Introduction

MIKE SABRON DIED ON JANU-ary 19, 2003, at St. Lukes Miners Memorial Hospital in Coaldale, Pennsylvania, just a few miles from his home in Summit Hill. We had the good fortune to interview Mike, a former anthracite coal miner, during the course of our study on the roots and consequences of sustained economic decline, a process all too familiar to regions and cities across the United States at the turn of the twenty-first century. Mike lived and worked in the Pennsylvania anthracite region, an area that first prospered on the mining of coal and then collapsed economically beginning in the 1920s with changes in the fuel marketplace. This regions history provides an opportunity to explore the causes of economic disintegration and the responses of capital, labor, communities, and government. Mike experienced the full brunt of the closing of the mines and the ensuing regional crisis, and his story speaks to the personal dimensions of economic decline.

Mike was part of a dying breed of men, literallya member of the last generation of Pennsylvania anthracite mineworkers. Mike began working in 1931 at the age of eighteen for Lehigh Navigation Coal (LNC), a company operating in the Panther Valley, in the southern portion of the region. He progressed through a series of jobs at LNCfirst in the bagging plant, then driving mules, loading coal, and finally, working as a contract miner beginning in 1947. As demand for anthracite coal declined after 1950, the mines worked only two or three days a week, and Mike and some buddies took painting jobs to supplement their shrinking earnings. In April 1954, however, LNC closed all its mines in the Panther Valley. Unemployed, and with a family to support, Mike joined a group of displaced miners and began commuting on a weekly basis to Linden, New Jersey, to work in a General Motors plant. He hated the regimen of the auto assembly line and jumped at the first opportunity to return to mining when one of the valleys collieries reopened in October. Mike worked almost continuously until the last underground mine in the area closed for good in 1972. After a short period of working at temporary jobs, Mike retired, soon getting involved in local efforts to preserve the history of anthracite mining. Mike Sabrons storyand scores of others we gathered from his fellow former miners, their wives, and childrentell of crisis, coping, resilience, and love of place.

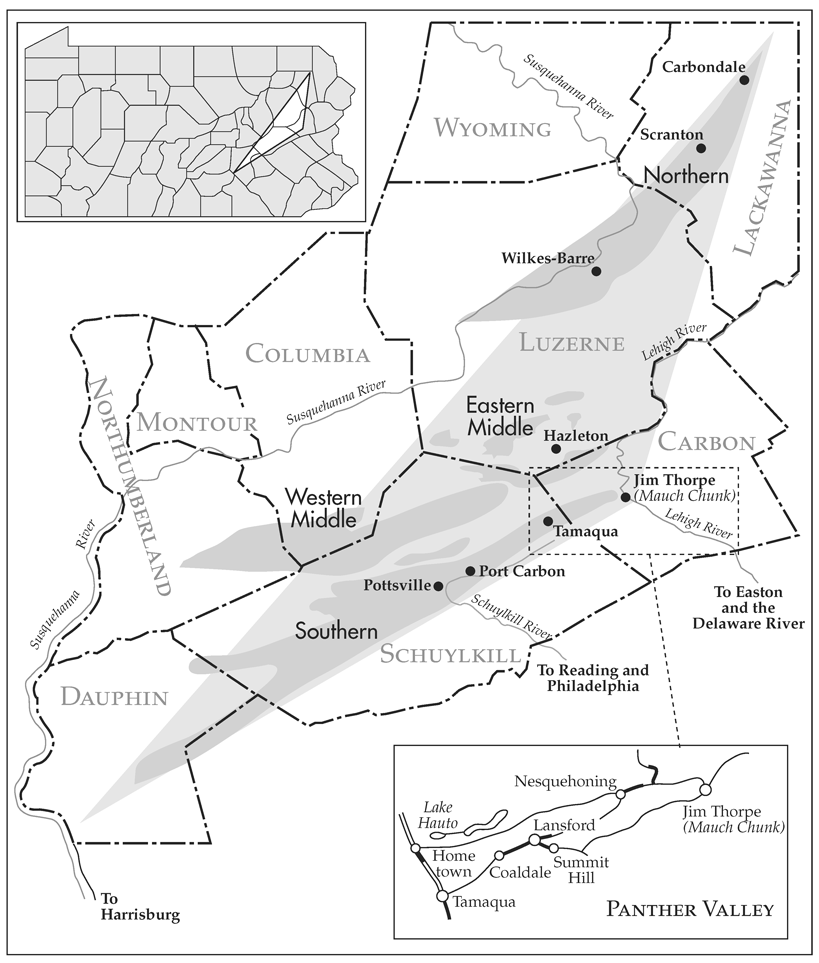

The place of Mike Sabrons life, the Pennsylvania anthracite coal region, contributed mightily to the rise of the United States to world economic supremacy. The region occupies a triangular area in northeastern Pennsylvania that begins near the Susquehanna River in Dauphin County north of Harrisburg at its southwestern point, extends in a north-northeasterly direction through Wilkes-Barre and Scranton in the Wyoming and Lackawanna Valleys to just north of Carbondale, then southward again to Jim Thorpe (formerly Mauch Chunk) along the Lehigh River, and, finally, back in a southwesterly direction through Carbon and Schuylkill Counties. Under the surface of this near-five hundredsquare-mile area lay 95 percent of the nations supply of anthracite coal, a fuel that powered U.S. industrialization, a remarkably efficient source of heat to generate steam, smelt iron ore, and warm the homes of the growing urban population of a modernizing nation. In 1890, this tiny area provided more than 16 percent of the nations energy consumption.

Coal played a singular role in the industrial transformation of Western Europe and the United States in the nineteenth century. Two forms of coalbituminous and anthracitebecame the major sources of energy that displaced waterpower and fueled the steam engines and locomotives that changed the character and pace of modern life. Bituminous, or soft coal, is far more common than anthracite, more amenable to mechanization, and continues to play a substantial role in the U.S. economy today as a fuel for generating electricity. Bituminous coal is found across a wide swath of Appalachia stretching from northern Alabama to western Pennsylvania, through Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois, and in Wyoming, Colorado, and Utah, while commercial anthracite deposits are limited almost exclusively to the tiny, triangular region in northeastern Pennsylvania.

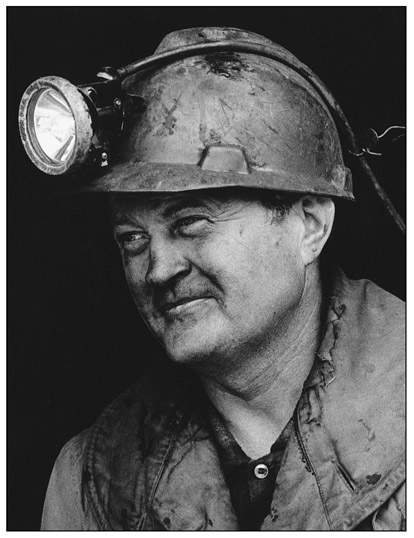

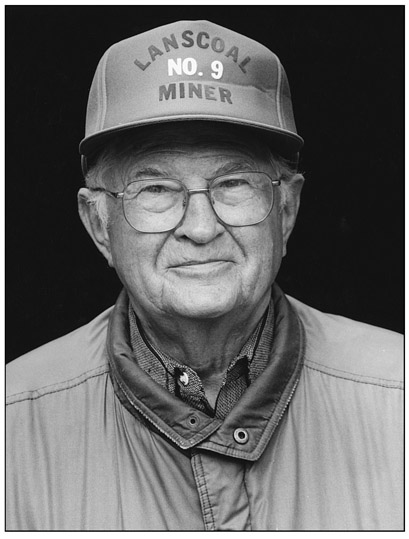

Mike Sabron while working at Lanscoal, ca. 1970. Photograph by George Harvan.

The emergence of anthracite mining in the nineteenth century wrought dramatic economic, environmental, and social changes in northeastern Pennsylvania. With the discovery and extraction of coal, the area bustled with entrepreneurial activity, rapid canal and railroad building, and corporate growth and the deepening involvement of finance capital. The population exploded as successive waves of European immigrants arrived. At the centurys beginning, only three or four residents per square mile lived in the sparsely settled, undeveloped region. By 1900 population density averaged 293 people per square mile and area mines were producing fully 57 million tons of anthracite coal annually. What had been an utter wilderness became the anthracite coal region.

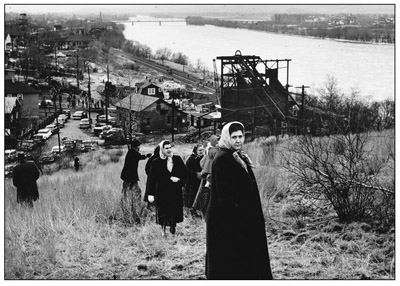

Mike Sabron, Lanscoal miner, Lansford, fall 1996. Photograph by George Harvan.

The expansion of mining required vast labor power. Immigrants came first from England, Wales, Scotland, Ireland, and Germany, and then from southern, central, and eastern Europeall of whom made the region rich in ethnic institutions and folklore. These newcomers soon encountered perilous and exploitative working conditions and participated in repeated and legendary labor battles, conflict that remained characteristic of the anthracite region into the middle of the twentieth century.

The history of the anthracite region in the period of its ascendancy is alluring and has attracted generations of chroniclers and scholars. World War I, however, marked the industrys peak. Starting in the 1920s, anthracite coal lost its market to much less expensive and more convenient fossil fuels, particularly oil and gas, but also bituminous coal, and the region entered an enduring economic decline. The areas contribution to and presence in the national experience began to fade. This book explores the Pennsylvania anthracite region during these difficult times. Extensive sections of U.S. cities and counties that once brimmed with industry now lay fallow. For Americans of the twenty-first century, the long-term economic collapse and stagnation of areas are an unavoidable chapter in the history of the nation. The Pennsylvania anthracite region, an early example, illuminates the dynamics of decline: the roles of capital, labor, and the state and the impact on and responses of communities, families, and individuals.