Ken O’Sullivan - Stories from the Deep

Here you can read online Ken O’Sullivan - Stories from the Deep full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Gill, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Stories from the Deep

- Author:

- Publisher:Gill

- Genre:

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Stories from the Deep: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Stories from the Deep" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Stories from the Deep — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Stories from the Deep" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

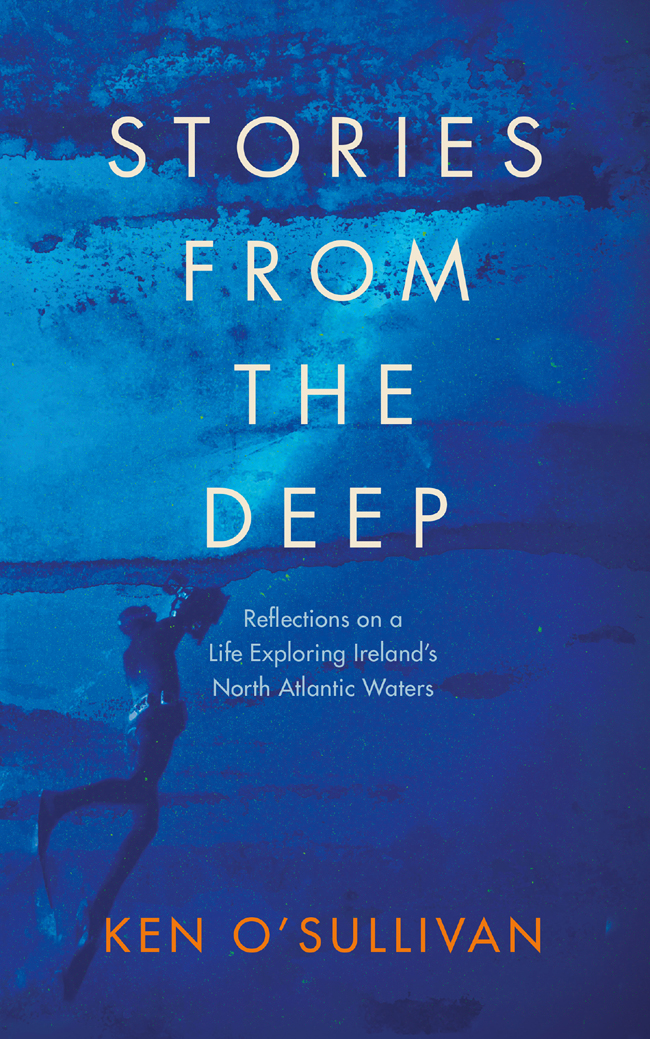

STORIES

FROM

THE

DEEP

Reflections on a

Life Exploring Irelands

North Atlantic Waters

KEN OSULLIVAN

Gill Books

To my mother Rita Garvey, and my sisters

Catherine, Margaret, Marie and Eleanor,

strong women who sustained us all.

To our dear brother Liam, too beautiful

for this world.

For

Katrina, Eimear, Jill & Aishling,

lights that will keep shining.

Thanks to:

Mike Hilliard Mulcahy

Jim Cooney

Tom Mulcahy

John Richardson

Conor Nagle at Gill Publishing

Michal Cinnide

Gay Cooke RIP my English teacher

And all the pain we suffered which led us

reflect and create, and without which we

might have been more balanced,

contented people.

Contents

THE SEA AND ME

MY MOTHER TOLD ME I was born dehydrated. Her waters had broken well before my delivery, You looked so dried out, almost dishevelled, she told me fondly. Ive always loved water. One of my earliest recollections is being bathed in the porcelain kitchen sink in our old house in Ennis, laughing as my mother poured jugs of warm water over my head and me splashing and loving the droplets of water slipping through my tiny hands.

I grew up swimming in the Turret, a pool in the River Fergus on the outskirts of town. There were diving boards there, but the council took them down, probably after being sued by someone. So we climbed the trees on the riverbank and jumped in from there. I remember midnight summer swims, six or seven of us skinny-dipping in the dark and just laughing at the sheer joy of it.

In my last January there, I cycled to and from school across a bridge overlooking the Turret. I watched the swollen winter river gurgle up like a dark, devilish volcano, troubled waters it seemed to reflect my failing exam results and the worry and pressure I was under, a few months before the torturous life-defining exam every Irish teenager has to face.

Summer was golden. Warm evenings in the Turret when everyone was in good form, I watched a fella a year older than me, whod just finished school, swim across the river, lay back and rest on shallow sunken rocks under the trees. God, I wished that was me, another year of that shite. I hated school from day one, and it never leaves you, I still have nightmares about that exam, its the night before the Leaving Cert Irish and Ive nothing done, its terrifying, I wake up in a sweat. But my time eventually came around and I swam triumphantly across the river to rest in the warm shallow water of a golden July evening.

Then there was the sea. My father would pack what seemed like six or seven of us into a car and wed drive the twenty-one miles to Lahinch. Maybe because we only went a few times a year, these were the really special days. There are a couple of small hills on the road as you approach Lahinch, wed be bursting with anticipation, and over the years someone came up with a game of who could see the sea first as we rose up the last hill, to steal a distant glance at the blue Atlantic horizon, I see the sea, No you dont, as if the excitement werent already enough.

At first the sea is freezing, we wail and jump, arms wrapped around ourselves inching into deeper water. Teeth chattering, sinking cautiously into the bracing waves, then more screams. And in no time weve forgotten the cold, jumping over waves and splashing each other for what seems like hours, then were in the reverse situation of not wanting to embrace the land, just another few minutes, ple-eee-ase.

I remember salty faces and hair and sandy toes as we piled back into the car. On the way home wed stop a couple of miles along the road in Ennistymon for canned sweets boiled glassy sweets that an old woman would fill into brown paper bags, sixpence-worth please, and back in the car wed doze on the soft, briny tiredness that only the sea brings. The sea stays with you.

My father came from Fenit Island, Co. Kerry, where our family had lived since about 1750. I was fortunate to spend the summers of my youth there in what I can only describe as a Huckleberry Finn-type existence, because on Fenit Island, we had the sea every day.

When I was ten or eleven years old and I had just got the fishing bug, most things in my world were things that got in the way of just being on the rocks at Bal Gheal, Oilain na Choise or Cloichn or any of the other colourful place names thought up by my ancestors for the fishing spots around the island. Approaching the shore on the back of my uncles small red tractor, there was only one word I dreaded, swell. As the sea came into view, with a black foreboding sky bearing down on it, I could see the slow, deliberate rise of darkened water engulfing the rocks and the ensuing gurgling of white water. Shaking his head, my uncle said the dreaded word, swell too much swell today, boy. Its funny how a word can conjure up so much imagery. When my father stood watching the sea and sombrely used that word, I understood about the people who had drowned here on our island.

You see Irish coastal folks had mastered so much of surviving on the seashore; they became expert fishermen, if only on a subsistence scale. Some of the earliest evidence of human presence in Ireland has been found on our shores; Ive found 6,000-year-old shell middens on the Clare coast with thousands of limpet shells and a black cooking stone. But getting into the sea was not something these folks did well; they just couldnt.

I spent much of my teenage summers on Fenit Island with my father, fishing, pulling trammel nets out of freezing pre-dawn waters, and picking periwinkles and carrageen, which wed then sell in Tralee. Hard work, but it brought a great sense of purpose, of harvest and subsistence and self-dependence. In my experience, rural farm folk but most especially island people had an incredible ability of self-reliance: they could make almost anything they needed, simply because they had to, and perhaps those who couldnt didnt survive or left. We slept in the airy rooms of my uncles farmhouse, which smelt of well, farm, and salty air, under covers made of cotton washed ashore in the 1920s from a shipwreck and made into quilts by my grandmother long before we knew what a continental quilt was. They were still in use when my uncle Jack, the last of our kind on Fenit Island, died in 1994.

There was a deep sense of peace and calm to island life, everything slowed down, and time was dictated only by the morning and evening milking of cows and the stages of the tide. My uncle Den would ask me to check the paper to see what time high water was today, if he had to go to town, the mainland could only be accessed across the strand at low tide. My father had, on retirement, returned to the seashore of his own youth, to do the things he had done with his father back in the 1920s and 30s, ancient fishing methods and local knowledge handed down.

Compass jellyfish off the Clare coast

He bought a trammel net and mounted it, running ropes through the bottom and top rows of mesh. Three-inch tubular lead weights were placed on the bottom rope and squeezed in place with large pliers, floats were placed about every half yard on the top row. Wed tie rocks onto the ropes at either end of the net and at low tide row out into maybe a fathom of water. My father would slowly feed the net out from the back of the boat as I rowed parallel to the shore until we reached the end of the net, which was over a hundred yards long before mounting, but would condense to maybe eighty yards as the lead weights stretched it down into the water. And then wed wait. And wonder and worry if all would be OK with our net.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Stories from the Deep»

Look at similar books to Stories from the Deep. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Stories from the Deep and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.