An Artist's Letters from Japan

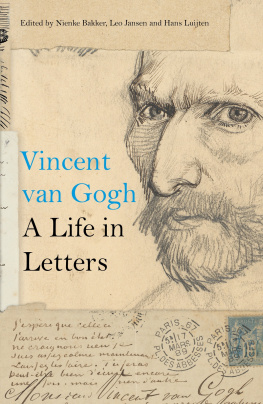

Written by the doyen of American impressionist painters, La Farge, during his travels in Japan with Henry Adams in the latter part of the nineteenth century, writes with amazing sensitivity and observation about the whole of Japanese society at that time. John La Farge was born in New York in 1835 to a wealthy and artistic family of French descent. He studied art in Paris and then with William Hunt at Newport, Rhode Island. However, he had a unique and complex mind capable of immense subtly. He studied Japanese wash painting and mastered Mandarin Chinese. He also invented the process later known as Tiffany Glass.

JOHN LA FARGE was a painter, writer and traveller.

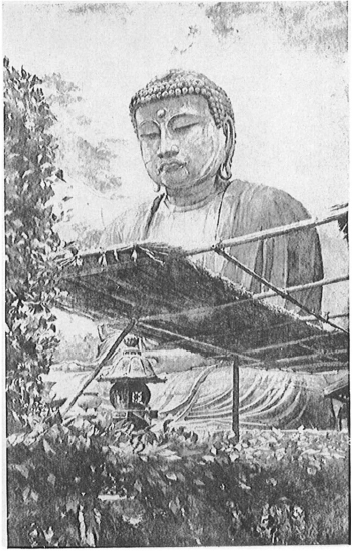

THE GREAT STATUE OF BUDDHA AT KAMAKURA

AN ARTIST'S LETTERS

FROM JAPAN

BY

JOHN LA FARGE

LONDON AND NEW YORK

First published in 2000 by

Kegan Paul International

This edition first published in 2010 by

Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

270 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Kegan Paul International, 2000

Transferred to Digital Printing 2010

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 10: 0-7103-0690-3 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-0-7103-0690-6 (hbk)

Publisher's Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent. The publisher has made every effort to contact original copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

TO HENRY ADAMS, ESQ.

My Dear Adams: Without you I should not have seen the place, without you I should not have seen the things of which these notes are impressions. If anything worth repeating has been said by me in these letters, it has probably come from you, or has been suggested by being with you perhaps even in the way of contradiction. And you may be amused by the lighter talk of the artist that merely describes appearances, or covers them with a tissue of dreams. And you alone will know how much has been withheld that might have been indiscreetly said.

If only we had found Nirvana but he was right who warned us that we were late in this season of the world.

J. L. F.

WHICH IN ENGLISH MEANS I

AND YOU TOO, OKAKURA SAN : I wish to put your name before these notes, written at the time when I first met you, because the memories of your talks are connected with my liking of your country and of its story, and because for a time you were Japan to me. I hope, too, that some thoughts of yours will be detected in what I write, as a stream runs through grass hidden, perhaps, but always there. We are separated by many things besides distance, but you know that the blossoms scattered by the waters of the torrent shall meet at its end.

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

THE GREAT STATUE OF BUDDHA AT KAMAKURA.

AN ARTIST'S LETTERS FROM JAPAN

AN ARTIST'S LETTERS FROM JAPAN

YOKOHAMA, July 3, 1886.

A RRIVED yesterday. On the cover of the letter which I mailed from our steamer I had but time to write: We are coming in; it is like the picture books. Anything that I can add will only be a filling in of detail.

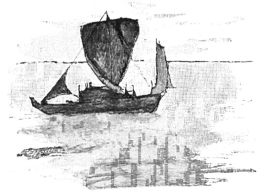

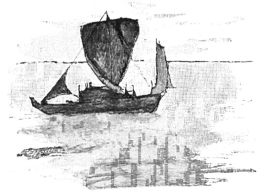

We were in the great bay when I came up on deck in the early morning. The sea was smooth like the brilliant blank paper of the prints; a vast surface of water reflecting the light of the sky as if it were thicker air. Far-off streaks of blue light, like finest washes of the brush, determined distances. Beyond, in a white haze, the square white sails spotted the white horizon and floated above it.

The slackened beat of the engine made a great noise in the quiet waters. Distant high hills of foggy green marked the new land ; nearer us, junks of the shapes you know, in violet transparency of shadow, and five or six war-ships and steamers, red and black, or white, looking barbarous and out of place, but still as if they were part of us; and spread all around us a fleet of small boats, manned by rowers standing in robes flapping about them, or tucked in above their waists. There were so many that the crowd looked blue and white the color of their dresses repeating the sky in prose. Still, the larger part were mostly naked, and their legs and arms and backs made a great novelty to our eyes, accustomed to nothing but our ship, and the enormous space, empty of life, which had surrounded us for days. The muscles of the boatmen stood out sharply on their small frames. They had almost all at least those who were young fine wrists and delicate hands, and a handsome setting of the neck. The foot looked broad, with toes very square. They were excitedly waiting to help in the coaling and unloading, and soon we saw them begin to work, carrying great loads with much good-humored chattering. Around us played the smallest boats with rowers standing up and sculling. Then the market-boat came rushing to us, its standing rowers bending and rising, their thighs rounding and insteps sharpening, what small garments they had fluttering like scarfs, so that our fair missionaries turned their backs to the sight.

Two boys struggling at the great sculls in one of the small boats were called by us out of the crowd, and carried us off to look at the outgoing steamer, which takes our mail, and which added its own confusion and its attendant crowd of boats to all the animation on the water. Delicious and curious moment, this first sense of being free from the big prison of the ship; of the pleasure of directing one's own course; of not understanding a word of what one hears, and yet of getting at a meaning through every sense; of being close to the top of the waves on which we dance, instead of looking down upon them from the tall ship's sides; of seeing the small limbs of the boys burning yellow in the sun, and noticing how they recall the dolls of their own country in the expression of their eyes; how every little detail of the boat is different, and yet so curiously the same; and return to the first sensation of feeling while lying flat on the bottom of the boat, at the level of our faces the tossing sky-blue water dotted with innumerable orange copies of the sun. Then subtle influences of odor, the sense of something very foreign, of the presence of another race, came up with the smell of the boat.