Preface

As the eighteenth century came to an end, thoughtful Americans like Thomas Jefferson and the Reverend Samuel Miller gravely pondered the role that their countrymen had played in the brilliant achievements of the Enlightenment. Almost pathetically they ransacked the states to uncover among the people of the new nation exemplars of the arts and sciences whose accomplishments were sufficiently notable to warrant inclusion in the company of the centurys great men. In statesmanship Americans stood in the front rank; in science their record was creditable; but in the fine arts they could boast few names worthy of the notice of posterity.

Prior to the War for Independence two colonials had earned a place with the luminaries of the eighteenth centuryJohn Singleton Copley in painting and Peter Harrison of Newport in architecture. Yet neither in the Notes on Virginia (1782) nor in A Brief Retrospect of the Eighteenth Century (1803) can one find any mention of Peter Harrison, and one is led to ask why he has been so long forgotten.

There was dire need for artists in the Young Republic. A new and radical experiment in government was under way, and the eyes of the Western World were focused upon America. Could the arts flourish and attain perfection without aristocratic patronage, demanded the skeptics of monarchial Europe. The only answer was the development of a new art, and, especially, a new architecture expressive of republican virtue.

Despite the fact that every one of Peter Harrisons buildings survived the Revolutionand in fact is still standingpatriots dared not adduce as proof of their artistic maturity the work of a Tory tarred with the additional odium of service in the Kings Customs. Thomas Jefferson, moreover, never traveled to Rhode Island or Massachusetts, and went to his grave ignorant of the fact that Peter Harrison had anticipated him in the revival of classical models. He never knew that the loyalist was his precursor in the evolution of a new, pure form of architecture that would reflect the republicanism of the New World.

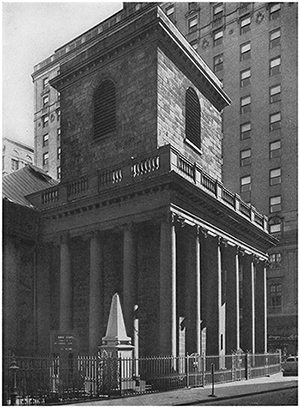

When the passions born of conflict subsided and historians turned to the study of the Tories, Peter Harrison remained in oblivion because a New Haven mob had totally destroyed his papers and drawings. Consequently, any study of the man and his work has to be made from stray materials found in the correspondence of other persons of his time. This biographical essayfor it cannot be termed a fulldress biographyis thus the fruit of accidental research undertaken over a long period of years. There are many gaps in this story of Peter Harrison and his buildings, but I believe that I have presented the broad outlines and most significant aspects of his career. Because so little is known about any of the colonial architects, it seems fitting to publish this account of the first great American designer on the two hundredth anniversary of the completion of his plan for Kings Chapel at Boston.

The illustrations are an integral and indispensable part of this book, and have been arranged to facilitate their use in connection with the text. Figures that are mentioned in the discussion of particular buildings and Peter Harrisons bookish sources are grouped together near the end of the volume, while those that bear more directly upon his life are inserted at appropriate places in the text. The captions are intended to amplify the text and assist the reader in relating the illustrations to the discussion of the buildings.

No author could have succeeded in his quest for materials about Peter Harrison without the generous and interested assistance of many friends and, perhaps even more, of persons to whom he was a complete stranger. I am privileged to be able to record my gratitude to all of them.

When I first seriously began to investigate the career of Peter Harrison, Miss Mary T. Quinn, efficient custodian of the Rhode Island State Archives at Providence, discovered documents that made further progress possible. Mrs. Peter Bolhouse, Leonard Panaggio, and Herbert Brigham of the Newport Historical Society industriously searched for items I could not find during my several visits to Newport. Mr. Maurice P. Van Buren of New York City placed his collection of Harrison materials at my disposal without restriction, thoughtfully presented the Institute with photostatic copies of the only remaining letters of his ancestor, and enabled me to have photographs of the portraits of the Harrisons.

Miss Mary S. Batchelder of Cambridge, with rare graciousness, gathered notes and other papers of her brother, the late Samuel Francis Batchelder, and gave me unrestricted access to them. Mr. Batchelders papers, the fruit of twenty-five years of research on Peter Harrison, proved invaluable to me.

The Reverend Henry Wilder Foote of Cambridge, who has identified Nathaniel Smibert as the painter of the Harrison portraits, kindly communicated this information to me when this book was in galley proof.

The following individuals and institutions assisted me in uncovering materials: Frank Malloy Anderson of Hanover; Miss Helen Boatfield and Mrs. Robert C. Bruch of New Haven; Mrs. Eleanor J. Brackett and Miss Frances Hubbert of the Redwood Library, Newport; Professor Dora Mae Clark of Wilson College; Antoinette Downing of Providence; Hunter Dupree of Cambridge; the late Allyn Bailey Forbes and Stephen T. Riley of the Massachusetts Historical Society; John H. Greene, Jr., of the Newport County Court; Brooke Hindle of Williamsburg; the Reverend Palfrey Perkins of Kings Chapel, Boston; Granville Prior of the Citadel, Charleston; Clifford K. Shipton of Shirley; St. George L. Sioussat of Chevy Chase; and Walter Muir White-hill of the Boston Athenaeum.

Also, the officials of the Avery Library at Columbia University; the Library of the College of William and Mary; the Connecticut State Library at Hartford; the Harvard University Library; the Historical Society of Pennsylvania; the Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery at San Marino; the Library of Congress; the Mariners Museum at Newport News; the New Hampshire Historical Society at Concord; the New York Public Library; the Rhode Island Historical Society at Providence; and the Yale University Library, placed every facility at my disposal.

Roberta H. Bridenbaugh, Douglass Adair, and Lester J. Cappon have read the manuscript in its several drafts and have suggested many improvements, both in organization and style. A. Edwin Kendrew, William S. Perry, and Fiske Kimball have generously aided me in architectural matters, while Mrs. William Phelan and Miss Margaret Kinard rendered great assistance with the manuscript.

My greatest debt is to A. Lawrence Kocher, who not only allowed me to use his unrivalled library of eighteenth-century architectural books, but patiently guided an importunate novice through the maze of architectural history and saved him from making many blunders. To him I have ventured to dedicate this book.