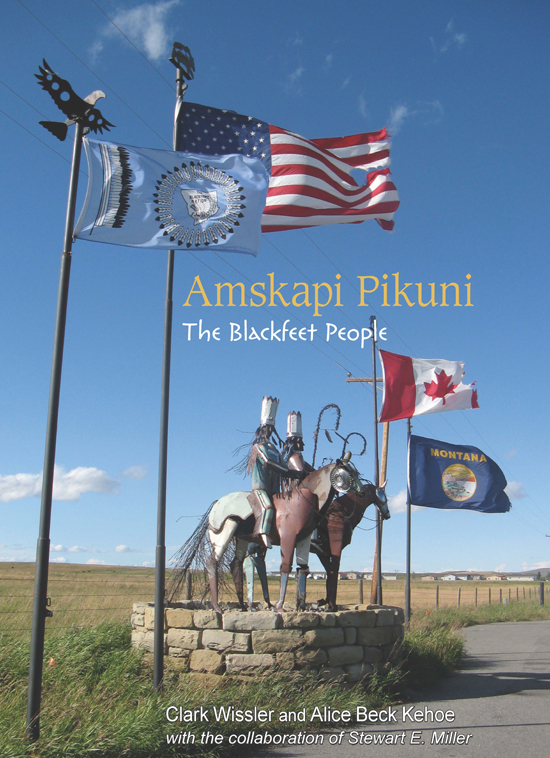

FRONT COVER PHOTO: Scouts, sculpture by Jay Labre, at northern highway entrance to Blackfeet Reservation. Credit: Alice Kehoe.

BACK COVER PHOTO: Tribal bison herd on Blackfeet Reservation. Credit: Alice Kehoe.

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2012 Clark Wissler and Alice Beck Kehoe

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Production by Ryan Morris

Marketing by Kate McDonnell

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wissler, Clark, 1870-1947.

Amskapi Pikuni : the Blackfeet people / Clark Wissler and Alice Beck Kehoe; with the collaboration of Stewart E. Miller.

p. cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4384-4335-5 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Siksika IndiansHistory. 2. Siksika IndiansGovernment relations. 3. Siksika IndiansCultural assimilation. I. Kehoe, Alice Beck, 1934 II. Miller, Stewart E., 19502008. III. Title.

E99.S54W488 2012

978.004'97352dc23

2011048815

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Preface

Amskapi Pikuni, like other American First Nations, have emerged from the shadow of imperial domination that darkened their land when the bison herds disappeared. Now that bison once more live among us, the people of this nation want to retell their history as it was experienced.

Just a century ago, a young man who had grown up in Indiana farm country came out to Browning to purchase Blackfoot manufactures for exhibit and study in New Yorks American Museum of Natural History. Clark Wissler hired as his interpreter David Duvall, son of Yellow Bird (Louise Big Plume) and her French Canadian husband from Fort Benton trading post. Duvall's father died when he was a young boy, so Yellow Bird returned to her reservation and settled in Heart Butte, where she married Jappy Takes Gun On Top. David was sent to Fort Hall Indian School, in Idaho, where he learned to speak and write English as well as the trade of blacksmithing. Wissler's project of preserving Piegan elders' knowledge by means of writing excited Duvall, and Wissler, in turn, was impressed by Duvall's talent for interviewing and his intellectual ability. Soon Duvall became a full collaborator in the project, working throughout the year while Wissler was in New York. Tom Kyaiyo (Sanderville) and other men of Heart Butte seem to have willingly dictated to Yellow Bird's son: we must remember that then, 190511, the first generation to have grown up on the reservation had come to adulthood, everyone had settled into the new way of life, and more and more children were taken from their families to be drilled into Anglo speech and habits. No one was coercing the men to cooperate with Dave Duvall; his employer, Wissler, took pains to avoid antagonizing the agency superintendent but was much more comfortable with Indian people. Wissler and Duvall openly respected the people, in an age when it was conventional to call them degraded savages.

Wissler gave up coming to the reservation in 1909, weakened by a chronic condition that persisted until 1928. Memories of the beauty of the mountains and High Plains, and the impressive people native to the land, remained strong. As he applied himself to supervising the American Museum's wide range of research with First Nations, Wissler never stopped thinking about how Blackfoot had survived and prospered for thousands of years in country so different from the farmlands Europeans knew. His framework for analyzing Blackfoot success would be human ecology, a term Wissler seems to have been the first anthropologist to use in our contemporary sense. Twenty years after completing writing up the material collected by Duvall (who committed suicide in 1911), Clark Wissler began a history of the Blackfoot Indians in contact with white culture. In simple words, it would be a history of Piegan standards of living, how they interacted with their natural world and, when that was disastrously disrupted in the 1870s, how they coped with Anglo invasion. The book was well sketched out in 1933, then left unfinished as Wissler addressed more immediate obligations.

In 2003, I stopped in Muncie, Indiana, to look at an archive of Wissler's papers held in the anthropology department of Ball State University. Most of the boxes held routine correspondence from his years at the American Museum. One box contained a surprise: his unsuspected manuscript on Blackfoot history. The more I read of the manuscript, discussed the human ecology approach with colleagues, and talked with Piegan friends, the more I was convinced it would be worthwhile to complete what Wissler had shelved.

What follows is Wissler's manuscript, filled in with references he notated but left uncopied, presented as , to Clark Wissler's life and work.

The book took its shape from discussions with several Piegan colleagues, particularly Stewart Miller, Linda Matt Juneau, Carol Tatsey Murray and John Murray, Darrell Robes Kipp, Dorothy Still Smoking, Shirlee Crow Shoe, Rosalind La Pier, Kathy New Breast McDaniel, Fred and Ramona DesRosier, Lea Whitford, Marvin Weatherwax, Wilbert Fish Sr., and Stan Juneau. I am deeply grateful to them and to those many others at the Blackfeet Community College, Browning Public Schools, Nizipuhwahsin School, and elsewhere on the reservation who have extended such warm hospitality and friendship. My gratitude goes also to Alberta Blackfoot scholars, especially Narcisse Blood, and my Calgary colleagues, particularly Sarah Carter, Donald B. Smith, Brian and Susan Kooyman, Gerald and Joy Oetelaar, Gerald Conaty, Barbara Belyea, and Mary Eggermont-Molenaar. Piegans Darrell Norman, David Dragonfly, and Jim Kennedy contributed from their specialties. I acknowledge Earl Old Person, now and forever Chief of the Blackfeet Tribe, the late Bob Scriver who knew more about most people than they wanted, and his surviving partner Mary Scriver. I thank Mike Wikstrom for special friendship, and in Milwaukee, archivist par excellence Mark Thiel. Eric and Beth Lassiter got me to Muncie, and made visiting it a treat. Let me close with memorializing Mollie and George Kicking Woman, Mae Williamson, Katie Croff, and Stewart Miller. They shine brightly now in the night sky.