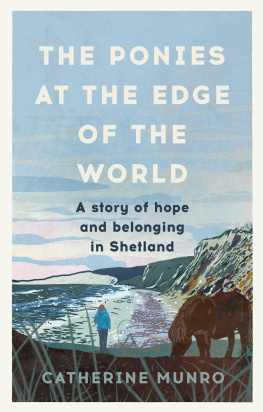

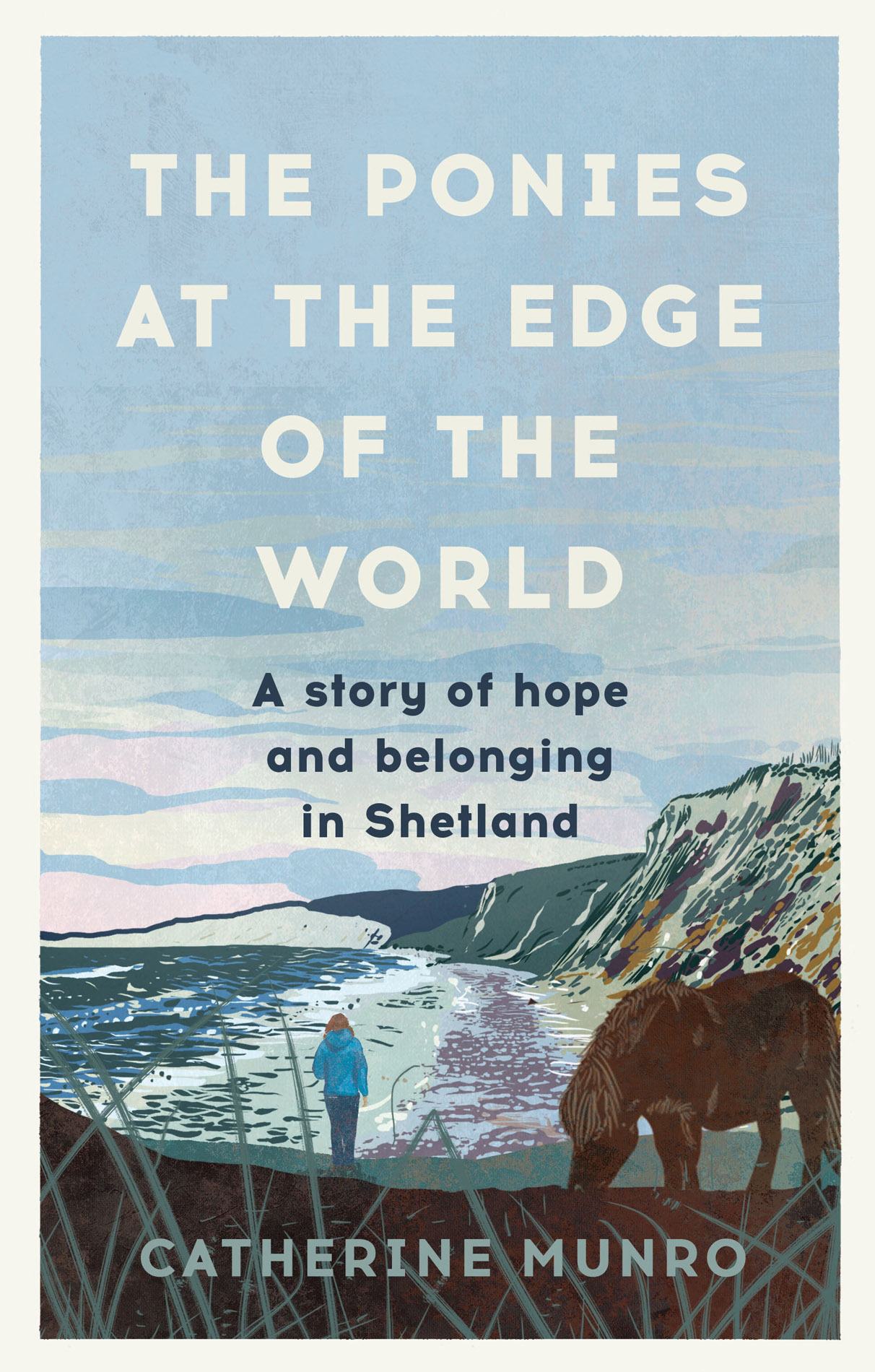

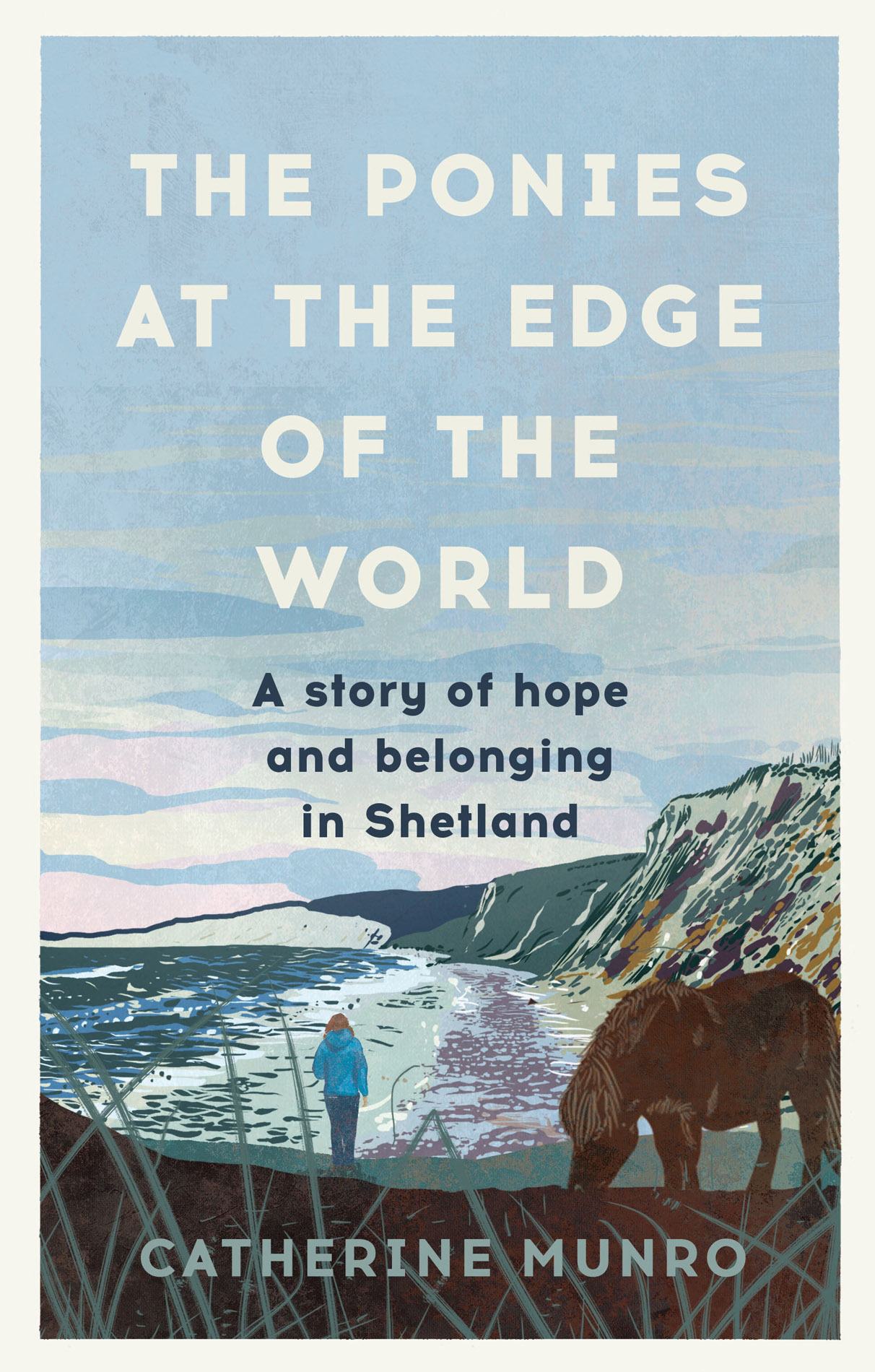

Catherine Munro

THE PONIES AT THE EDGE OF THE WORLD

A story of hope and belonging in Shetland

Contents

About the Author

Catherine Munro is an anthropologist in human-animal relationships, with a special interest in the people and ponies of Shetland. Catherine lives in Shetland with her young family and loves exploring the landscapes and sharing her experiences through her writing and work as a tour guide. The Ponies at the Edge of the World is her first book.

Introduction

I T WAS JUST AFTER 11 AM and the sun had barely risen. From its place just above the horizon it cast golden beams of light across the frosty landscape. The stillness of the night had given way to a strong gale from the east, carrying with it lashings of hailstones that periodically obscured the view in opaque, fast-moving curtains.

I was walking towards the northern tip of the isle. There the sea was visible on three sides. White-tipped waves moved urgently, with little space between them as they splashed against the rocky shore. The cold of the wind hurt my face, so I pulled my scarf closer around me, my gloved hand keeping tight hold of the bucket that the wind kept threatening to rip from my grasp.

Two Shetland ponies, a mare and foal, stood sheltered in the lee of the hill watching my approach.

Despite the storm that raged all around me, there was a sense of peace as I walked towards them. So many must have walked this way, in this weather, carrying feed for their animals. I felt my footsteps join theirs, separated only by time.

The places we live and the landscapes we love are an essential part of who we are. They capture our imagination, stimulate our senses, and become part of our experiences, hopes and dreams. The lives of others, past and present, human and animal, enter our experiences through the traces they leave. A lone rowan tree still standing to protect a croft long gone, a hat on a gatepost, hopeful for its owners return, or fresh hoofprints by the side of a loch. This book is about these connections between lives and landscapes, place and time.

In 2015 I travelled north to live in Shetland, a windswept archipelago more than 100 miles from the Scottish mainland. I came in search of ponies. The story of Shetland ponies is one of love and survival against the odds. Sharing a latitude with Greenland and with no area of land further than 3 miles from the sea, salt-drenched and windswept, Shetland is a land of extremes. This environment has, over thousands of years, shaped all who live here. For much of history, Shetlanders were entirely dependent on what they could produce from their land. This land was mostly rough, heather-covered hill, exposed to the elements and unsuitable for cultivation.

For thousands of years, ponies have been part of Shetland lives and landscapes. Living out on the open hill, ponies became smaller, helping them conserve heat. Their winter coat, mane and tail grew thicker, protecting them from the elements, and their agility and intelligence allowed them to efficiently move across the hill in search of food and shelter. Costing little to keep, with incredible strength, despite their small stature, meant they were a lifeline for crofters, transporting people and goods across the countryside and bringing home the peat, the islands only source of fuel.

Much has changed in Shetland since the days ponies brought peat home to the crofts. Ponies are now rarely used as a working animal, and crofting, the small-scale agriculture most common in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland, isnt usually a households primary economic activity anymore. Yet, the ponies from this time sometimes named individuals remembered to this day filled the stories pony breeders told me. Across the hills, ponies graze in herds, as they have done for thousands of years, and people seek to preserve valued historic characteristics in the ponies bred on the islands today. As life on the islands changes, for people and animals, adaption and innovation merge with myth and memory as, together, they continue to belong to these wild landscapes.

Ponies

I watched the line of horses walking slowly, nose to tail, out of the gate and along the tree-lined road. As the clopping of their hoofs receded into the distance, I felt tears of disappointment and frustration spill onto my cheeks.

Weekdays spent trapped in stuffy classrooms watching dust dance in the shafts of sunlight, dreams of horses distracting me from the teachers words were spent longing for this moment, when I had the chance to ride. Every weekend I was here, grooming, mucking out, carrying water, exhausting work in all weather, in the hope of joining a trek when space allowed. But the last ride of the day had just left, without me.

I returned to the stable block and sat with Max, an old, grey Highland pony whod also been left behind. He stood by me, resting his head on my shoulder. The smell of horse, the feel of his soft nose, and his warm breath filled my senses. I ran my hand along his neck, pulling out the loose hairs that remained from his winter coat, and slowly he moved his head, lightly biting my jacket, grooming me in return.

There was nobody to overhear, so I spoke to him, whispering worries I had never quite known how to put into words. As he listened patiently, our worlds merged, and I felt him understand. As surely as if he had spoken aloud, he told me to be still, that difficult times would pass and things would once again be all right. Reassurance that I badly needed but rarely heard. Perhaps because I didnt know how to ask.

I hadnt realised at the time what a lasting effect my childhood love of horses would have, how these weekends would become part of me, continuing to shape my mind, my body, and the course my life was to take. Every time the wind carries the smell of horse manure baking in the summer sun, I feel a deep sense of happiness, and the sweet smell of grassy breath from soft-whiskered noses brings an instant release of tension. Before my mind has processed the stimulus, my body responds.

If this is the love, built over weekends and summers long ago, then what is the legacy of enduring love? Sustained over generations of shared lives, human and equine, where this love is part of the story of place, entwined in the landscape and carried in the wind. This is the love I discovered in Shetland, where, on the edge of the world, people and ponies make home together.

The wind

I walked, eyes fixed forward, the details of shopfronts and the faces that surrounded me passing unnoticed. Grey concrete surroundings, the never-ceasing sound of traffic, a new day but little change. As I waited to cross a busy road, a sudden gust of wind caught my hair. Anticipating a moments relief, I turned my face towards the wind, but there was silence. The wind had nothing to say to me. I was separate from it, and it from me. Startled by this thought, I continued to walk, trying to figure out what I even meant by that. What did I expect the wind to have said? And how?

This was my first walk through Glasgow since returning from a week in Shetland, a place whose presence had hit me like a physical force. Walking the islands high cliffs, where the wind carried stories of places unseen, intangible, ephemeral, I felt connected to land, sea and sky, experienced an awakening of senses. Memories, a sense of knowing long forgotten, fleeting, impossible to hold, drifted with the salt-laden air.

Next page