IMAGES

of America

EARLY ASPEN

18791930

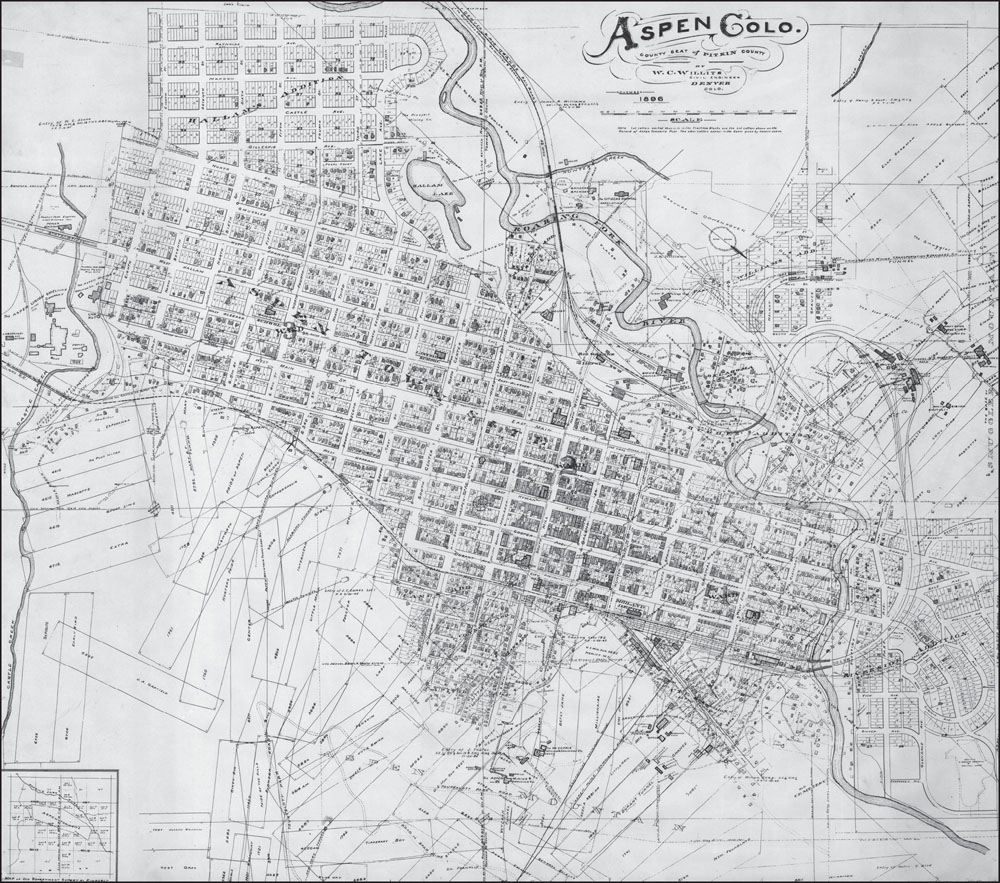

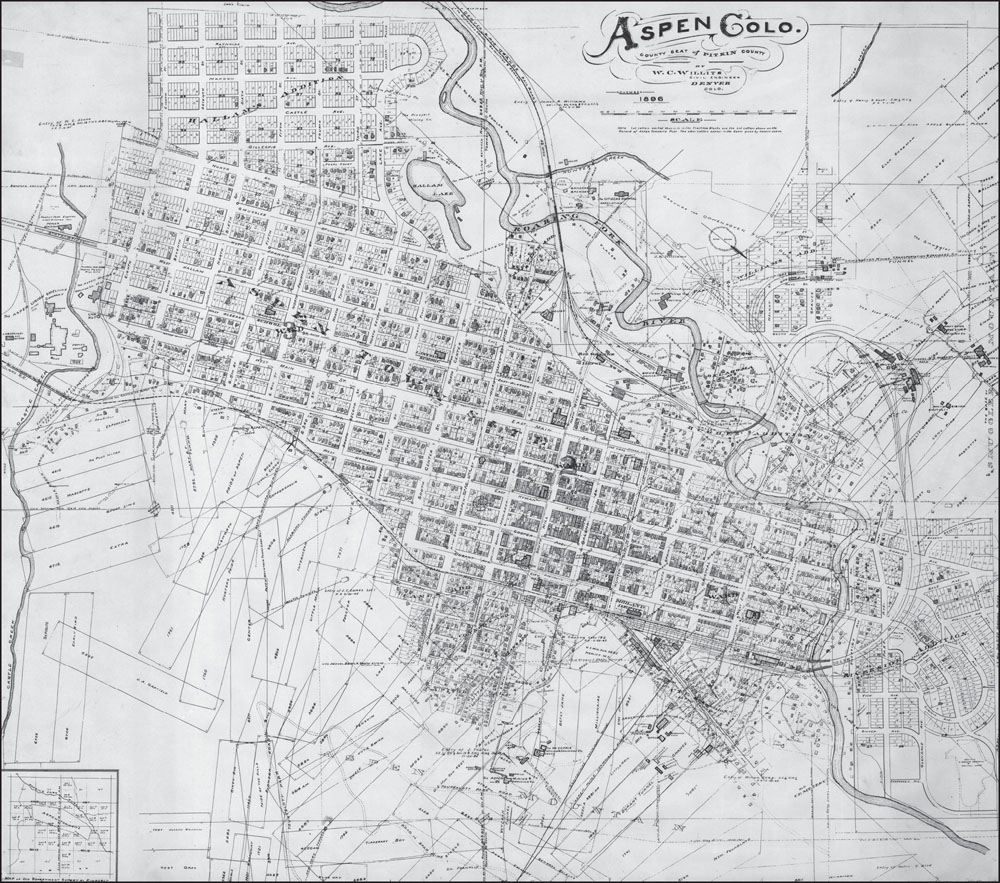

This 1893 map of the Aspen area includes streets and some buildings as well as mining claims overlaid in the town and surrounding mountains. The map provides a good view of where the competing railroads had their yards and depots. The Colorado Midland was on the south side of town with its station at the foot of Aspen Mountain. The Denver & Rio Grande was on the north side of town. (Courtesy of the Aspen Historical Society.)

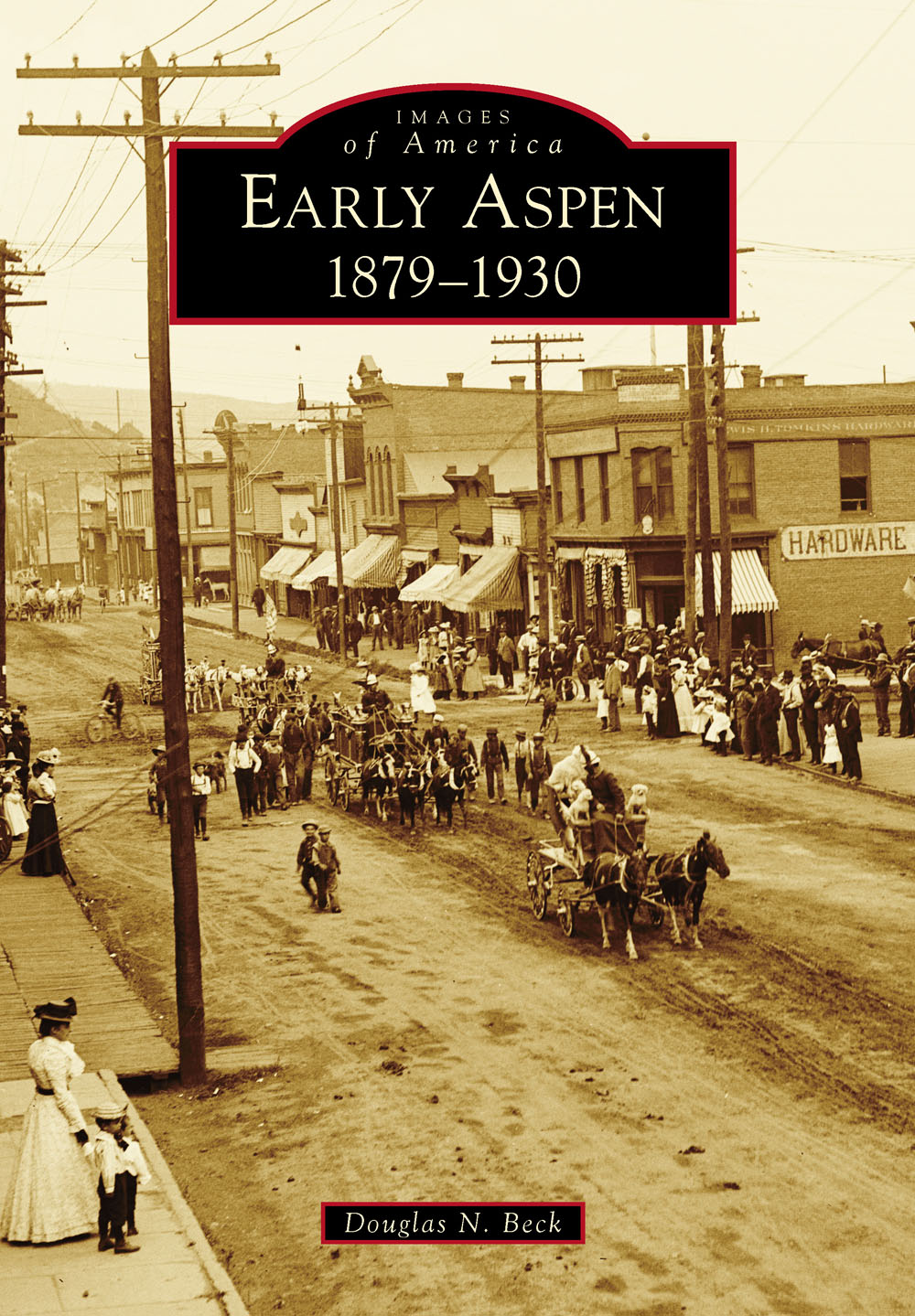

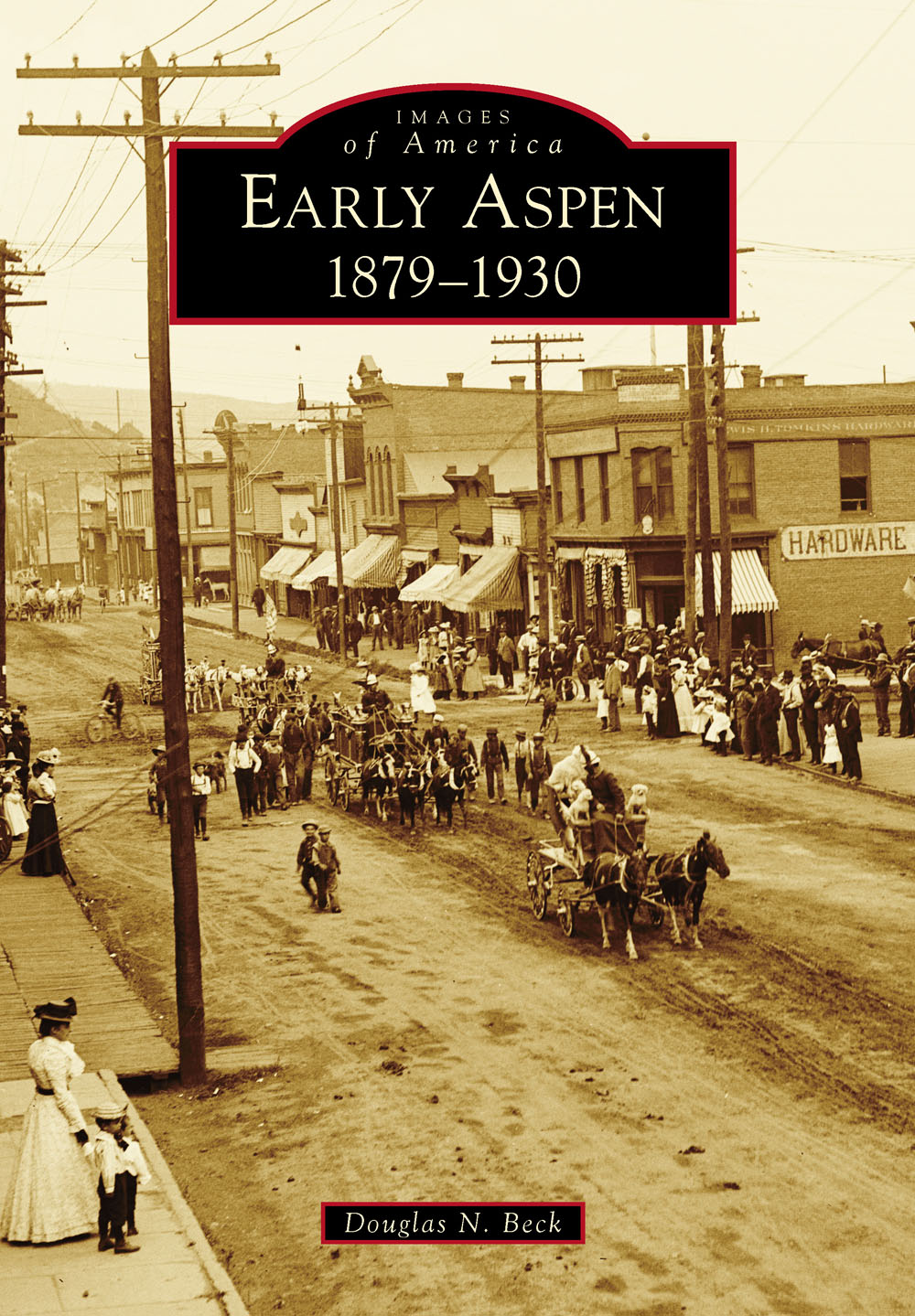

ON THE COVER: Taken August 19, 1898, this image is from a five-by-seven-inch glass-plate negative of the Gentry Brothers Dog and Pony Show parading down Cooper Street between South Galena and South Hunter Streets. Off in the distance is West Aspen Mountain, later renamed Shadow Mountain. The Independence Building is on the left with a light that says Furnished Rooms. The Tompkins Hardware store is across the street at the intersection of Cooper and Galena Streets. Even farther down the street on the right is Tom Lattas Brick Saloon, later known as the Red Onion Saloon. Note all the overhead wires, supplying direct current for both street lights and mines. Alternating current was provided for the businesses and residents. The wires may have also been for Western Union and telephone lines. (Courtesy of the Aspen Historical Society.)

IMAGES

of America

EARLY ASPEN

18791930

Douglas N. Beck

Copyright 2015 by Douglas N. Beck

ISBN 978-1-4671-3318-0

Ebook ISBN 9781439652190

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015941076

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

To my wife and best friend, Julie, for encouraging me every day and believing in me; my children, Hunter and Kira, for promising to read my books; and my father, Neil, and Uncle Paul for giving me a lifetime of memories and stories about Aspen.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My appreciation goes to my wife and children for keeping me focused. Thank you to my extended family, especially my father, Neil Beck, and his first cousin, Uncle Paul Beck. They bring Aspens history alive and give it meaning to the generations that have and will follow.

I want to thank Anna Scott and Megan Cerise from the Aspen Historical Society for helping me with hours of research, answering all my questions no matter how many I asked. They filled in many gaps and corrected some of my historical errors. Without them and the Aspen Historical Society (AHS), this book never could have happened. Thanks to Coi Drummond-Gehrig at the Denver Public Library Western History Collection (DPL) for providing a few hard-to-find images of some of Aspens most prominent pioneers. Thanks to the History Colorado Research Library for giving me a quiet place to work and access to many of Colorados historical newspapers.

I want to extend my appreciation to Mary McCarthy for providing such a valuable research tool as the Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection (www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org). This collection of many of Colorados newspapers in digital and searchable format is an invaluable tool for all Colorado history researchers and archivists.

Lastly, thanks to all of Aspens early historians who have documented so much of Aspens history. I thank them here as a group and provide individual acknowledgements in the bibliography. Unless otherwise noted, all images appear courtesy of the Aspen Historical Society.

INTRODUCTION

In Aspens early history, the region started out as a peaceful valley, home to a band of Colorado Ute Indians. Although first settled in 1879, perhaps Aspens history could actually be traced back to 1873, when Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden, following his earlier surveys of the Yellowstone area in Wyoming, focused his energy and resources on a number of expeditions in Colorado. With tacit permission from the Ute Indians, Haydens teams documented many of the natural resources as well as plants and animals within Colorado. Some of his data was later used by geologists and miners.

On July 4, 1879, a group of four prospectors arrived in the Aspen valley, having crossed the Continental Divide from Leadville, Colorado. On their first night on the valley floor, the team encountered another team that had also come over from Leadville. There is some debate over which team arrived first; either way, they arrived on the same day and within hours of one another. Avoiding the local Indians, both teams set out to stake their claims on the valley floor as well as in the surrounding mountains. In all, both teams stayed in the valley for only a few days before returning to Leadville to officially register their many claims. Names for each claim were assigned; some of the named claims would later play into Aspens mining glory and hard-fought legal battles. In 1879, the stage was set, and Aspens destiny was now in the hands of entrepreneurs, miners, lawyers, and most importantly, federal regulators.

Despite the winter of 18791880 being one of the harshest on record, miners, entrepreneurs, prospectors, and businessmen poured into the new mining camp. Some brought their families, others brought their money, and even more brought dreams of riches. Originally conceived as Ute City, the name was eventually established as Aspen. It took little time for Aspens biggest names to arrive in the valley, if not physically, then as investors in what would become some of Aspens largest mining operations. They also brought the hope of high society, hotels, banks, and eventually, railroads.

Names such as Jerome B. Wheeler, David M. Hyman, H.P. Cowenhoven and family, Henry B. Gillespie, James J. Hagerman, B. Clark Wheeler (no relation to the other Wheeler), Walter Devereux, and David R.C. Brown became etched in Aspens historygood and bad. These men, along with other pioneers, became both partners and adversaries with epic legal battles and outcomes that changed mining laws throughout the country. They were also responsible for giving Aspen a government, civic infrastructures, unionized miners, schools, churches, and social venues. They convinced Colorados biggest railroads to race to the valley to be the first to serve the mines and locals alike. These men kept more than their fair share of lawyers busy.

With the enactment of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act of 1890, there was a guaranteed market for all the silver that could be extracted from the valley at a guaranteed price per ounce. In a few short years, Aspen had over 15,000 year-round residents. There were social clubs, secret societies, multiple unions, boxing and baseball clubs, brothels, saloons, and even its share of crimes, including some notable criminals of the day. The world-class grifter Soapy Smith spent time in Aspen, as did the most famous lawman of his time, Wyatt Earp, who even owned a saloon in Aspen for a short time. People from all over the world came to Aspen.

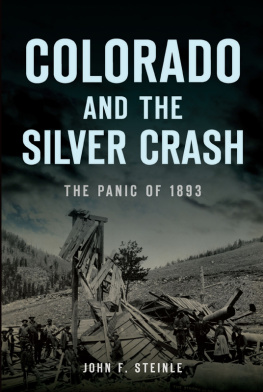

Aspen was thriving through the 1880s and into the early 1890s, and the golden age lasted until the Sherman Silver Purchase Act was repealed in 1893. Pres. Grover Cleveland was no fan of silver and set out to abolish the guaranteed purchase of the precious metal by the US Treasury. With the stroke of a pen, Aspens fortunes changed overnight. Mines ceased operations, businesses closed or were seized by creditors, and once-lavish homes were abandoned or torn down for firewood to heat the homes of those trying to stay on. Some of the wealthy investors did their best to keep their operations open, some by cutting wages and increasing working hours for the miners, others by selling more stock to unwitting investors and pouring the funds into their remaining producing mines. Eventually, all but a handful of mines shuttered. The town was nearly abandoned by the early 1900s. David M. Hyman made a few attempts to reopen some of his properties, but that was short lived. All of the big names abandoned Aspen, with the exception of the Brown family.

Next page