Curry renders the stomach active in Digestion the Blood naturally free in circulation, the mind vigorous, and contributes most of any food to the increase of the human race.

(London) Morning Herald , 1784

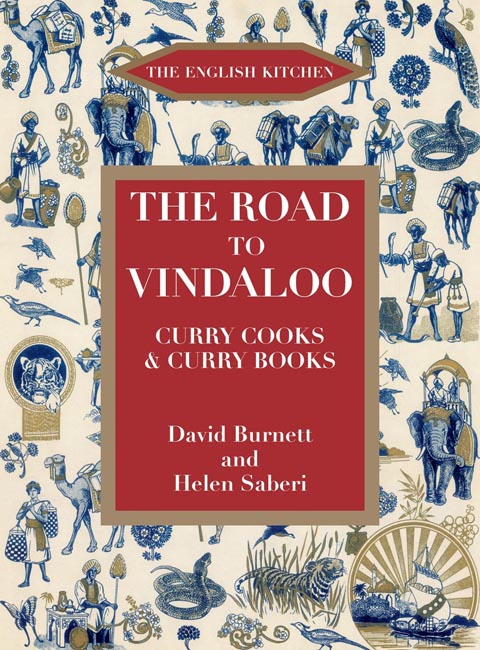

First published in 2008 by Prospect Books,

Allaleigh House, Blackawton, Totnes, Devon TQ9 7DL.

2008, David Burnett and Helen Saberi.

The authors assert their right to be identified as the authors in

accordance with the Copyright, Designs & Patents Act 1988.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data:

A catalogue entry for this book is available from the British Library.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright holder.

ISBN 978-1-903018-57-6

ePub ISBN: 978-1-909248-12-0

PRC ISBN: 978-1-909248-13-7

Typeset by Tom Jaine.

Printed and bound in Great Britain at the Cromwell Press,

Trowbridge, Wiltshire.

CONTENTS

PREFACE,

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND A

SORT OF INTRODUCTION

The British came here and stayed for 200 years. What

was their most significant legacy?

Railways? The Civil Service? Democracy? Surely it

was Cricket!

And what of most importance did they take from us?

Yoga? Mascara? Ashrams?

Surely it was Curry!

Danesh Carvallo

More than a dozen years have passed since I read the manuscript of David Burtons culinary history, The Raj at Table . The author had submitted it to the then independent publishing firm Victor Gollancz, where I worked. I liked the script very much and made Mr Burton an offer to publish which he rejected in favour of a better one from Faber, who published the book with some success. The chagrin from this disappointment eventually passed, as far as I was concerned, but the interest kindled by Mr Burtons book stayed with me.

Part of this interest came from my own experience of India. I had stayed in old resthouses of the Raj years and found sad relics in the gravestones of young men far from home and the decaying mansions of British administrators, abandoned and daubed with crude graffiti. (In a leafy residential part of Bangalore an old white wall round a crumbling colonial house bore the words, painted in thick black letters, NOT TO URINAT HERE. In the former British officers club in the same city, a notice glued above a leather armchair in the library smoking room announced, SMALL EATS ONLY. On the bookshelves, hundreds of dilapidated novels by authors like Dornford Yates were inexorably turning to powder.) To a person of my generation, born before World War II and taught at schools where maps of the world on classroom walls showed large land-masses coloured imperial pink (ours), such glimpses of a lost regime in India were both uncomfortable and fascinating. I found particular interest in the publishing and bookselling companies of the Raj years, firms such as Thacker & Spink, and Higginbotham, in Bombay and Madras, who published guides of all kinds for British readers. It was to these firms that the authors of local cookery books brought their works.

Enthused by Mr Burton and my experiences on the sub-continent, I started to look for old cookbooks on the shelves of bookish friends and in the catalogues of specialist booksellers. I started to buy them, too, which was very expensive. I took a readers ticket to the British Library, where the India Office collection is now held. There, I followed up on some of the authors, previously unknown to me, from whose pages David Burton had quoted: Colonel Kenney-Herbert, Henrietta Hervey, Flora Annie Steel, and others. In the library of the Wellcome Institute I discovered Mrs Turnbull and Captain White, pioneer entrepreneur of the curry paste. In Edinburghs City Library I perused the 200 year-old manuscript of Stephana Malcolm. I knew about Eliza Acton, having in my early days reprinted her great book Modern Cookery of 1845. I reread her curry chapter, once more marvelling at her thoroughness and the clarity of her instructions. I went to India again and searched the library of a good friend, M.Y. Ghorpade, in the palace of Sandur. Here I found Colonel Hare and Mrs Dey and the 1950s cookbook of the American School at Kodaikanal with its careful instructions for cake-making at high altitude.

The finest private library of which I took advantage belonged to Judy Weston, whose generosity was matched by her expert knowledge of the literature of the Raj. At first I searched out of curiosity and a natural tendency to wander down blind alleys; I had no idea of attempting to make a book, indeed I was sufficiently aware of my inability to tackle a serious project not to proceed in more than a dilettante sort of way, buying the odd book here, boring the odd friend there, cooking the occasional istoric curry dish. Yet gradually a folder began to ?ll with bits and pieces. Something was taking shape, or it should have been, if I had been able to impose a structure upon it. I could not. I was floundering, bogged down in details, unable to see the wood for the trees, and so on. Then I met Helen.

After the publication of her book Afghan Food and Cooking in 1986, Helen worked for 15 years with Alan Davidson, including assisting him in the immense task of compiling the Oxford Companion to Food . Together, they also produced a small classic on the history of trifle. After Alans death I was lucky enough to inveigle Helen into the stalled and struggling curry project and she has helped me turn it into a finished article. Without her, the book would never have seen the light.

I am particularly grateful to Tessa McKirdy of Cooks Books, who provided some crucial works from her store, and much expert knowledge. In Edinburgh, Olive Geddes guided me through the papers of Stephana Malcolm. We are also indebted to Bee Wilson for kindly reading through the manuscript and making many helpful suggestions. Warm thanks also go to Hilary Hyman who helped us in many ways: scouring the charity shops for little-known books and valiantly testing a number of recipes. Other friends and family have also helped us both with suggestions and tasting recipes and we thank Nasir Saberi, Alex Saberi, Oliver Saberi, Colleen Taylor Sen, Philip and Mary Hyman, Jane Davidson and Jean Miller. We also express our gratitude to all the other authors who have given permission for us to use information or recipes: Jennifer Brennan, Pat Chapman, Sir Gulam Noon, Camellia Panjabi, Marguerite Patten and Charles Perry.

Finally thanks and gratitude go to our publisher Tom Jaine for publishing this book and producing such a handsome edition.

David Burnett

ABOUT THIS BOOK AND THE RECIPES

What this little book aims to do is trace the history of the British curry by way of cooks and books from medieval times to colonial India and to Britain from the eighteenth to the twenty-first centuries. We aim to show the evolution of curry from a medieval spiced stew to its modern interpretation.

Many of the recipes have been tested but at the same time most of the old ones, given verbatim, come from the original source. We felt that readers would prefer to see for themselves what, say, an author of the eighteenth, nineteenth or twentieth century wrote without the substitutions which would be the almost inevitable results of testing. Given the huge number of curry recipes in cookery books over the last 250 years or so, making a selection became a matter of personal taste. We have given a broad choice: those of interest, of importance historically, and those we thought were just too good to miss.

Next page