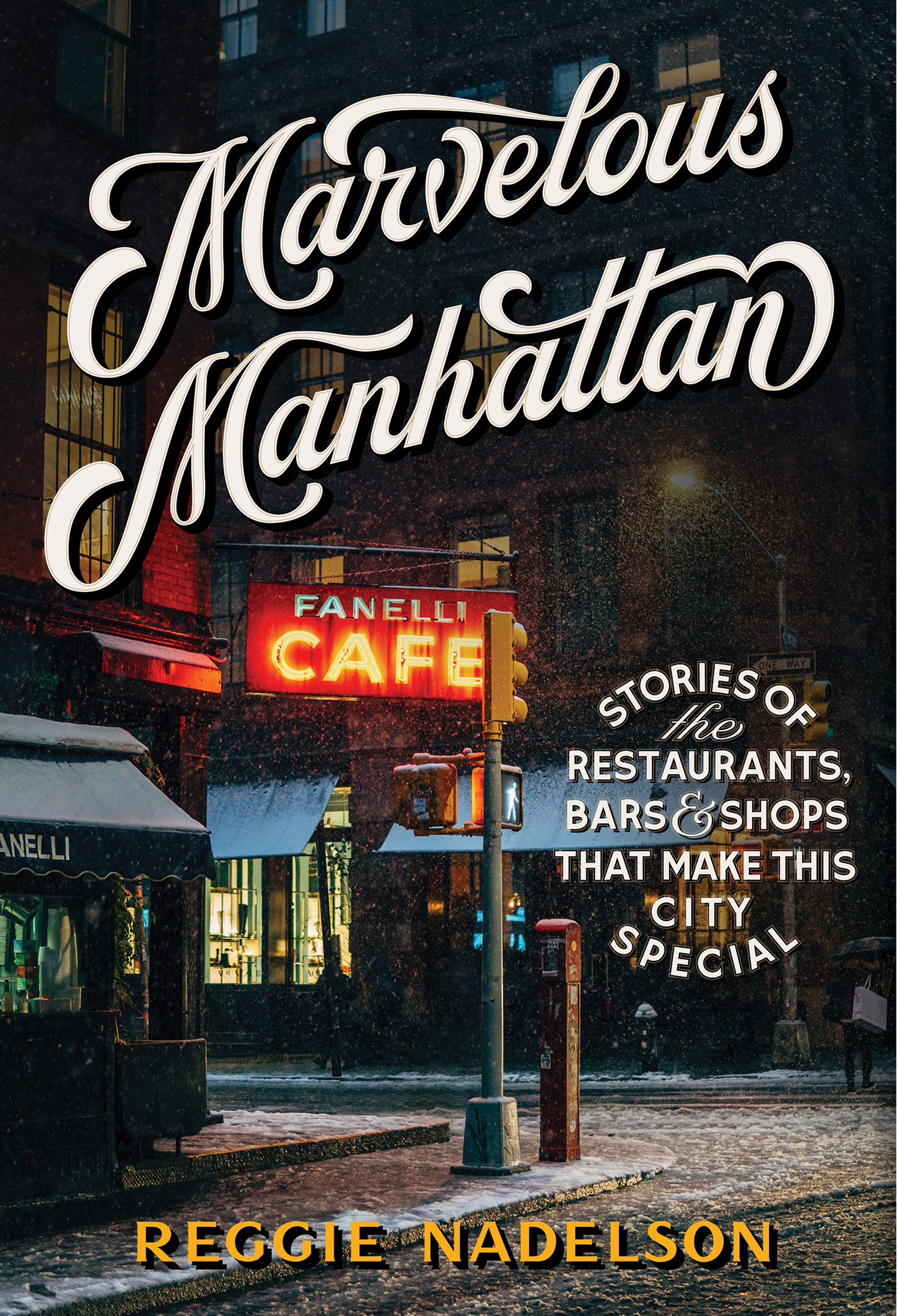

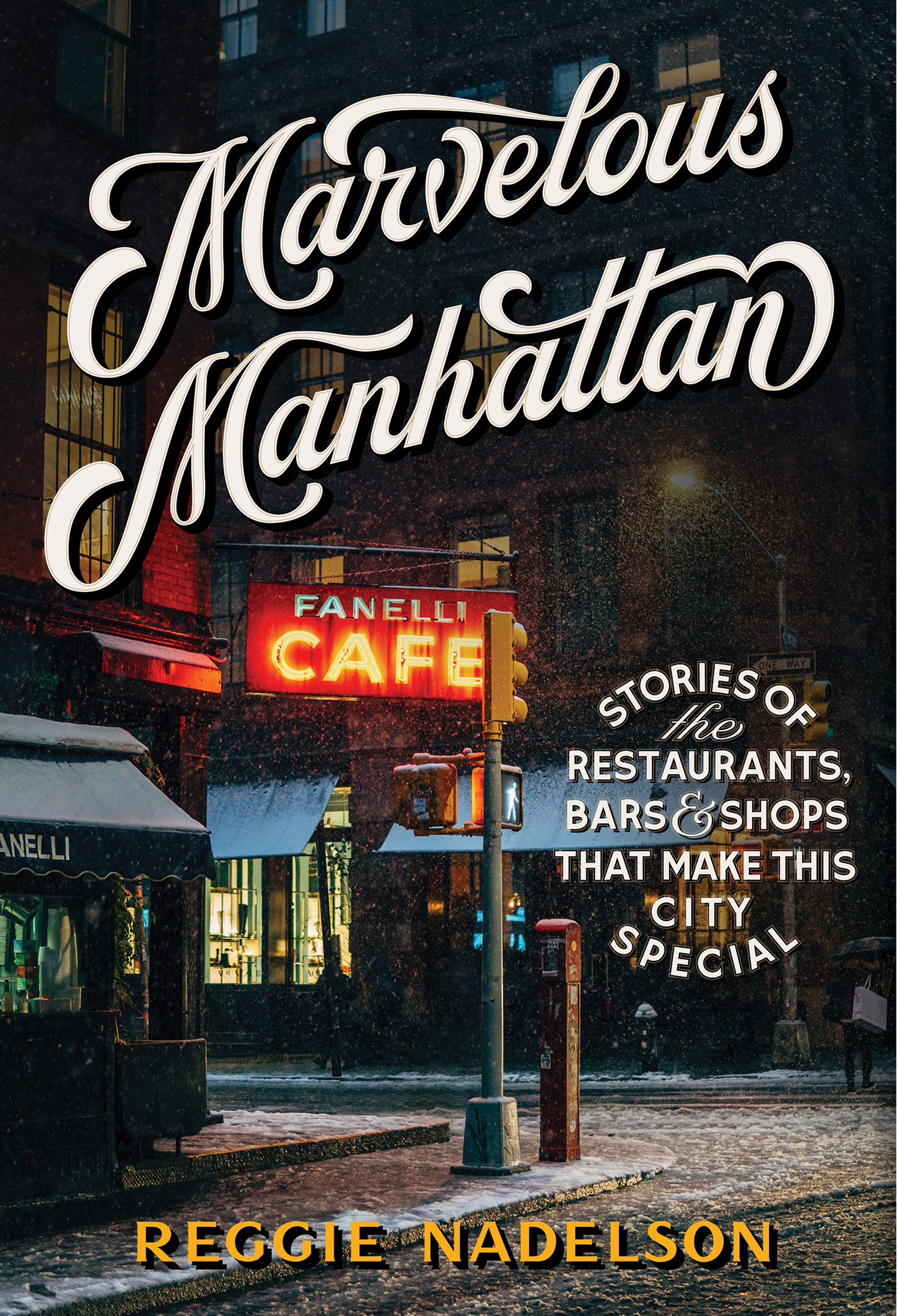

stories of the restaurants, bars & shops that make this city special

Reggie Nadelson

Artisan New York

For Leslie Woodhead, a true New Yorker

I came to New York and in only hours, New York did what it does to people: awakened the possibilities. Hope breaks out.

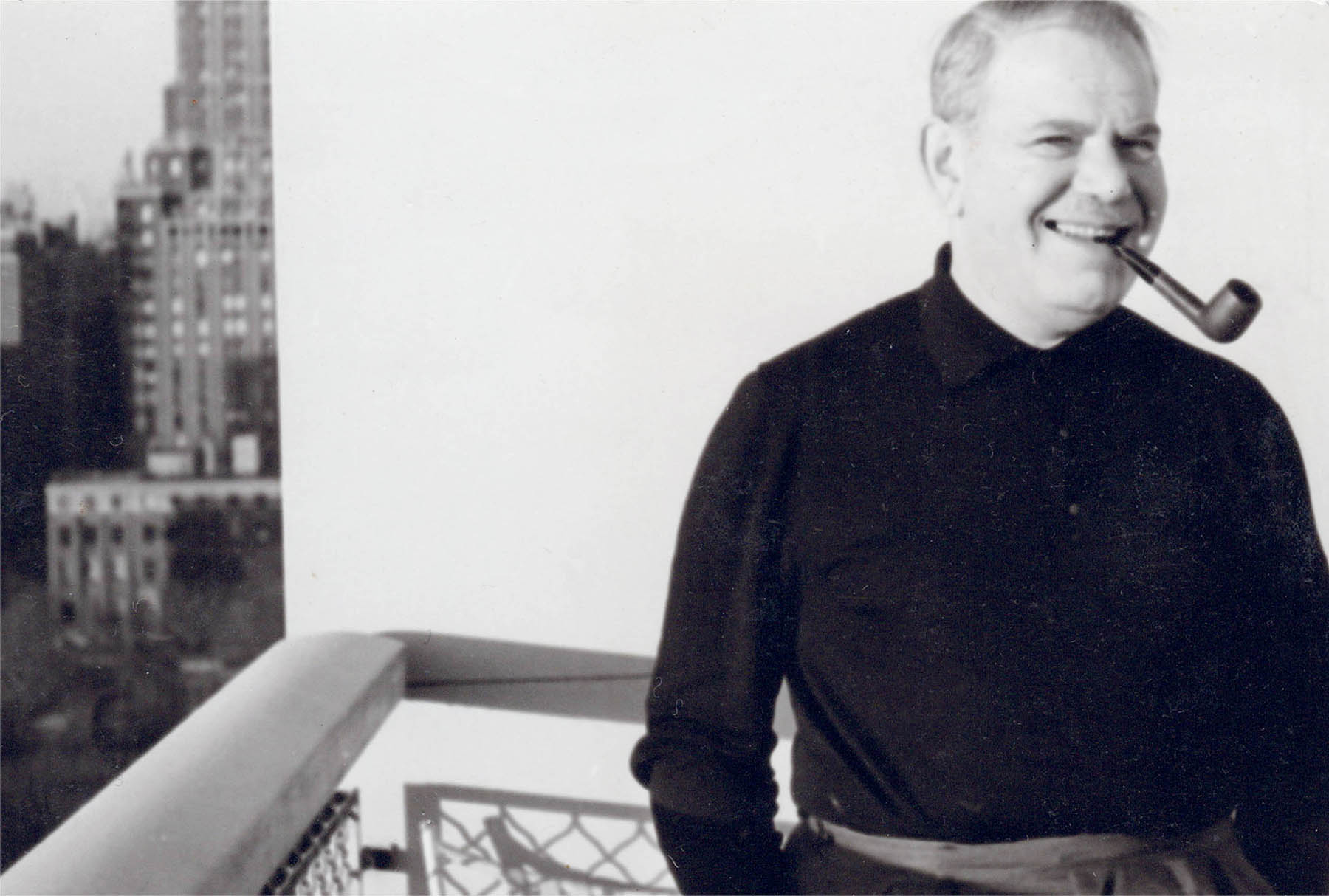

Philip Roth

Contents

left to right : My aunt Shirley Panzer; my mother, Sally; and my godmother, Regina Senz, between acts at the Met.

Preface

My Mothers New York

I n 1925, when she was seventeen, my mother got the train from Winnipeg to New York.

You hear that whistle, darling? Sarah would say to her little sister, Jeanette. Thats the Canadian Pacific Railway, and one day Im taking it to New York City. And she did, and almost from her arrival, the city was everything she had imagined.

In 1935, she filed naturalization papers that led to U.S. citizenship. In the document (where Sarah became Sally, a hipper, seemingly more urban moniker), as required, she forswore other allegiances, national or royal. In her heart, though, her true fealty was to New York City. She became one of E. B. Whites settlers.

In his 1949 book Here Is New York, the wonderful twentieth-century writer says that there are three New Yorks: Commuters give the city its tidal restlessness; natives give it solidity and continuity; but the settlers give it passion. He adds that, of these three cities, the greatest is the lastthe city of final destination, the city that is a goal. The settler embraces New York with the intense excitement of first love, and absorbs New York with the fresh eyes of an adventurer.

My mothers fierce need to get to New York was driven by her ambition to become somebody else, tolike so many young womenlive a freer, different life, away from the provinces, places of hidebound convention. New York appeared a shining city, flashing its lights shamelessly at you, a place where you could disappear, hide from your old self, create a new one.

As soon as she arrived, my mother joined the Communist Party and the Lucy Stone League, a group of early radical feminists. She shopped at Loehmanns, went to speakeasies like 21, to Connies Inn in Harlem to see Louis Armstrong, to the Cherry Lane Theatre for avant-garde plays. I remember your mother so well, says Jane Mushabac, my best friend in the Greenwich Village building where I grew up. She had a mink coat, and your father wore a beret. She had been a Communist, which was fairly sophisticated; she drank martinis and was very stylish. Her favorite word was stunning, and she taught my mother about opera.

Stunning. My mother and her sister, who had moved to New York and was now calling herself Shirley, spoke to each other sometimes in Yiddish but more often using the hyperbolic lingostunning, divine, marvelousof characters in a Nol Coward play (or Billy Crystals homage to Fernando Lamas on SNL). To them, Manhattan was indeed marvelous. Many years later, Shirley, a newspaperwoman, would buy me my first martini at the Plaza.

Its 1939. Sally and my father, Sam, have moved to that Village apartment at 21 East 10th Street, where I would later be raised. Standing at the window in the new apartment, she looks across the street to the Hotel Albert caf with its blinking red Eiffel Tower, then leans out as far as she can, takes note of the bars, galleries, bookshops, secondhand furniture stores, and of the skyline on the horizon. She felt then, as she always did, that New York was the gold ring.

For a couple of years now, Ive been writing a column about the city for T Magazine at the New York Times. This book is based on those columns, but its only now as Im putting it together that I can see just how much my mas feeling for the city rubbed off on me.

The column was given its title, The 212, by the writer Salman Rushdie, an old friend of mine and, like my mother, a settler. 212 was the original Manhattan area code. People hang on to it as if giving it up means losing some singular status. Very few cities cling to their myths or their history the way New York does; even as it hurries to tear things down, to build up bigger, higher, richer, there is always that rueful melancholy for the past.

In the Times, my column is described this way: Reggie Nadelson revisits New York institutions that have defined cool for decades, from time-honored restaurants to unsung dives. Most of the places I love are one of a kindindependent bookshops, mom-and-pop cafs, corner bars. They are often run by second, third, fourth, even fifth generations of a family. At Schaller & Weber, Jeremy Schaller serves up great German sausage with his grandfathers passion for it. There is still good music at Mintons Playhouse in Harlem, where Thelonious Monk, Charlie Parker, and Dizzy Gillespie invented bebop in the 1940s. Niki Russ Federman is the fourth generation to run Russ & Daughters, the appetizing shop. After college, she went to work in the art world, but like her father, Mark Federman, she came back to Russ. Mark always says he heard the call of the lox. Time-honored, indeed.

Unsung dives are harder to find in a city where everyone is crazy to be first, to be in the know, to find that secret restaurant without a sign outsidelike Indochine once wasindicating that if you cant find it, you dont belong. You imagine youve located a wonderful little-known Hungarian pastry shop near Columbia, only to hear from old friends that they frequented it in their college days.

Cool is something else. New York thinks it invented cool, although it was in fact Lester Young, the great saxophonist from Mississippi, who is thought to have originated the term around 1933, even before the Village Vanguard, where he played, opened.

My mother was pretty cool. She had unerring taste, though God knows where a girl from Winnipeg got it, how she knew where to shop in an age without internet. She worked as a nurse, but if a Chanel showed up in the Back Room at the original Loehmanns in Brooklyn, she found it. She shopped at stores on University Placegrocer, fishmonger, shoemaker, florist (who is still there). She was friends with the bookseller on 10th Street, went for lunch alongside Village artists at the now long-gone counter at Bigelows drugstore. I never asked her how she knew her way around. It was if she had a map of Manhattan imprinted on her heart. (I never asked anything much, for that matter, and that is part of the sadness of losing a parent; once the grief wears off, you feel a poignant sorrow that you never asked. You get the blues.)

Next page