Contents

Guide

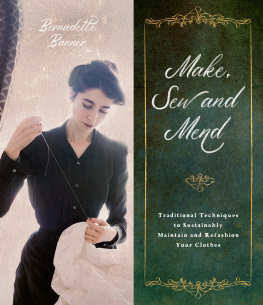

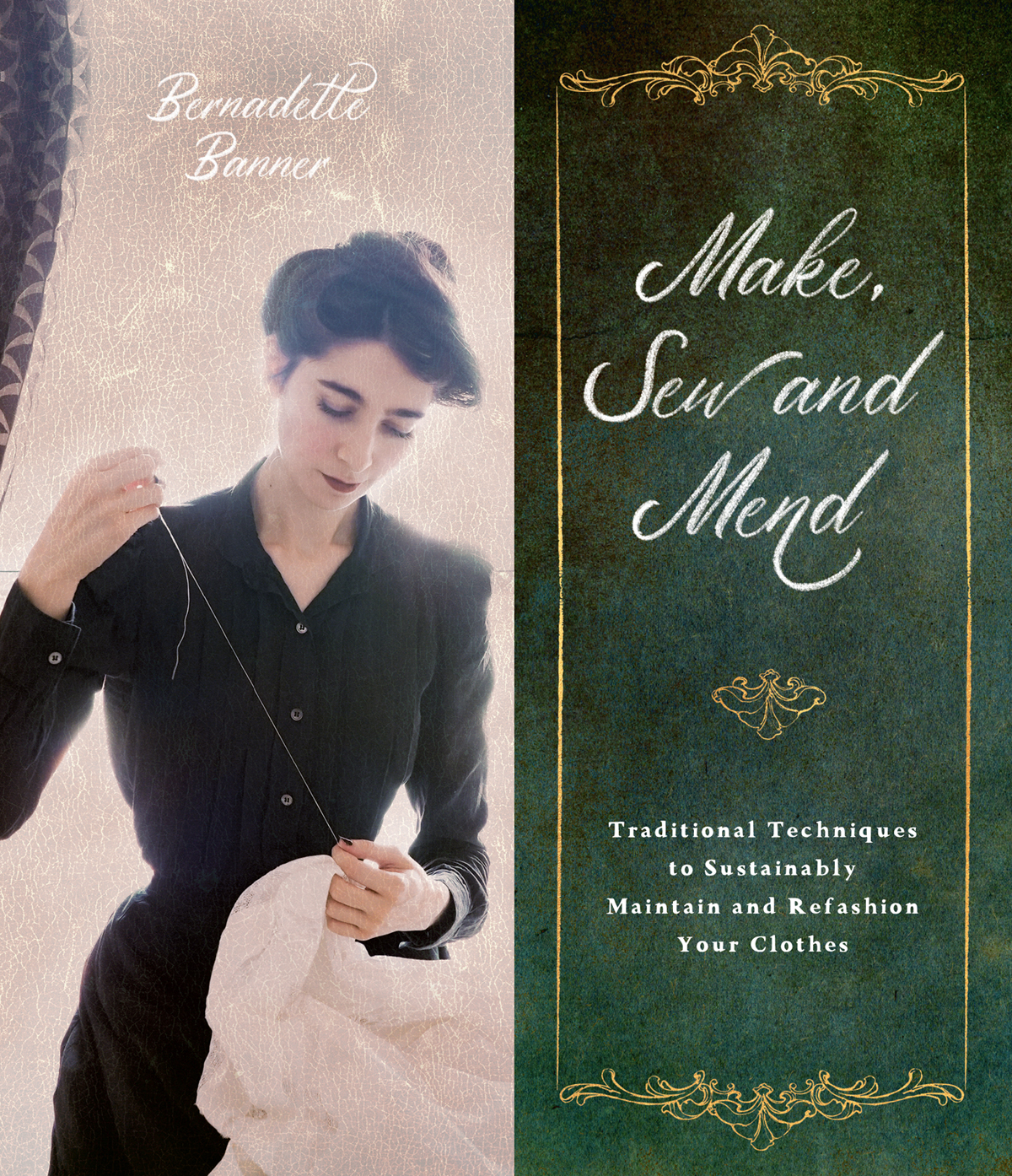

Make, Sew and Mend

Traditional Techniques to Sustainably Maintain and Refashion Your Clothes

Bernadette Banner

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: http://us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Copyright 2022 Bernadette Banner

First published in 2022 by

Page Street Publishing Co.

27 Congress Street, Suite 1511

Salem, MA 01970

www.pagestreetpublishing.com

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or used, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Distributed by Macmillan, sales in Canada by The Canadian Manda Group.

eISBN 978-1-645674-87-0

Our eBooks may be purchased in bulk for promotional, educational, or business use. Please contact the Macmillan Corporate and Premium Sales Department at 1-800-221-7945, extension. 5442, or by e-mail at .

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021939500

Cover and book design by Rosie Stewart for Page Street Publishing Co.

Photography by Bernadette Banner

Additional design elements from Shutterstock and Creative Market

Dedication

For Bertha Banner (no relation)

Introduction

The realization has occurred to me that, for all the sewing projects I have documented online, rarely do I take a moment to stop and explain the basics: how to start and end the thread, why Ive cut pattern pieces in certain directions and what is meant by such words as bias and fell. So, while it has become fairly clear over the years that the online videos are meant primarily as mainstream entertainment and something nice to look at, if you actually want to know the gritty details, you will probably require something a bit more practical. And so, here we are. Its weird seeing you here in this strange new format, but were going to have a good time.

This whole online hand sewing business began as a personal endeavor to learn more about the history of humans through an attempt to reconstruct the clothes that they wore. But very quickly I began to understand that, despite the technological advancements that now make certain aspects of modern society easier and more efficient, sometimes that efficiency develops to a fault: Modern manufacturing favors speed over craft, quantity over quality. Just because we do things faster or cheaper or with fancy machines nowadays doesnt necessarily mean that we do things betterand indeed, the definition of the word better, in this case, is neither an objective one, nor does it qualify a singular goal. Certainly our capability for mass production today is better, but speed often results in a sacrifice of quality; cheapness, a sacrifice of fair worker compensation and quality of material; overproduction, a sacrifice of mindful consumption. In our efforts to progress into better, the 21st century has seen the explosive rise of a trillion-dollar fashion industry responsible for more greenhouse gas production than all the shipping and aviation industries combined.

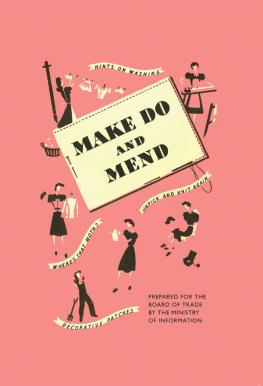

None of this is to say that the textile industries in the centuries before our present one were perfectthe issue of underpaid garment workers is certainly nothing new to modern fast fashion. The discrepancy between the labor involved in the production of good-quality clothing and the price many people are able to pay, coupled with the stigma in recent centuries that sewing is womens work and thus of lesser value, has never been a problem fully resolved. But here lies the advantage of the present: We have the ability to pick out from the past all the things that did work, whilst examining those that didnt, and adjust our solutions accordingly. This has since become a habit of mine, when in need of a solution to a problem: to look back at the long list of solutions to similar problems that history has already laid out for us. What similar struggles did our ancestors face, and what solutions were devised? What can we learn from the methods, trials, experiments, mistakes and successes of the past, so as to solve our own problems more thoroughly and efficiently? The quantity of data we have for forming new solutions is greater now than it has ever been.

In the days before mass manufacture, clothing tended to be obtained in one of three wayseither it was self-made, was made for the wearer by another person (whether family or on commission from a dressmaker or tailor) or obtained secondhand, be that through purchasing, trading or handing down amongst family members. It wasnt until the Industrial Revolution in the mid-19th century that western Europe and North America began seeing the normalization of clothing produced in standard sizing on a mass-manufacture scale, made by workers trained in small portions of the manufacturing process and who would never come into contact with the wearer. Even so, the scale of mass manufacture tended to be of a regional or national capacity rather than the global levels of distribution that mass-manufactured products experience today. Conscious attitudes toward the purchasing of new clothing, even in the form of ready-to-wear, carried through into the 20th century. One 1916 home manual instructs its readers that Each garment in ones wardrobe, or the materials for its construction, should be selected with the following consideration:

1. The need for its purchase;

2. The use to which it must be put;

3. Its durability;

4. Its suitability to the wearer;

5. Its cost in relation to the allowance.

This advice on purchasing clothing responsibly is provided alongside practical sewing, mending, patterning and maintenance advice, implying that the consumer of ready-to-wear garments was still expected to have an understanding of how clothing was mended and made.

Apart from the very upper classes, who could afford to wear a gown only once or twice, there was no expectation that new clothing had to be bought by the season or that outfits couldnt be repeated multiple days in the week. This was, granted, slightly obligatory due to the amount of labor required of hand weaving and hand making clothes, particularly in the preindustrial eras, so each garment was inherently more costly. Most people knew how to sew, or knew someone who knew how to sew. Clothing wasnt made by invisible hands in faraway lands as is much of our clothing in Western society today, meaning that, historically, the labor required in garment production was inescapable in the mind of the wearer. This absence of societal expectations and pressures toward consumption, particularly of fashion and textiles, laid the groundwork for a lifestyle operating on slow rather than fast fashion.