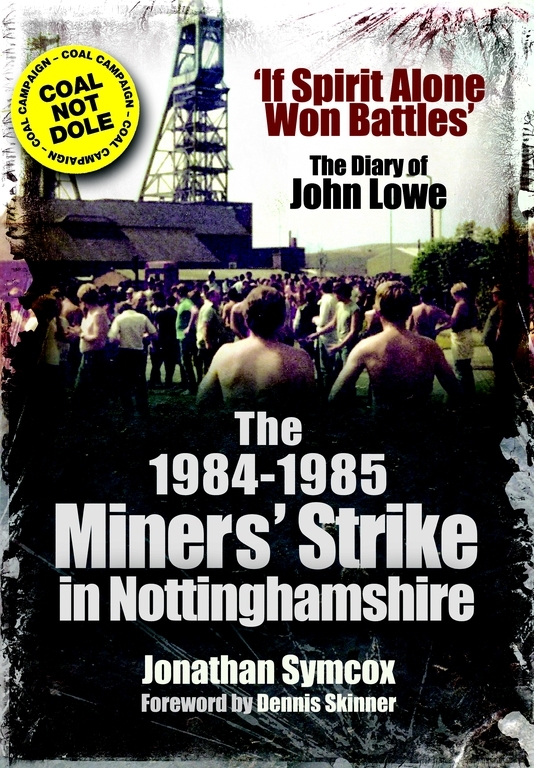

First published in Great Britain in 2011 by

Wharncliffe Books

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright John Lowe and Jonathan Symcox, 2011

9781783408856

The right of John Lowe and Jonathan Symcox to be identified as Authors of this Work

has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents

Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or

by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any

information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in

writing.

Typeset in 10/12pt Century by

Concept, Huddersfield, West Yorkshire

Printed and bound in England by

CPI UK

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword

Family History, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Pen & Sword Discovery,

Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe True Crime, Wharncliffe Transport, Pen &

Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics, Leo Cooper, The Praetorian Press,

Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

FOREWORD

by Dennis Skinner MP

I knew John Lowe growing up and as a young man in Clay Cross. I passed him thousands of times in the street, going to work, coming back from work, going to a council meeting, going for the paper, doing this, doing that. But I cannot recall talking with him politically, except regarding the local elections. Have you been, John? Have you voted? Id ask. And hed nod and say: Yes, you know I have. But that was it.

We went our separate ways, as happens. He went to live in Nottinghamshire to work and I thought no more about it. Then years later, in 1984, the national miners strike began and I came across him again. He may well have been active in the miners victorious strikes of the 1970s, but they were very short, six or seven weeks. This one was to be different. Early in the dispute I did a big meeting at Worksop set up principally to try and galvanise the local NUM forces in Nottinghamshire. And there was John Lowe and he wasnt just a member of the crowd! He was asking questions, making speeches... I had to say to someone: is that the same fella? And the reply was yes!

It was a revelation to me because for the rest of the strike and way beyond John Lowe was one of six or a dozen key figures in Nottinghamshire. He was there at everything. After the strike he would organise the Black and Gold at places like Rainworth and Blidworth and all over. If I was to be asked whether people could turn into giants, politically and industrially, as a result of a battle with the management and the Government and the police... I would put him in my top ten of those people. I rate him exceptionally highly. Most people who got involved in the leadership of the strike you could have named before the event. Ida Hackett we all knew shed be kicking the ball about. Sid Richmond he was waiting for it. It was made for him! And various others I could mention. But you would not have named John Lowe. Yet when it began, he was on the front row.

I cannot say with certainty that he was transformed by events: it may have been latent, there all the time, and he was just waiting for the day, for the year and those that followed to bring it out. There are surprising people in all walks of life that become strong when things are exceptionally difficult. I could give examples of people in the Bolsover area, but not as sharply distinctive as John Lowe, he that I knew as a miner in Clay Cross and who then became a leader for several years in the most difficult coalfield in Britain. He shone out among the others in terms of being a discovery.

Believe me, it was hard in Nottinghamshire. You had to be strong to survive: in many of those pits there were more people in work than there were on the picket line. Picketing there was for real: they were trying to stop their friends erstwhile friends and, I suppose, some enemies from going through the picket line day after day, after day. While the Government and everybody else regarded the scabs as decent, honest, genuine people who should be allowed a free route to get to work, this relatively small band of folk were doing the honourable, principled thing of being prepared to eat grass rather than give in. They are not given honours, OBEs and the like, for their gallantry; but if they were handed out to such people on that side of the political fence, John would have been a recipient, without a doubt. But hed tell you he didnt believe in the system anyway.

Much of the Notts workforce came from other areas of the country. It was very significant during the strike that pits like Cotgrave, dominated by those from the North East, could not emulate what their colleagues were doing up there; and yet I remember opening a gala at Cotgrave long before the strike and they were running the whippets and everything else it was like a little bit of Durham. But they acted like Notts miners, not Durham miners, at the end. Those leading the fight at National level always knew Notts might renege upon what the rest of us were doing, as they had in the old days in the General Strike of 1926, so we had to concentrate upon the county. I know that John believed that Spencerism was still prevalent: they were not only dealing with the present situation, but also the history. The Notts coalfield, generally speaking, made a lot of money: as it was newer than the others, at most pits you did not have to go so far out to fetch the coal as in the other areas. The colliers there used to get wages that were a little bit above the odds. All this meant that they thought they were the bees knees indispensable. And yet it wasnt about that. The working miners in Notts were promised the moon, and look at it now: I think theres one pit left. So what was it all for? John and others were trying to convey that message the best way they could; they certainly werent telling lies and they were treated like shit, even when it was over. So even though Notts was one of the newest coalfields in Britain, with pits that had a longer life than almost anywhere else in Britain, it has now almost entirely disappeared. Thats the price the scabs paid.

The county is now like any other struggling former mining area: that economic power from the pits and the big manufacturing base around Nottingham has disappeared. The erosion of the Labour vote, the fragmentation which has led to the election of tin-pot mayors and all sorts, could not have taken place had the strike not been lost. Im sure of that, because victory has a special glow about it. It makes you feel good. And wed still have the pits. My constituency had a few thousand that worked over the border in Notts while there were also several thousand on strike. I still see a lot of them when they have a problem, be it housing, social security or whatever. I deliberately raise the strike, even today, in order to see what their reaction is and many of them prefer to not enter that specific part of the discussion, and move the subject on to something else. They would rather not reflect on what happened.