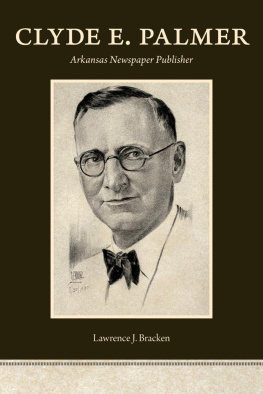

CLYDE E. PALMER

FOREWORD

By Walter Hussman Jr.

I WAS ONLY TEN YEARS old when my grandfather died, so I later learned more about him only from the stories and there are many, as you will read in the pages that follow. His name was Clyde Eber Palmer, and he began a commitment to local journalism in the public interest that now spans four generations of our family.

I was two years old when my parents bought the Camden News in Arkansas from my grandfather and moved my two older sisters and me from Texarkana to Camden. My sister Marilyn was eight, and Gale was eleven. They had grown up in Texarkana where my grandparents also lived. My father was away in World War II for several of those years, so they spent meaningful time with our grandparents and knew them much better than I.

Marilyn recounts fond memories of our grandfather. For about six weeks when our parents were in New York awaiting word for dad to ship off to World War II, both of my sisters lived with my grandparents. Marilyn remembers playing checkers and other games with our grandfather in the upstairs study, and she attributes her love for games to those experiences with him. She also remembers him teaching her how to water ski on Lake Hamilton outside Hot Springs. She remembers being pulled around the lake on a water board and that he, in his seventies, also rode the water board.

Gale shares lasting memories of times at the lake with grandfather, when he taught her to swim and ski. And she remembers him sitting at the breakfast table with her drawing Europe and North Africa on a tablecloth to explain the battles being fought in World War II. Gale will tell you that our grandparents were the most important people in her formative life, teaching her the love of books and ideas. She remained close to them the rest of their lives.

There are so many stories that have been passed down to me about C. E. Palmer. Here are a few of my favorites.

After I started working for the company in 1970, the advertising director in Texarkana also an aviation instructor told me he had taught the seventy-five-year-old Palmer how to fly. He specifically remembered the day of Palmers first solo flight. He told Palmer to simply take off, make two left turns, get into the downwind leg, turn on the base leg, and then turn 90 degrees and come down for a landing. As a pilot, I know this is the standard for a first solo flight. The instructor watched Palmer take off, make one left turn and then just disappear over the horizon. The instructor went into a cold sweat. Palmer might crash. He might be hurt or killed. He himself would lose his job. And worst of all, my grandmother, Palmers wife Bettie, would learn he was secretly teaching her husband to fly. He waited nervously. A half hour later, he saw a plane headed west coming his way. It approached the Texarkana airport and landed. It was C. E. Palmer. Relieved, he asked Palmer where he had gone. Palmer replied he simply followed the highway and flew up to Hope, Arkansas, and back. Palmer always followed his instincts and rarely fit a mold.

My favorite story is about when Palmer met William Dillard. Dillard was from Nashville, Arkansas, and opened his first store there when he was twenty-four years old. After eight years, he was ready to expand, and he came to Texarkana. One of his first meetings there was with the local publisher, C. E. Palmer. It was 1946; Dillard was now thirty-two years old, and Palmer was seventy. He told Palmer he wanted to open the towns first department store, but he didnt have enough capital to do it. He said if Palmer bought stock in his company, he would become Palmers largest advertiser and that Palmers retail advertising would increase 50 percent. Palmer had never done anything like that, but he later agreed. After he had invested and the store was up and running, Palmer called Dillard one Christmas Eve and asked him to lunch. At lunch, Palmer said that Dillard had not been honest with him. This puzzled Dillard, a man of high integrity. Palmer then told Dillard he had indeed become his biggest advertiser, but his business had doubled, not increased by merely 50 percent. Palmer said that if he never got a nickel out of the stock, it would be the best investment he ever made.

I first heard this story from my father, then I heard Dillard tell it himself. It was January 9, 1990, at the annual convention of newspaper advertising executives in Palm Springs, California. I flew out on American Airlines early that morning so I could hear Dillards keynote speech at noon. (Listen to the speech at arkansasonline.com/wdillard01091990.)

After lunch, major advertisers like Sears, JCPenney, Kmart, Macys, and of course Dillards, participated in roundtables where newspaper ad executives could come talk with them. I went to the table with William Dillard and stayed as ad executives from newspaper companies like Tribune, Knight Ridder, McClatchy, and Gannett came by to visit. As the discussion concluded, Dillard looked over to me and asked when I was going home. I told him I had a flight later that afternoon on American Airlines. He invited me to instead fly home with him on his plane. I noticed with some satisfaction that the representative from Gannett, with whom we were in fierce competition in Little Rock, overheard the invitation. On the flight back to Arkansas, I learned a lot about Dillard and his business philosophy. It was quite a day.

Another story featured Ross Perot. Perot grew up in Texarkana and was a paperboy at age fourteen for Palmers Texarkana Gazette , delivering the paper on horseback. He was given a route in a poor part of town where the collections were often difficult, so the carrier got a low wholesale rate to compensate. Perot not only solved the collection problems, but he expanded subscribers and managed to have a very profitable route, given the low rate. The circulation director noticed and raised his rate. Perot objected. He was told his only appeal would be to the owner. So he went to see Palmer, and Palmer sided with him. When Perot ran for president, he addressed newspaper publishers at their annual meeting at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York. Like William Dillard, he told his C. E. Palmer story, and I was fortunate enough to be in the audience to hear it.

In reading this book by Larry Bracken, I have reflected on how my career has differed from my grandfathers. While I worked on consolidating ownership within our family, he often sought outside investors. While I followed my fathers strategy to buy and hold properties to realize a return by operating them, Palmer would often buy a newspaper and sell it within a few years. My grandfathers passion was business mostly in newspapers and then broadcasting but he would invest in anything he considered profitable, including real estate, oil, and gas. Palmer once started a newspaper in Fort Smith, and when it proved difficult and unprofitable, he pulled out after a year. In contrast, we bought the struggling Arkansas Democrat in 1974 and despite enormous challenges competing with the larger Arkansas Gazette (first owned locally for more than a decade of our competition and then owned by the countrys largest newspaper company, Gannett, for the next five years), we persisted, and we prevailed.