Editors:

Kenson Kwok

Heidi Tan

Photography:

Kuet Ee Foo

Lee Chee Kheong

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Copyright National Heritage Board 2002

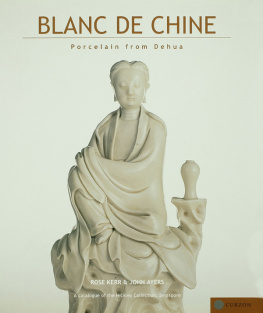

Introductory Remarks on Dehua Ware Rose Kerr 2002

Blanc de Chine: Some Reflections John Ayers 2002

Blanc de Chine in Archaeological Perspective: A Tribute to Donnelly Chuimei Ho 2002

Dehua Porcelain in the collection of Augustus the Strong in Dresden Eva Strber 2002

Published in 2002 by

Curzon Press

Richmond, Surrey

http://www.curzonpress.co.uk

ISBN: 0 7007 1713 7

Colour separations by Colourscan Pte Ltd

This book is dedicated to Pamela Hickley and the memory of the late Frank Hickley, on the occasion of the gift of their Dehua blanc de Chine porcelain collection to the Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore, 2000.

Introductory Remarks on Dehua Ware

Rose Kerr

W e have known for many years that porcelain of the qingbai type was made from the Northern Song dynasty onwards, at kilns in the Dehua and surrounding areas of central Fujian province.1 Recent excavation has clarified the location and sequence of kilns making qingbai porcelain, and has unearthed a significant whiteware that acted as an intermediary between qingbai and later blanc de Chine. Chuimei Ho celebrates work by Chinese archaeologists and interprets their finds for a wider, western language audience. The discussion of the ceramic for which the Dehua kilns came to be most famous, whose quality Pamela Hickley understandably admires, is the major subject of all the authors in this book. This ceramic was not made till the mid-Ming dynasty, when refinement of body and glaze led to the manufacture of lustrous white wares, later known in Europe as blanc de Chine and in China as pork-grease white (zhuyoubai) or ivory white (xiangyabai). John Ayers reflects on some of the earliest fifteenth to sixteenth century wares that could be considered true blanc de Chine.

The peak of production of blanc de Chine has been judged to be the seventeenth century. A technological treatise by Song Yingxing, Tiangong Kaiwu (The Exploitation of the Works of Nature. 1637: 5b) noted that fine clay came from Yongding district, about 175 kilometres southwest of Dehua. Materials were mined from local deposits, Dehua wares being made from porcelain stone alone or with very small additions of clay. The porcelain stone was crushed with water-wheels () in the same manner as Jingdezhen, then purified and levigated in tanks of water. Formation of wares could be complex, particularly figurines, and Kenson Kwok clarifies construction methods. Wares were fired in stepped, chambered kilns built up on hillsides. Firings of the high-temperature kilns were expensive, and a twentieth century text informs us that they were generally shared between several families. It is likely that the same practice obtained in earlier times. Wealthier clans would fill two or three separate chambers with pieces, while poorer potters would only have the use of a single chamber (Wang 1936: 7). Dehua workshops turned out a variety of vessels, many for use in temples and tombs. The best-known merchandise was porcelain figures, mainly of Buddhist deities. Many of the finest pieces were subsequently exported, and evidence from examples that found their way abroad is discussed by John Ayers, Chuimei Ho and Eva Strber. Strber expounds on one of the most famous collections of all, that of Augustus the Strong.

Figure 1: Guanyin with baby seated on a lion. Height: 14 cm, 17th18th century, (cat. ref. 9).

Figure 2: Water-wheel used to crush porcelain stone. Dehua 1993. Photograph: K. Kwok

Dehua was one of the few production centres where potters signed their names. Another such was Yixing, whose red stonewares were sought after by connoisseurs for whom signed products gave enhanced value. Dehua was a different case. Teapots, cups, vases and figurines were made for a largely local market within China, and used in the home, local temples, domestic shrines or tombs. They were not sought after by connoisseurs, nor written about in glowing terms in the Ming dynasty. Indeed, the author of Tiangong Kaiwu opined that Dehua specialised in making porcelain Buddhas and delicate figurines of no great practical value (Tiangong Kaiwu. Chapt.7:5b). The broader tastes of the Qing dynasty allowed one scholar to give grudging praise, commenting that most Dehua was very thick-bodied but some of the Buddha figurines were especially refined (Jingdezhen Taolu. Chapt. 7: 6b).

As this volume makes clear, Dehua porcelain was exported, and many export pieces were signed by their makers. Certain family names were prominent in the industry: He, Chen, Yan, and Su were especially common. In 1936, an industry handbook noted eight villages in the Dehua area engaged in workshop manufacture, with different clans active in each locality (Wang 1936: 2)

Village | Clans Names | No. of Kilns |

Baomeixiang | Mainly Su | |

Dongtoucun | Zheng | |

Gaoyangcun | Chen | |

Nanlingcun | Yan | |

Huangcicun | He | |

Letaocun | Sun, Chen | |

Housuocun | Chen, Lin | |

Dinggancun | Chen | |

Among the earliest potters to be associated with the region wasYan Huacai (864933), who worked as a potter under the tutelage of an uncle who was foreman of a factory at Si Bin, an area where large kiln waster heaps record former activity. Most Dehua potters names, however, are associated with the period of greatest skill and achievement in the second half of the Ming dynasty. Dehuas most renowned potter was He Chaozong, whose works are represented in collections around the world. Hes family is said to have moved to Fujian from Jiangxi province in the Hongwu period (136898), his ancestor being employed in militia deployed to combat coastal raids. The family settled at Longtai village in 1384, a hamlet at the centre of the later Ming dynasty pottery industry (Xu 1993:18). He was first mentioned in the 1612 edition of Quanzhou Fuzhi, and although little is known about his career, some Chinese scholars believe him to have been active sometime between 1522 and 1612 (Zeng 19956: 26. See also Donnelly 1969: 270276, 309). He started by making clay images for temples, and later graduated to white porcelain. A disciple and relative of He Chaozong, He Chaochun, followed in his masters footsteps in creating votive images. Many were exported to Europe in the seventeenth century (Xu 1993: 18. See also Donnelly 1969: 2767).