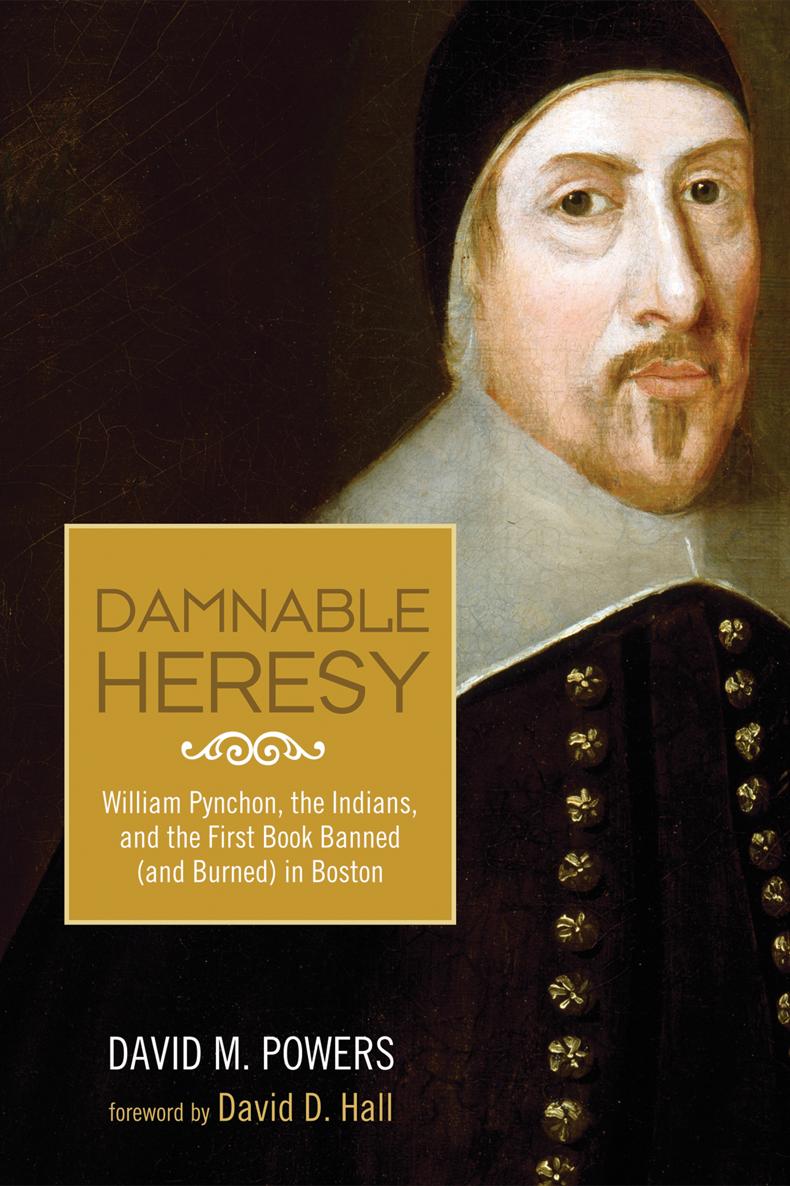

Portrait of William Pynchon. Used by permission of the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts.

Damnable Heresy

William Pynchon, the Indians, and the First Book Banned (and Burned) in Boston

David M. Powers

Foreword by David D. Hall

Damnable Heresy

William Pynchon, the Indians, and the First Book Banned (and Burned) in Boston

Copyright 2015 David M. Powers. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical publications or reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publisher. Write: Permissions, Wipf and Stock Publishers, W. th Ave., Suite , Eugene, OR 97401 .

Wipf & Stock

An Imprint of Wipf and Stock Publishers

W. th Ave., Suite

Eugene, OR 97401

www.wipfandstock.com

isbn 13: 978-1-62564-870-9

eisbn 13: 978-1-63087-761-3

Manufactured in the U.S.A.

To the memory of my teachers,

George Huntston Williams

C. Conrad Wright

Foreword

B e it as founder of a Massachusetts town or be it as lay theologian, William Pynchon ( 1590 1662 ) complicates the stories we like to tell about the Puritan founders of New England in the seventeenth century. He is in good company, for the complexities of his life were repeated many times over among the people who chose to come to New England in the s. How can we weave so many strands of thought, action, and identity into a single narrative that encompasses entrepreneurs and idealistic theocrats, the heterodox and the orthodox, the English and the Native Americans, local circumstances and what was happening in the Atlantic world? From day one, the organizers of the Massachusetts-Bay Company ( 1629 ) were acutely aware that every step they took was being scrutinized in England by their enemiesand for that matter, by their friends. Were they friends or foes of the government of the English monarch Charles I? Were they so critical of the Church of England, the state church to which all of them officially belonged, that they were really Separatists (the most radical wing of the Puritan movement)? From day one, the organizers of the Massachusetts-Bay Company, with John Winthrop at its head, struggled to control an untidy process of emigration and settlement that disrupted their initial plans for where people would live. And, from day one, the ambition of many of the colonists to create pure churches on this side of the Atlantic brought into play all of the contradictions that had developed within the Puritan movement since its beginnings in the middle of the sixteenth century. Should local congregations be generously inclusive, or admit only those who were visible saints? Should local congregations defy the civil state, or allow it to regulate some aspects of religion? Should lay people be allowed to speak out on matters of theology, or must they defer to the expertise of university-educated ministers? Behind these questions lay the challenge of creating a consensus strong enough to keep the new society from falling apart, as had happened at Jamestown in the Chesapeake.

There is much to learn from the life of William Pynchon as David Powers has reconstructed it, for Pynchon sat astride several of the forces that could have wrecked the Puritan colonies. He reached out to the Native Americans and was notably fair in his dealings with them; his skills as a merchant and fur trader helped the colonists find their footing, but not at the price of giving up religion; he supported Winthrop and other magistrates in their efforts to keep the lid on religious and social dissent; and when, as a lay theologian, he speculated about a fairly abstruse point of doctrine and got into trouble for doing so, he never repudiated other aspects of mainstream theology. No wonder, then, that historians have disagreed on how to locate him within the wider story of Puritan New England. Now, in this new biography, we can see more clearly than ever before that Pynchon was not as much of an outlier as others have suggested. Here, for the first time, we are provided the fullest possible account of Pynchons activities as a Puritan and entrepreneur before he emigrated and after he returned to England. And here, we see him as a man of the Atlantic world. So were many of the colonists who remained in New England, and the alarm bells that went off in Boston about Pynchons theology are best seen as a response to Atlantic circumstancesin particular, the extraordinary proliferation of heterodox or divergent theologies among lay people (and some clergy) in Civil War England. In the 1640 s, the leadership in Massachusetts had been singed by accusations from abroad that their system of congregational governance was responsible for much of the turmoil in England. Taking a stand against Pynchon was part and parcel of a program intended to demonstrate to English and Scottish Puritans that, on the contrary, orthodoxy was in good hands in New Englandindeed, faring better in New England than in their homeland.

Much that is unexpected awaits the careful reader of Damnable Heresy. We may still feel challenged by the presence of someone as distinctive as Pynchon, but we finally have a full telling of his life on which to base any larger narrative.

David D. Hall

Bartlett Research Professor of New England Church History

Harvard Divinity School

Acknowledgments

I could not have brought my Project Pynchon to this completion without the assistance of many others. My deep thanks for their expertise, encouragement, and willing help in so many ways go to:

David D. Hall, Bartlett Research Professor of New England Church History, Harvard Divinity School, always unfailingly supportive and generous with encouragement, wisdom, and advice;

Glynis Morris, Archive Assistant, Deputy Librarian at the Essex Record Office, Chelmsford, United Kingdom ( 19942014 ), and researcher extraordinaire;

Margaret Bendroth, Executive Director of the Congregational Library and Congregational Christian Historical Society, Boston, Massachusetts, and an ever-dependable advisor;

Maggie Humberston, Head of Library and Archives, and Cliff McCarthy, Archivist, Lyman and Merrie Wood Museum of Springfield History, Springfield Museums, Springfield, Massachusetts, who provided ready access to original sources;

Margaret Baker of Brentwood, Essex, United Kingdom, translator of the Latin record of William Pynchons fealty at the Springfield Dukes manorial court in 1622 ;

Raymond John Brown, Rector of All Saints Church, Springfield, Chelmsford, United Kingdom;

Simon Douglas Lane, Vicar of St. Andrews Church, Wraysbury, United Kingdom ( 2005 2013 );

Dennis Pitt, historian, Wraysbury, United Kingdom;

Barbara Wells, Assistant Librarian, Dennis Memorial Library, Dennis, Massachusetts;

Linford D. Fisher, Assistant Professor of History, Brown University;

Kevin McBride, David Naumec, and Laurie Pasteryak Lamarre of the Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center, Mashantucket, Connecticut;

Gloria Korsman, Research Librarian, Andover Harvard Library, Harvard Divinity School;