Published in 2017 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC

243 5th Avenue, Suite 136, New York, NY 10016

Copyright 2017 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC

First Edition

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwisewithout the prior permission of the copyright owner. Request for permission should be addressed to Permissions, Cavendish Square Publishing, 243 5th Avenue, Suite 136, New York, NY 10016. Tel (877) 980-4450; fax (877) 980-4454.

Website: cavendishsq.com

This publication represents the opinions and views of the author based on his or her personal experience, knowledge, and research. The information in this book serves as a general guide only. The author and publisher have used their best efforts in preparing this book and disclaim liability rising directly or indirectly from the use and application of this book.

CPSIA Compliance Information: Batch #CS16CSQ

All websites were available and accurate when this book was sent to press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

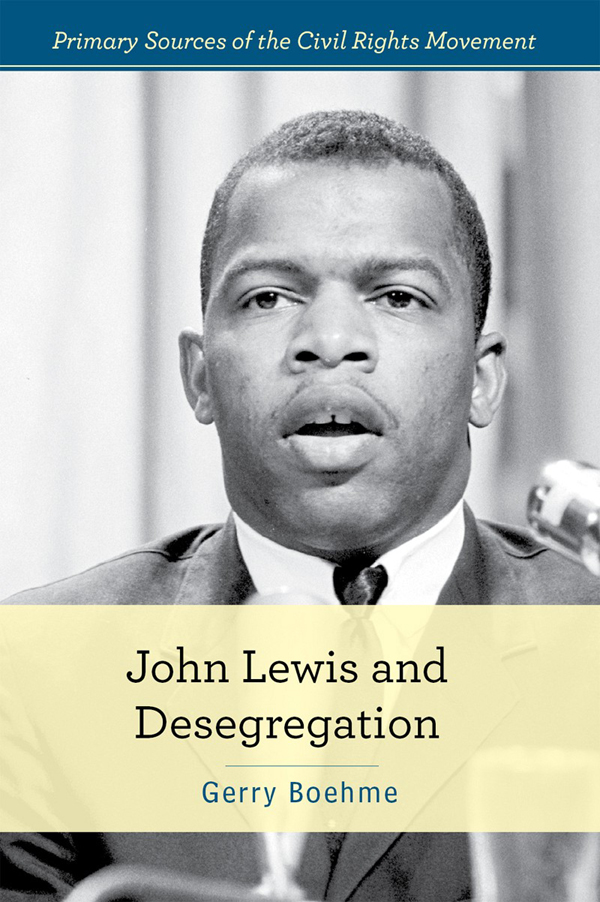

Names: Boehme, Gerry.

Title: John Lewis and desegregation / Gerry Boehme.

Description: New York : Cavendish Square Publishing, 2017. | Series: Primary

sources of the civil rights movement | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016003672 (print) | LCCN 2016006765 (ebook) |

ISBN 9781502618689 (library bound) | ISBN 9781502618696 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Lewis, John, 1940 February 21---Juvenile literature. |

African American civil rights workers--Biography--Juvenile literature. |

Civil rights workers--United States--Biography--Juvenile literature. |

African American legislators--Biography--Juvenile literature. |

Legislators--United States--Biography--Juvenile literature. | African

Americans--Civil rights--History--20th century--Juvenile literature. |

Civil rights movements--Southern States--History--20th century--Juvenile literature.

Classification: LCC E840.8.L43 B64 2017 (print) | LCC E840.8.L43 (ebook) |

DDC 328.73/092--dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016003672

Editorial Director: David McNamara

Editor: Fletcher Doyle

Copy Editor: Nathan Heidelberger

Art Director: Jeffrey Talbot

Designer: Amy Greenan

Production Assistant: Karol Szymczuk

Photo Research: J8 Media

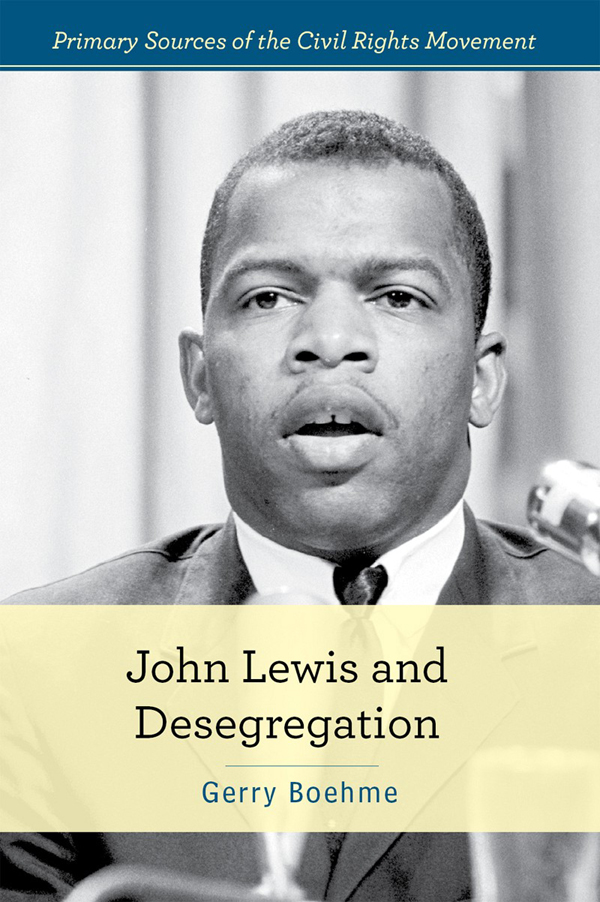

The photographs in this book are used by permission and through the courtesy of: Marion S. Trikosko, U.S. News and World Reports/Library of Congress/ File:John Lewis 1964-04-16.jpg/Wikimedia Commons, cover; William Lovelace/Express/Getty Images, .

Printed in the United States of America

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Equality and the Right to Vote

CHAPTER ONE

An Activist in the Making

CHAPTER TWO

The Fight for Rights

CHAPTER THREE

The Pinnacle of the Civil Rights Movement

CHAPTER FOUR

Pointing the Way to Freedom

INTRODUCTION

Equality and the Right to Vote

T he United States was founded upon the promise of freedom and equal rights for all. One of those rights was the ability to choose leaders who would serve all citizens.

When the American colonies claimed their independence from Great Britain in 1776, the second paragraph of their Declaration of Independence declared that:

all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government.

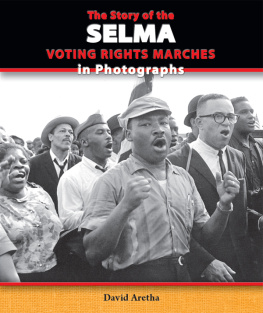

American civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. walks with his wife, Coretta, while leading a march for equal voting rights in Alabama in March 1965.

At the time, the message seemed clear. Men are equal. Their rights, granted by a higher power, include freedom and the pursuit of a good life. A government draws its power from the citizens it is meant to serve. And, if the government fails in its mission, the people have a right to change it.

Unfortunately, right after the Declaration of Independence was signed, the debate began. Did all men include all people, or just men but not women? Did all really mean all, or just whites, to the exclusion of blacks, Native Americans, and other people of color?

Like many other countries at that time, the American colonies practiced slavery. Some of the men who signed the declaration believed that allowing slavery directly contradicted the idea of liberty. Others disagreed, especially those from the Southern colonies. Some owned slaves themselves and depended on the free labor that slaves provided. Some also felt deep racial and considered slaves to be property, not human beings.

Just eleven years later, the United States Constitution guaranteed citizens the right to vote, but each state was allowed to decide who could actually cast a ballot. While the requirements varied from one state to the next, all states allowed only white adult males to vote. African-American menand all womenwere excluded.

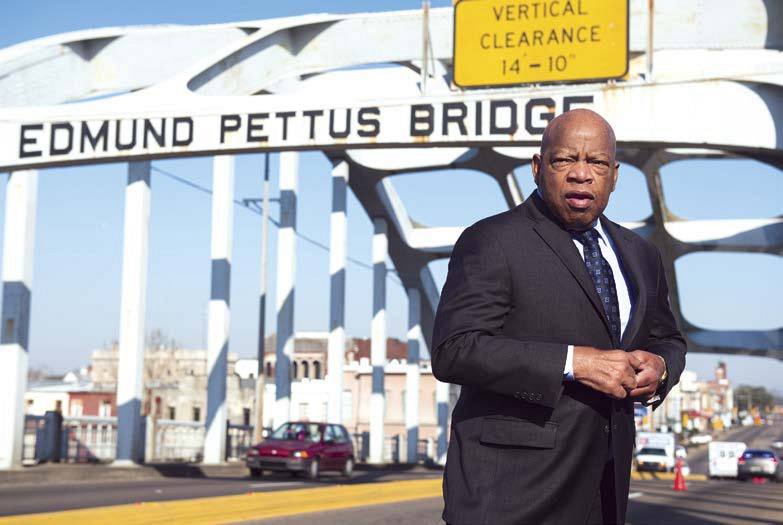

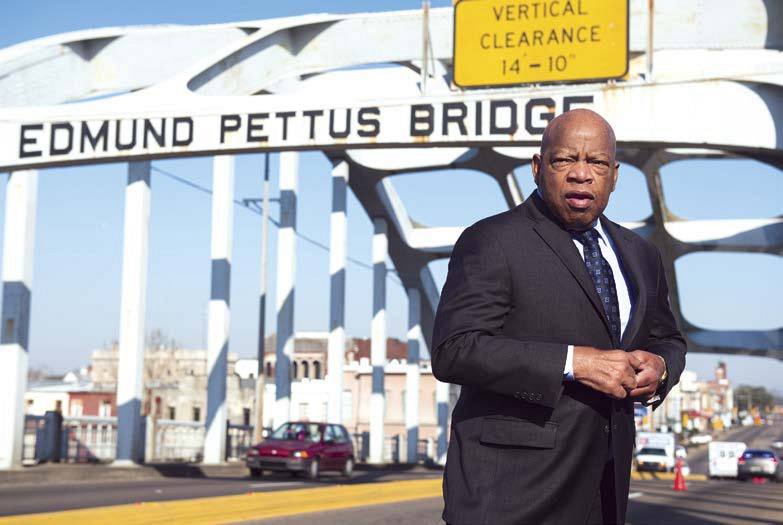

Congressman John Lewis stands on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, fifty years after he and other civil rights marchers were viciously beaten by state troopers.

When the Civil War ended and slavery was abolished in 1865, the US Congress passed three constitutional amendments that guaranteed blacks freedom, citizenship, and the right to vote. In addition, two new acts (passed in 1866 and 1875) gave blacks more legal rights and outlawed discrimination based on a persons color in public transportation, facilities, and restaurants.

Southern states were still determined to limit the rights of black Americans, however. White Southerners passed laws that separated whites from blacks and made it difficult for African Americans to vote. For the next hundred years, the people of the movement fought in a life-or-death struggle against those opposed to equal rights for African-American citizens. The battle was filled with stories of bravery and dedication, suffering and sadness, faith, hope, and victory.

John Lewis joined that struggle as a young man in the early 1960s. He quickly became one of the most important leaders of his generation.

CHAPTER ONE

An Activist in the Making

F amous civil rights leader and congressman John Lewis was born on February 21, 1940, outside of Troy, Alabama. Troy was a small city in Pike County, an area known for its rich farmland. Pike Countys population was only about thirty-two thousand when Lewis was born, and about half the people living there were African American. Typical for that time, most white people lived in or near the town, while most African Americans lived in the rural areas outside of town.

Happy but Poor

Lewiss parents were three of his brothers. Early in his life, the only book in his home was the Bible.

Next page