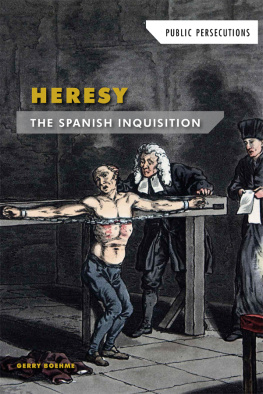

The Spanish Inquisition finally ended under the reign of Queen Isabella II.

FIVE

Aftereffects

H ow and why did the Spanish Inquisition end?

The French abolished the Inquisition in 1808 after they occupied Spain. Traditionalists in Spain pressured King Ferdinand VII to restore it in 1814, but by then it was fairly inactive. Progressive opposition won out a second time in 1820, and the Inquisition was again abolished. Finally, on July 15, 1834, Queen Isabella II issued the final decree of suppression. The Spanish Inquisition was finally over, although by that time the decree was just a formality.

Queen Isabella started the Spanish Inquisition way back in 1478. Ironically, almost 360 years later, it was ended by her namesake, Isabella II, who once and for all rid Spain of its cruel practices.

While history may tell us that the French invasion, the Protestant Reformation, or the Age of Enlightenment helped to end the tribunals, two other powerful forces played perhaps an even more important role.

A shift in popular attitudes, combined with simple economics, finally put a halt to the Spanish Inquisition.

Losing Interest

After more than three centuries of terror and misery, the people of Spain simply started to lose interest. By the end of the seventeenth century, the pageantry of the auto de f no longer held the same appeal for the masses. People became indifferent to the all-day event.

This change of opinion was certainly influenced by what Spaniards heard about themselves from other countries. As Spain stubbornly held on to its Inquisition, the kingdom was ridiculed throughout the rest of Europe. French philosophers like Voltaire portrayed Spain as a relic of the Middle Ages authoritarian, intolerant, ignorant, and barbaric. Writers, philosophers, and artists railed against the cruelty and unfairness of the inquisition, as well as its accompanying censorship that cracked down on different ideas and new ways of thinking. As independent thought and religious tolerance continued to spread across Europe, popular support for inquisitions, both Catholic and Protestant, withered.

Putting the historical times in perspective, the last execution by the Spanish Inquisition occurred fifty years after the signing of the American Declaration of Independence. Unlike some European governments that still believed it was possible to stamp out heresy and control their people through religion, one of Americas guiding principles preached just the opposite: separate the church from the state and permit all citizens to practice religion in their own way. As different Protestant denominations continued to multiply in northern Europe, and as Europeans learned more about the United States and its beliefs, inquisitors and their supporters were forced to realize that the rise of new religions and ways of thinking was unstoppable.

Fewer Victims Meant Less Money

In a manner of speaking, the tribunals also became victims of their own success. They did such a good job of eliminating heretics that it was difficult for inquisitors to find more people to persecute. Fewer victims meant fewer penalties, and that meant there was less money and property to be confiscated to pay for the rising costs of the Inquisition.

With less wealth and fewer people to persecute, the Suprema began to lose its influence. Spains war with France weakened the Inquisition even further. The government sold off some Inquisition assets, such as property, to finance the war, and many agents of the tribunals were summoned to serve in the army, ending their life of privilege beyond the governments control.

Echoes of the Black Legend

Eventually, the Spanish Inquisition collapsed under its own weight. Now came the time for the era to be put to rest and the judgments of history to begin.

As time passed, many records of the Inquisition were lost or destroyed by Joseph Bonaparte and others. As propaganda in favor of the tribunals mixed with propaganda promoting the Black Legend, it became increasingly difficult for historians to determine with any certainty what exactly happened or did not happen during the Spanish Inquisition.

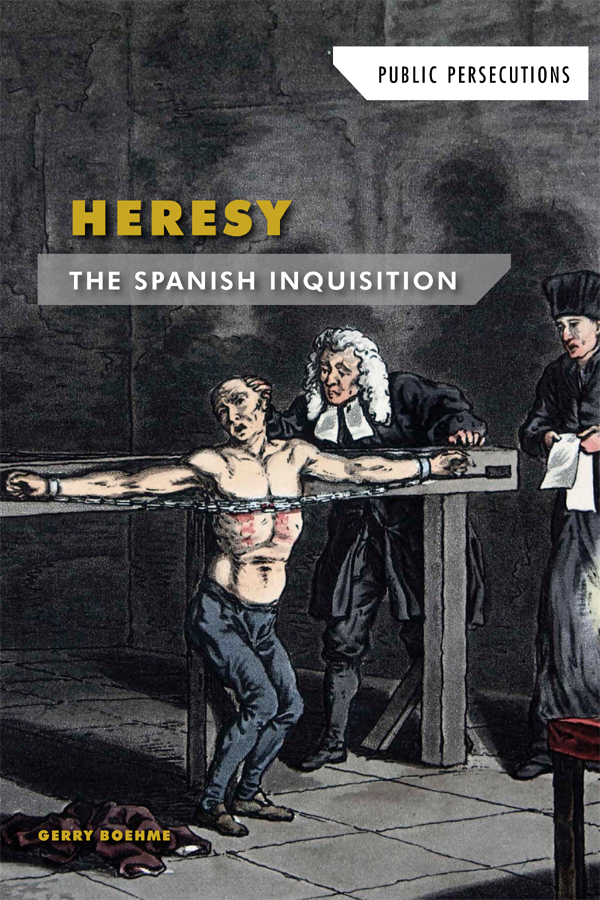

Painters and writers who opposed Spain and the Catholic Church exaggerated the real horrors for their own purposes.

Some of the researchers approached the subject with predetermined opinions and biases, committed to presenting a particular point of view rather than to consider all the facts. Perhaps they wanted to defend Spain and the Catholic Church, or they wanted to speak out for the victims who were unjustly targeted and punished. Maybe they simply wanted to attack Spain and the Catholic Church for political or religious reasons. No matter what their intent, authors and artists found plenty of material they could use to support whatever point of view they set out to portray. Their efforts served to further darken the already muddy waters surrounding the conduct of the tribunals.

History Revised

Fortunately, recent discoveries and the release of new information sources have made it easier for historians to construct a much more accurate and honest account of what actually occurred during the nearly 360 years of the Spanish Inquisition. The past 40 years, in particular, have witnessed the development of what is called a revisionist school of Inquisition history, a controversial area where the aim is to re-examine the traditional history of the tribunals.

Two extensively detailed books Inquisition, written by Edward Peters in 1988, and The Spanish Inquisition: A Historical Revision, written in 1997 by Henry Kamenstrived to use newer sources to more accurately portray what really happened during those times.

Kamens book is especially noteworthy. He had previously written a well-respected history of the Spanish Inquisition back in the 1960s. New information had become available since he wrote it, however, and he felt the responsibility to examine his earlier conclusions. What he discovered led him to publish a major revision, and call it as such, more than thirty-five years later. In the preface to his revision, Kamen writes, Very much [in his previous book] has been superseded by subsequent research. Thanks to the quality of work over these years by specialists, it is now possible to get a far more reliable image of the Holy Office of the Inquisition. In many key respects, consequently, I have been obliged to change my views.

Vatican Opens the Archives

In 1962, Pope John XXIII summoned about two thousand bishops for the Second Vatican Council. The council acknowledged many unhappy chapters of Christianitys past relations with other religions, noting past quarrels and hostilities, and urged all ... to strive sincerely for mutual understanding. Since that time, even more information about Catholic Church inquisitions has come to light.

Perhaps most importantly, the Vatican finally opened up its own private archives for historical investigation. In 1998, Pope John Paul II granted access to the archives of the Holy Office (the modern successor to the inquisitions), which were previously shrouded in mystery and hidden from public view, and invited thirty scholars from around the world to attend a three-day symposium. The discussion would concentrate on the historical background of all the persecutions that began back in the thirteenth century and continued until the Spanish Inquisition ended in 1834.