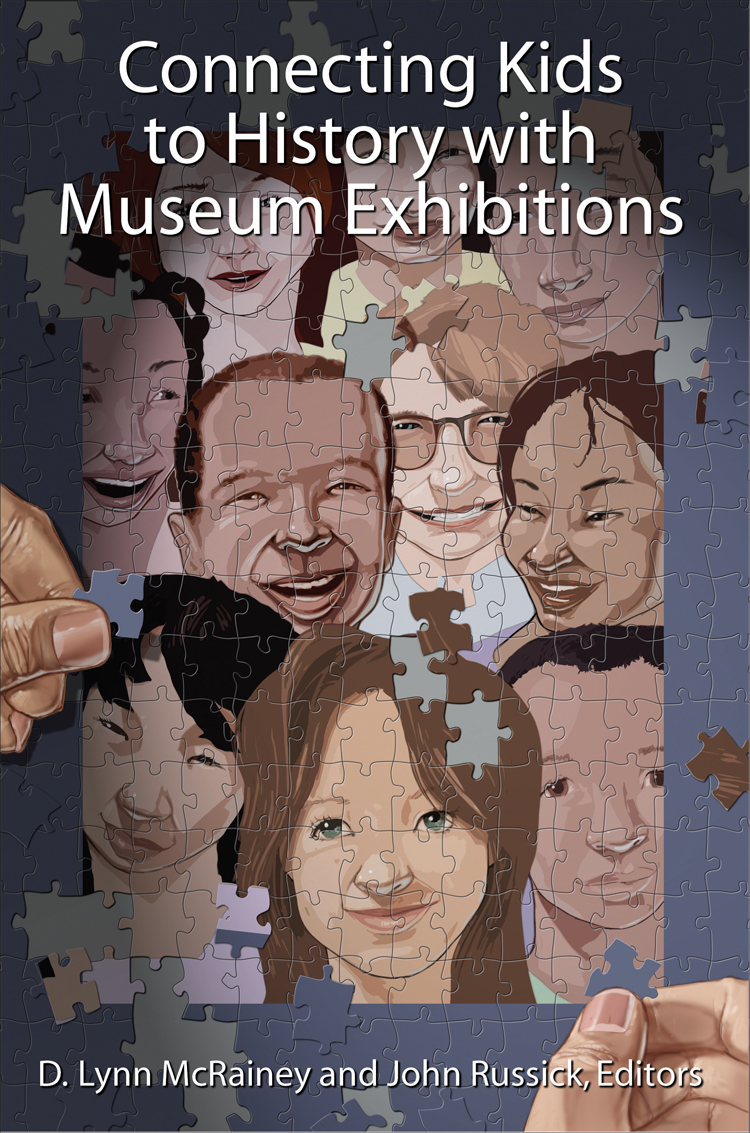

Connecting Kids to History with Museum Exhibitions

Connecting Kids to History with Museum Exhibitions

D. Lynn McRainey and John Russick

EDITORS

First published 2010 by Left Coast Press, Inc.

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2010 Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Connecting kids to history with museum exhibitions / D. Lynn

McRainey and John Russick, editors.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-59874-382-1 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-59874-383-8 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. MuseumsEducational aspectsUnited States. 2. MuseumsSocial aspectsUnited States. 3. Museum exhibitsUnited States. 4. HistoryStudy and teachingUnited States. I. McRainey, D. Lynn. II.

Russick, John.

AM7.C596 2009

069.15dc22

2009029019

Cover illustration and design by Michael Kress-Russick.

Part introductions photography credits are as follows: ) Childrens Discovery Museum, Normal, Illinois, photograph courtesy Ken Kashian.

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum gave permission for the use of , photos of Remember the Children: Daniels Story. Please note that the views or opinions expressed in this book, and the context in which the images are used, do not necessarily reflect the views or policy of, nor imply approval or endorsement by, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Paperback ISBN 978-1-59874-383-8

Hardback ISBN 978-1-59874-382-1

DEDICATION

To Alan, who never forgot what it was like to be a kid

To Miss Ann and Archie

CONTENTS

Among the variety of museums in the United States today, those interpreting history are the most numerous and, by virtue of their content rooted in the uniqueness of specific localities, also arguably the most diverse. Many museums devoted to preserving the past, or to capturing the ephemeral present as it quickly becomes history, take familiar form as historic sites, house museums, or free-standing state and local historical societies. Others are devoted to the histories of particular cultural groups or to exploring historical narratives associated with the development of industries, art forms, and businesses (motorcycles, music genres, transportation, flour milling, and computers are only a few recent examples). Still other history organizations preserve sites imprinted with meaning by virtue of their association with significant events or with memorable personalities. And as diverse communities have blossomed across the countrys social landscape, new museums have also taken root, nurturing historical memory with collections that document these communities origins, exhibitions that celebrate their achievements, and heritage programming that connects the generations.

Because they are so numerous and diverse,as underrepresented in their audience profiles, children and families can be one of the most important opportunities for history museums to broaden public engagement with the stories latent in their collections. But until quite recently, manyindeed, perhaps mosthistory museums have extended only minimal gestures to reach these audiences.

For example, for quite some time (at least as long as we have collected systematic data, and likely much longer), the Chicago History Museums most numerous visitor segment has been older adults, primarily empty nesters who visit alone, in pairs, or in organized groups. Until quite recently, this visitor profile was presumed satisfactory: efforts to engage families with children focused primarily on once-a-month weekend programming and on an aged Hands-on History Gallery whose isolated and outdated demonstration units lacked any kind of unified storyline or purpose. Children were seldom if ever seen as the primary audience for new exhibitions and the museum staff had little experience with the interpretive and design tools needed to engage them. Our narrow audience focus shaped our exhibition processes and products in ways that are evident only in retrospect. We knew our collection and how to explain any one of its objects with no more than seventy-five words on an attractively designed label panel. We had honed our editing skills to encapsulate whole chunks of history into three-minute videos and posing Q&A issues on flip-up labels. Once in a while our budgets allowed us to develop an interactive computer program. We figured we knew which stories mattered, and since the way we told them was so interesting to us, we didnt pay much attention to who else was listening. Almost (but not quite) unconsciously, we had chosen to make exhibitions for ourselves, relying on teachers, chaperons, parents, and docents to do the heavy lifting for kids. This practice ignored the fact that about a third of our museums total attendance was comprised of student groups, the majority from elementary school classrooms.

Although, like the Chicago History Museum, most history museums attention to children may still be in its infancy, over the past twenty or more years some of these museums have instead been very engaged in audience development focused on issues of diversity, representation, and interpretive voice. While many museums (including most state and local historical societies as well as house museums) continue to enjoy enduring relationships with the traditional constituencies that have built their collections over generations, they also recognize that the demographics of their surrounding communities have changed. Many of their new neighbors feel an uncertain connectionor no connection at allwith the past that traditionally has been represented in history museum exhibitions and programs. Recently arrived in a new location, families are focused on making that place a foundation for their future, and a history that does not include them seems peripheral to their concerns. In common with previous generations of Americans, these audiences look to the future and seek pathways to it. We envision a future lying before us. History lies behind, and we often struggle to see any value in looking back.

As history museums become experienced in audience research and more nuanced in its interpretation and application, data demonstrates that these museums cannot build effective and long-lasting bridges with diverse communities until they are attractive to these communities families and their children. Research shows that visitors most enduring connections with museums are based on their experiences as children during family visits. Reflecting on findings from a survey of museum attendance studies, John Falk posits, Proactive efforts to involve more families in museum experiences will lead to increased attendance and support in the future. These families must have reasons to visit us, they must feel welcomed, and their experiences must be rewarding. To gain their attention, we must compete with myriad other scheduled commitments and attractive entertainment options. History museums need to recognize and embrace their opportunity to attract these families by offering unique leisure experiences that are not only entertaining but also meaningful for children.