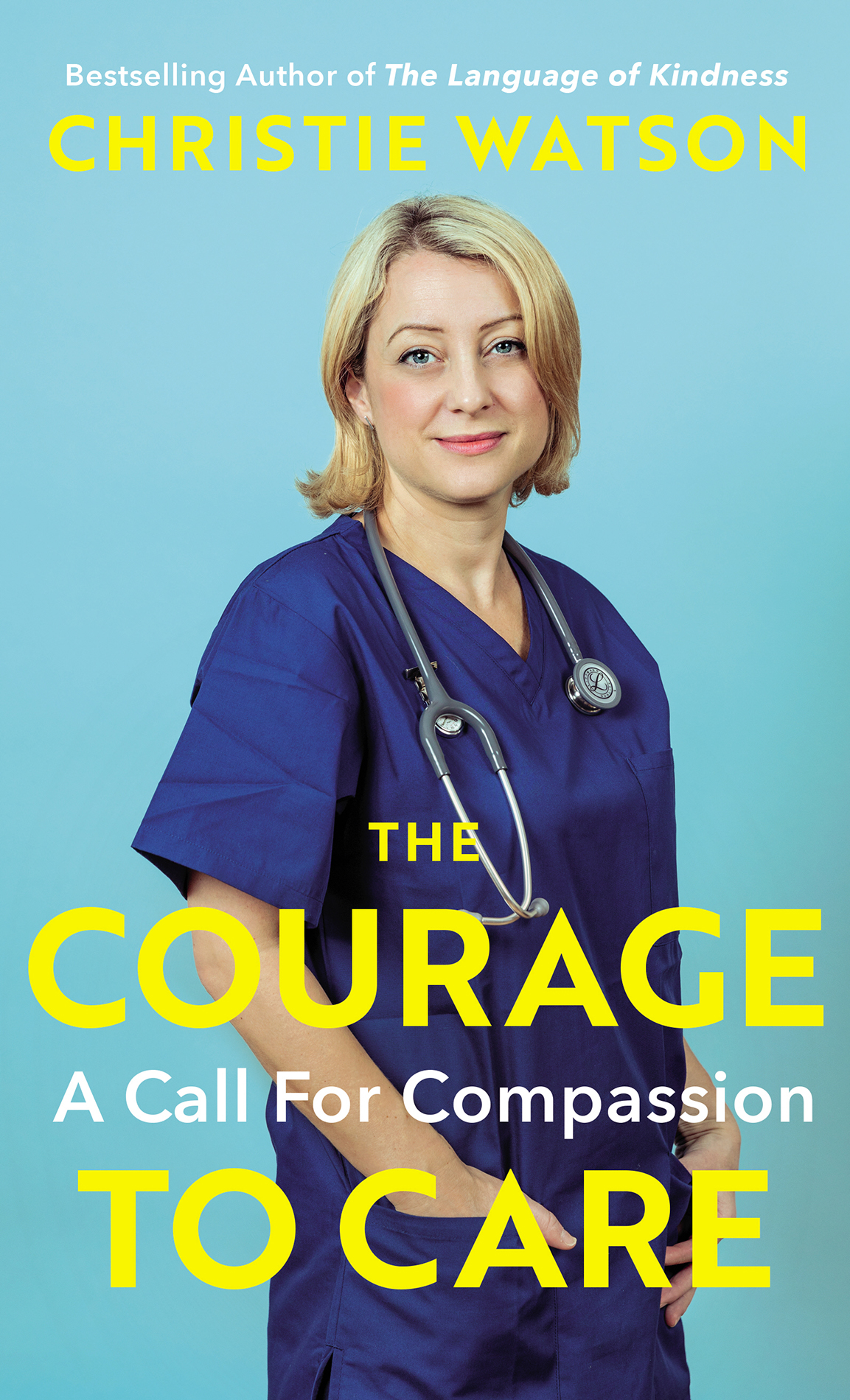

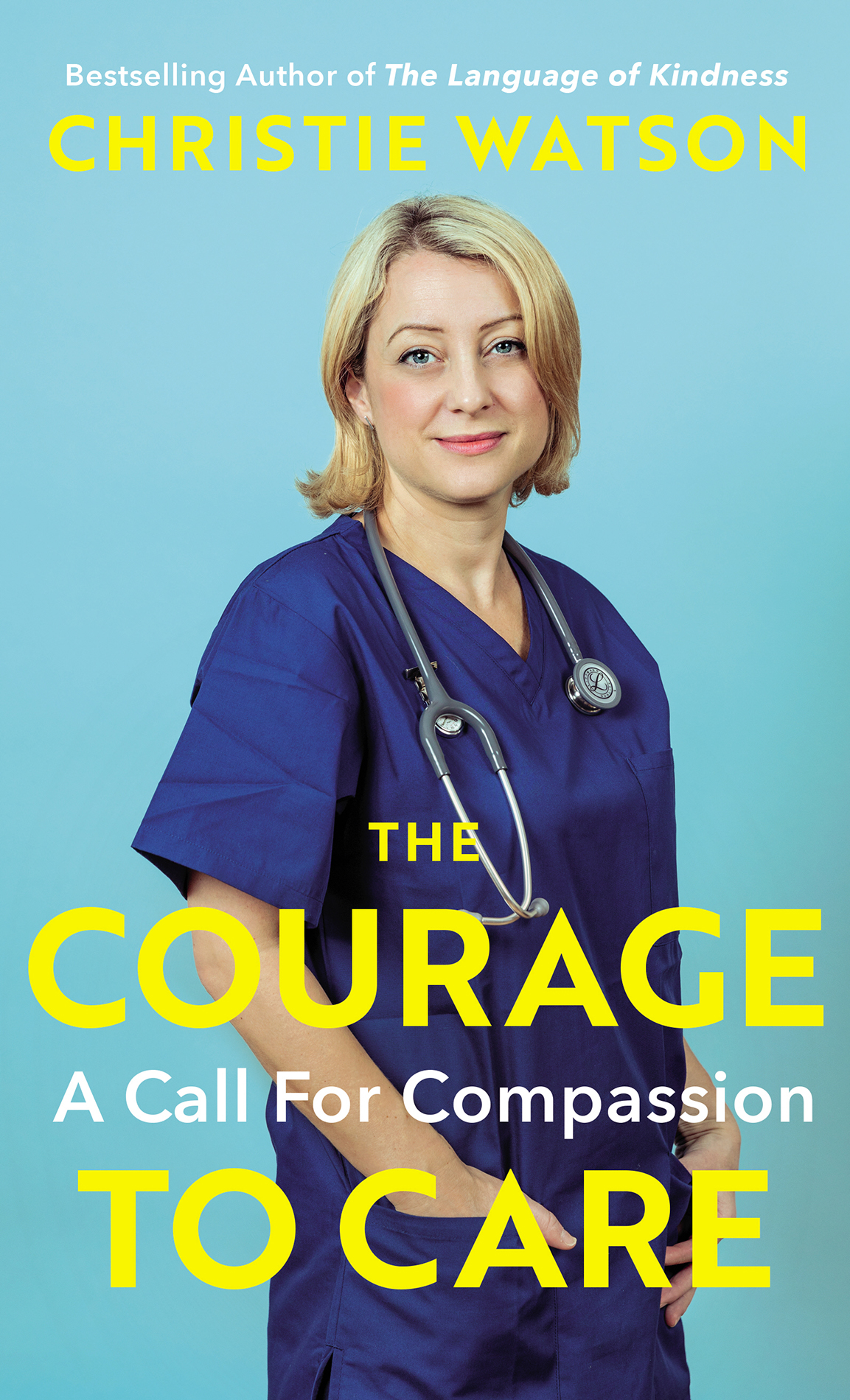

Christie Watson

THE COURAGE TO CARE

A Call for Compassion

Contents

About the Author

Christie Watson is an award-winning, bestselling writer. She has been a nurse for over twenty years.

The Language of Kindness was published in 2018 and was a number one Sunday Times bestseller. It was a Book of the Year in the Evening Standard, Guardian, i, New Statesman, the Sunday Times and The Times. It has been translated into 23 languages, and is currently being adapted for theatre and television.

Her first novel, Tiny Sunbirds Far Away, won the Costa First Novel Award and Waverton Good Read Award and her second novel, Where Women Are Kings, also achieved international critical acclaim.

Christie holds an honorary Doctor of Letters for her contribution to nursing and the arts and is Patron of the Royal College of Nursing Foundation. She is Professor of Medical and Health Humanities at the University of East Anglia.

www.christiewatsonauthor.co.uk

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Non-Fiction

The Language of Kindness

Fiction

Tiny Sunbirds, Far Away

Where Women Are Kings

For the Families of Nurses

I know youre tired, but come. This is the way.

Rumi

Authors Note

The events described here are based on memories of my experiences as a nurse. Identifying features have been changed in order to protect the privacy of colleagues, patients and their families, and descriptions of certain individuals and situations have been merged to further protect identities. Any similarities are purely coincidental.

Introduction

The Language of Kindness, my previous book, focused on my experiences, primarily as a hospital nurse, in uniform. But there is a whole world of nursing outside hospitals, spanning the length and breadth of our country, and countless nurses voices which deserve to be heard. I spent two years writing The Courage to Care and was lucky enough to travel widely, meeting nurses from all walks of life, and hearing about their incredible work. I wanted to write about exceptional nurses everywhere, in every setting, and the difference they make to the lives of colleagues, patients and families, including my own.

I have been talking and writing about the importance of nurses for many years: how undervalued they have been; how overworked and underpaid; and underlining just how vital nurses are to society. But of course, I had no idea what was to come. None of us did. I was making final edits to The Courage to Care when COVID-19 changed the world, perhaps forever.

This is a time of profound reflection for all of us. We must pause and mourn, and grieve for those who have died during this awful virus. Perhaps we can continue to honour them and all those frontline workers who lost their lives for us by taking care of our neighbours, our communities, and the vulnerable, including those who are unable to work and those who are no longer working. Those in need. People have been thinking of other families, as well as their own. We must hold onto that: the courage to care. Compassion for others is how we will be judged. And it is how we should be judged. This is a time for all of us to think about community, how delicate life is, and what life now means. We will be changed by this, all of us. And the search for meaning has only just begun.

I had no idea how poignant and timely this book would be. Nurses have always been at the forefront of society, and that, perhaps, is finally being acknowledged. It is nurses who are saving lives during all of this, and the lack of critical care nurses has been one of the most significant challenges. It is nurses who are holding the hands of our loved ones as they are dying, who are with them when we cant be there, reminding us that we are never alone, not even now. And it will be nurses who bear the weight of COVID-19 long after the peak. Because, for those who survive, this is just the beginning. The level of support, rehab and expert care needed by so many people is almost unimaginable, and the fallout for those who have suffered due to the impact of COVID-19 with other illnesses and diseases is beyond measure. Those with cancer, long-term conditions, mental illness. An entire generation of children. Our elderly. Nurses have always fought for social justice and human rights, and COVID-19 has shown up the vast inequalities and discrimination across our country. It will be those who already suffer most who will suffer more, and nurses will care for and champion them, regardless.

Yet nurses predominantly women remain undervalued even now.

The absence of any nurse on the COVID-19 SAGE advisory panel, for example, is or should be, surely unacceptable to all of us. The reason, I am told, is that SAGE is made up of scientists.

But, of course, nurses are scientists. And writers. And academics and philosophers and leaders and researchers and artists and experts and technicians and practitioners and innovators and entrepreneurs and influencers and statisticians and workforce modellers and expert witnesses and advanced practitioners and crisis managers. Nurses are consistently cited by the public as the most trusted profession.

It is high time that nurses of every background have a seat at the political table for all our sakes. Nurses have never been more important.

6 July 2020

1

A Shrinking Satsuma

My daughter. She is here. Curled up in a hedgehog ball, but softer than anything in the universe. Not wanting to miss a blinks worth of time, I gaze at her face, her pouting mouth, the way she frowns, yawns. Her shell-ears. She is born with a quiff of thick black hair and an expression that says shes been here before. A knowing, testing look. Her eyes are such dark brown that it is only when I tilt her into the pale light from the window slats, letting it stripe across her face, that I see they are not black. Her skin is shockingly white, but the maternity support worker, Mary, laughs and holds up my daughters tiny hands, shows me her fingernails. She will soon change she says. Look. And her nailbeds are dark, the colour I expected her to be, with a black dad, white mum.

That she is born whiter than I am is not my only shock. She has a large Mongolian spot on the base of her spine, a congenital dermal melanocytosis, a type of birthmark. It is purple-grey, the colour of an old bruise and the size of a satsuma. She is early, and small. The midwife tells me its nothing to worry about, but worry is born when she is. Ive read research that suggests Mongolian spots are not, as previously thought, always benign. They can be associated with metabolic disorders, and with other diseases and conditions. I try to explain this fear that I feel in my stomach and throat and hair to the midwife, the cleaner and, finally, to Mary, who brings me lukewarm sweet tea and two gingernut biscuits. But its hard to put into words. Maybe she is seriously ill? Perhaps I am being irrational? I begin assessing my baby as if shes one of my intensive-care patients. I check her reflexes, pupil reaction, respiratory rate and capillary-refill time.

Next page