind of Christmas I had grown up with, that I just accepted him as having always been there. It did not occur to me that Rudolphthe modest hero with a secret resourcereflected deeply held American values.

My innocence about the connection between Rudolph and our holiday values started to change a couple of years ago when I was writing about American Christmas songs. One of those songs, naturally, was Johnny Markss Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. As I began researching, several things occupied my thoughts. Rudolph, as James H. Barnett noted in 1954, was the only new addition to our Christmas lore in a hundred years. While Barnett wrote this in the 1950s, it remains true: as much as we love Frosty and other Christmas critters, none of them have become as central as Rudolph. The truth of this, though, fails to explain why Rudolph was accepted into Christmas lore so quickly. Likewise, it fails to explain how Rudolphs image has remained expansive enough to speak to Americans acrossas I write thisseven decades.

The origin of Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer also fascinated me. Many people, listening to the song or watching the 1964 cartoon, had completely forgotten Rudolphs origins as a promotion in 1939 and 1946 for Montgomery Ward. Unlike Santa Claus, Rudolph had no European folk myths to draw from. Instead, he was born in the imagination of copywriter Robert L. May, who was employed by Montgomery Ward. The idea was simply to give away thousands and thousands of copies of Rudolph, in booklet form, at Wards six-hundred-plus stores to children accompanied by a parent, drawing the family into the department store for the all-important holiday season. Merchandise, the same kind that accompanies any Disney movie promotion today, would follow.

Despite these commercial origins, children and even parents accepted Rudolph as though he were the genuine article. Folklorists could label the Jolly Green Giant fakelore or use the term industrial folklore to define the Trix rabbit, but childrenlearning about the reindeer in books, View-Master reels, a game, a cartoon, in song, and multiple pieces of merchandiseseemed oblivious to academic concerns. Clearly, Robert L. May wrote Rudolph in 1939; equally clear, he wrote Rudolph at the request of his supervisor as a work-for-hire at Montgomery Ward. Likewise, a popular groundswell greeted Rudolph on his introduction in 1939 and reintroduction in 1946; this groundswell was heightened considerably, however, by Montgomery Wards giveaway of six million copies of the Rudolph booklet. While we can argue whether commercial or creative forces exerted more influence over Rudolphs growth in popular culture, both had a role to play. Rudolphs grounding in both commercial and folk culture produced, I believe, an intriguing paradox worth looking into.