Contents

Guide

Page List

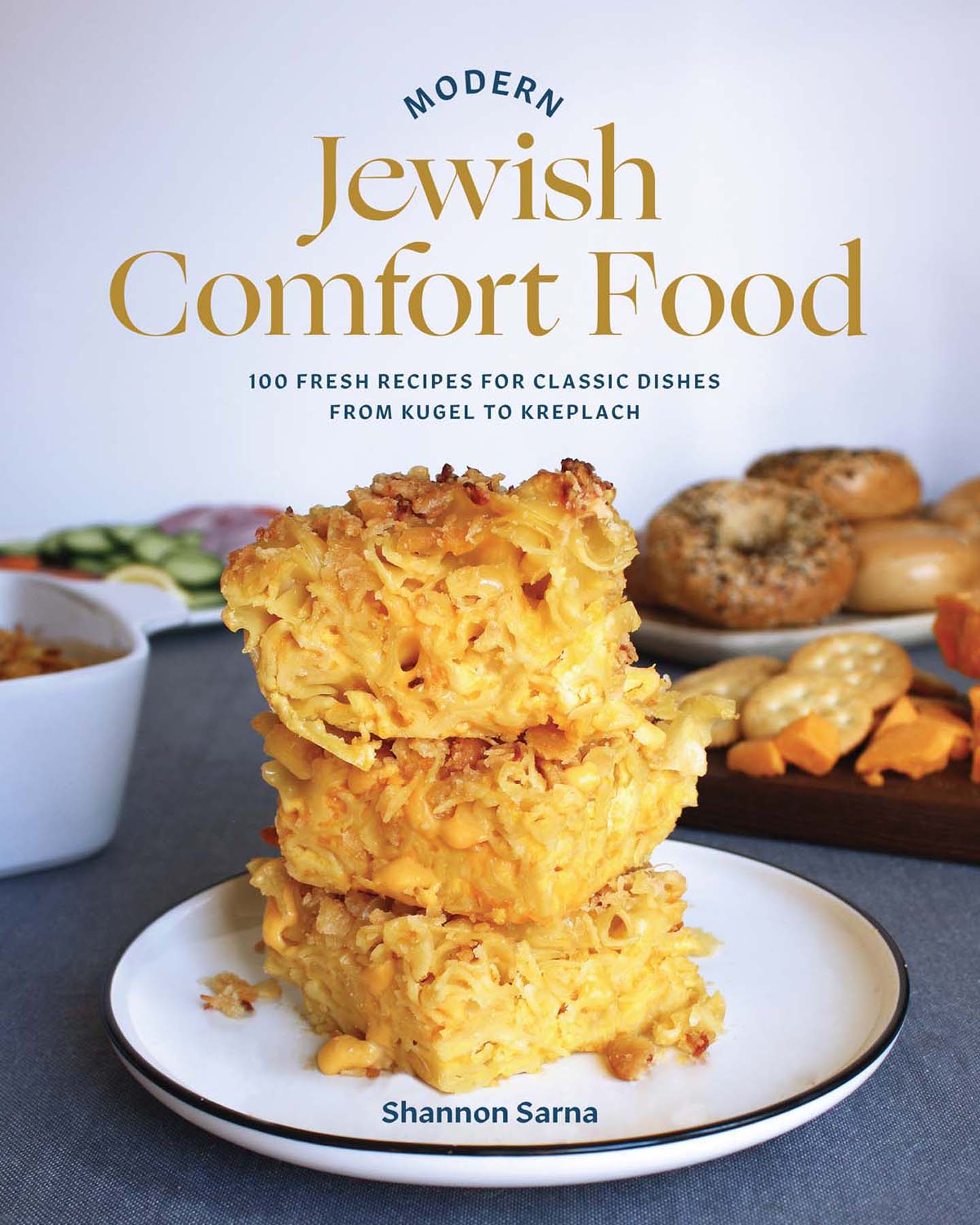

MODERN Jewish Comfort Food 100 FRESH RECIPES FOR CLASSIC DISHES FROM KUGEL TO KREPLACH Shannon Sarna Phototography by Doug Schneider Styling by Sheri Silver

To Bubbe Phoebe

Contents

If you are going to follow links, please bookmark your page before linking. Comfort food is completely subjective; it varies person to person, family to family, and region to region, even among Jewish families. F or me, the ultimate comfort food is a steaming bowl of egg noodles, lightly buttered with a big dollop of cottage cheese on top and tons of black pepper. Its what my father used to feed me for lunch on Sundays, because its what his grandfather used to feed him. Its also my mother-in-laws favorite comfort food, one that her own grandmother fed her, and now it is my daughters favorite, too. For many, this combination may seem bizarre, but for families with Polish heritage, the dish is likely familiar.

Its peasant food: simple, cheap, and completely satisfying. Its the dinner we throw together when theres nothing else in the fridge. Its beloved not only because its delicious but because of the story it tells. In Poland, it contained homemade egg noodles and pot cheese. In America, it received an easier upgrade with store-bought noodles and the more widely available cottage cheese. Some families make it sweet with a little sugar and cinnamon; others, like mine, keep it savory, but it is a common taste of home for families whose great-grandparents, or great-great-grandparents, came over from Poland.

This is merely one vignette of comfort food from American-Jewish-Polish families. What is so enthralling about Jewish comfort food is that its not a monolith. For Jews from around the world and diverse backgrounds, it means many things and tastes vastly different, but has a few common threads that tie it together: it tells the story of where we have been, our struggles as a people, and how we have persevered. To say this more simply, the story of Jewish food goes something like this: We were poor, we didnt have a lot, so we threw what scraps we had together and the result was delicious. And by the way, this isnt just the story of how Jewish comfort foods came into existence. This is a theme that runs throughout comfort foods from around the world.

As I discovered while growing up half Italian American and half Jewish American, the commonalities between Jewish food stories and Italian food stories (as well as among other cuisines) tell many similar tales of creating deliciousness from very little. The Jewish people have lived in or been exiled to wide-ranging lands all over the world, which tells a diverse story of our people and foods that have been adopted and adapted by them. Joan Nathan has explained that there isnt so much Jewish food, as a way of Jewish cooking that has adapted to kosher dietary laws and local cuisines wherever Jews have settled, which is why its so difficult to succinctly explain what exactly Jewish food looks and tastes like: it is so very many things. Lets take a few minutes to review some Jewish history, and how it has shaped Jewish cuisine. There are four categories of Jewish people whose lands and histories deeply impact their customs and foods: Ashkenazim, hailing primarily from eastern Europe, Germany, and northern France; Sephardim, Jews of Iberia who were part of the Spanish diaspora (i.e., kicked out during the Spanish Inquisition, which has included Greece, Italy, the Balkans, North Africa, Turkey, and many countries in South America and the Caribbean); Mizrahim, who hail from Middle Eastern countries and who often lived side by side Muslim and Christian neighbors for thousands of years; and Ethiopian Jews, who had been almost completely isolated from other Jewish communities until the 1980s, and so have very special, unique customs. The majority of American Jews hail from Europe, and with such large waves of Jewish immigrants from Hungary, Germany, Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, and Russia at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, a brand-new Jewish cuisine emerged from Manhattans Lower East Side, and other immigrant enclaves around the United States.

Deli culture, bagels and lox, and sugar-laden noodle kugels made a deep impact on the ways Jews would cook in America, and also how non-Jewish Americans would define Jewish food. The stereotypes of matzah ball soup, knishes, and brisket, however, doesnt tell the entire story of Jewish American immigration, and leaves out later waves of immigrant communities from Syria, Iran, Greece, and other parts of the Middle East. The creation of the state of Israel in 1948, and the waves of immigrants who made it their new home, deeply influenced the next chapter of Jewish food. Immigrants from Europe but also many Middle Eastern and North African countries brought their own comfort foods with them, which became part of an evolving new cuisine: flaky Yemenite breads, such as malawach, kubaneh, jachnun, and their rich complementary soups; Iraqi meat-filled kubeh dumplings and the traditional eggplant, potato, and egg breakfast that became the popular sabich sandwich; thinly pounded, German-style schnitzel; and Palestinian chopped salads and creamy hummus converged and evolved into a new and very dynamic cuisine. Due to the nature of our global economy today and social media, that new Israeli cuisine has been catapulted around the world, embraced by home cooks and chefs, Jewish and non-Jewish, Israeli and non-Israeli alike. It has changed the way Jews everywhere eat and think about food.

We now see that Jewish food can be stuffed cabbage and stuffed zucchini, schmaltz and tamarind, brisket and schnitzel, street knishes and homemade sambousek. Jewish comfort food encompasses so many things. Comfort food may mean something different to every community, but it is, ultimately, the smells, sounds, and memories of being in the kitchen. For my Syrian Jewish friends, its spinach jibn for a weekday breakfast, leek patties freshly fried for Rosh Hashanah, and kibbeh on Shabbat. For my Israeli Jewish friends, it means chocolate hazelnut swirl cookies with afternoon tea, shakshuka on busy weeknights, and stuffed peppers for Shabbat dinner. For my own American Jewish family, it is a big slice of noodle kugel at Yom Kippur break-fast, chicken soup with matzah balls and lots of dill on Passover, and sweet-and-sour meatballs just because.

Chef and TV host Pati Jinich once told me that if a cuisine doesnt evolve, it dies. Jewish food continues to shift, expand, and reinvent itselfand its thrilling to live in a time where people are excited to eat, enjoy, and talk about it. As editor of The Nosher for the past 10 years, it has been my daily goal to tell the story of the Jewish people through food and I take this responsibility seriously in that job, and in presenting this book. One of the pieces of feedback I hear again and again about my book Modern Jewish Baker is that the clear instructions, visuals, and recipes give people confidence to tackle baking projects theyve never tried before. This served as inspiration for

MODERN Jewish Comfort Food 100 FRESH RECIPES FOR CLASSIC DISHES FROM KUGEL TO KREPLACH Shannon Sarna Phototography by Doug Schneider Styling by Sheri Silver

MODERN Jewish Comfort Food 100 FRESH RECIPES FOR CLASSIC DISHES FROM KUGEL TO KREPLACH Shannon Sarna Phototography by Doug Schneider Styling by Sheri Silver

To Bubbe Phoebe

To Bubbe Phoebe