FIREWATER

How Alcohol

is killing

My People

(And Yours)

HAROLD R. JOHNSON

2016 Harold R. Johnson

All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by the copyrights hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any request for photocopying, recording, taping or placement in information storage and retrieval systems of any sort shall be directed in writing to Access Copyright.

Printed and bound in Canada at Friesens.

Cover and text design: Duncan Campbell, University of Regina Press

Copy editor: Patricia Sanders

Proofreader: Kristine Douaud

Indexer: Patricia Furdek

Cover art: Portrait of Harold Johnson, by Hamilton Photographics

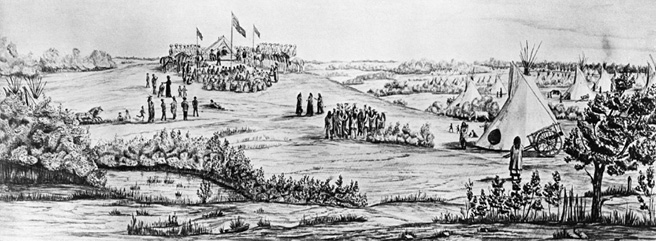

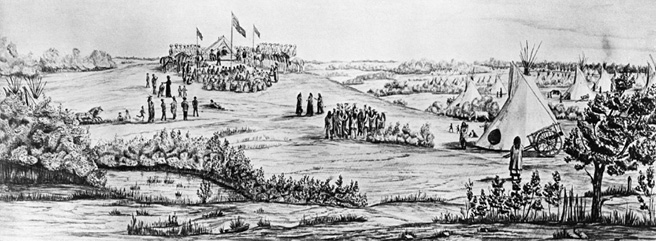

Table of contents and section page art: Treaty 6 with Saskatchewan Cree, 1876. Glenbow Archives NA-1315-19

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Johnson, Harold, 1957-, author

Firewater: how alcohol is killing my people (and yours)

/ Harold R. Johnson.

Includes bibliographical references.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-0-88977-437-7 (paperback).ISBN 978-0-88977-438-4

(pdf).ISBN 978-0-88977-439-1 (html)

1. Indians of North AmericaAlcohol useCanada.

2. AlcoholismSocial aspectsCanada. 3. AlcoholismTreatmentCanada.

4. Drinking of alcoholic beveragesSocial aspectsCanada.

5. Drinking of alcoholic beveragesHistory. 6. Spiritual healing.

I. Title.

E78.C2J625 2016 62.292'08997071 C2016-904746-6 C2016-904747-4

University of Regina Press, University of Regina

Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada, S4S 0A2

tel: (306) 585-4758 fax: (306) 585-4699

web: www.uofrpress.ca

email: uofrpress@uregina.ca

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts for our publishing program. We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada. / Nous reconnaissons lappui financier du gouvernement du Canada. This publication was made possible through Creative Saskatchewans Creative Industries Production Grant Program.

Contents

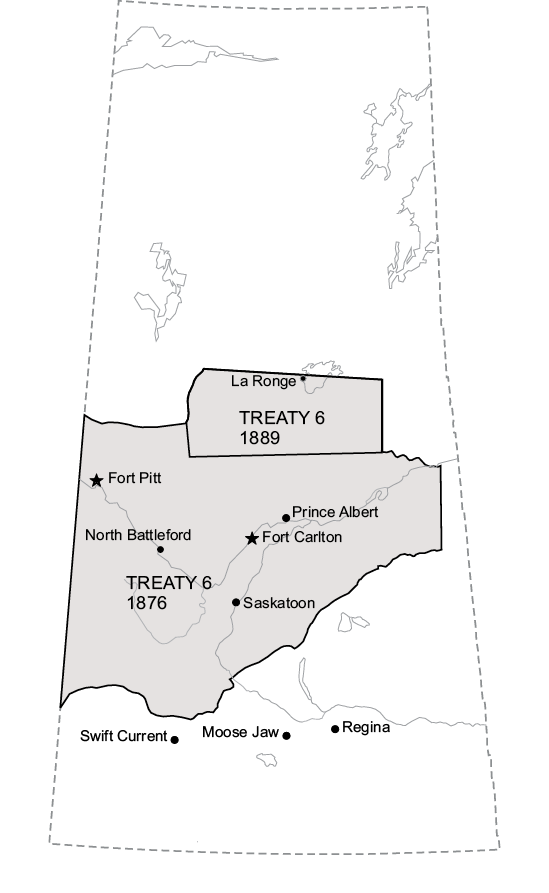

Treaty 6 territory in Saskatchewan.

Preface: The Authors First Words to His Readers

This small book is a conversation between myself and my relatives, the Woodland Cree. Its purpose is to begin a discussion about the harmful impacts of alcohol consumption and to address the extreme death rate directly connected to the use of alcohol in our northern Saskatchewan communities.

Some of what I am about to say may sound harsh when the discussion turns to the things that are being said about us. You may not want to hear those phrases repeated. I include them because the discussion I hope to begin with you will be tough. We have to discuss trauma and alcohol and death. We have to talk about where we are, how we arrived here, and where we hope to go without making excuses and calling ourselves victims. I propose that the only way forward is to take full responsibility for ourselves and our present position and begin to tell a new story about ourselves. There is no easy or soft way of doing that.

You may also wonder, who am I to speak of such things. Let me tell you this about myself and then you can go on to read more, but here and now, let me say this: When I was eight years old, my father died of heart disease. It shattered my little world. Shortly afterwards a tyrannical teacher decided to discipline me. He had me stay after class. He then took me to the bottom of the stairs, took down my pants, and strapped my naked buttocks with a piece of heavy belting. That beating I probably could have lived with, as severe as it was. But he went further. He ran his hand over my buttocks, he said to see if they were warm enough after the whipping. It was that bit of humiliation that set the disciplining apart, that made it something more , more horrible, more demeaning.

Outside, standing alone in the schoolyard, crying and humiliated, I talked to the only person I could talk to: I talked to myself. I told myself that the only reason he was able to do that to me was because my father was dead. If I had had a father, someone to look out for me, he would never have dared to do what he had done.

A few months later I was sexually assaulted by a boy six or seven years older than I. Again, unable to talk to anyone because of the humiliation, I told myself that he would never have been able to do that to me if I had had a father.

Angry, unable to tell anyone, I took it out on everyone around me. Mostly boys, but girls tooI beat up people for no other reason than that they had a father. I did it because that was the story I was telling myself. Ive told myself many stories over the yearsthat I was deprived because of poverty, that alcohol had ruined my childhoodand I acted out based upon the stories I was telling myself.

But heres the thing: I turned myself around. I was lucky. The horrible events I experienced when I was eight years old occurred before there were fancy theories floating around everywhere about trauma and victims. The problem with this latest story invented about us by kiciwamanawak that we are a product of historical traumaisnt just that it again makes us lesser people, people with a disorder. The problem is that it takes away our ability to do anything about it for ourselves. We cant fix colonization, we cant fix residential schools, we cant change kiciwamanawak opinions of us. If we are a product of historical trauma and so were then victims, we are stuck in that story with no way of telling our way out of it.

And so, yes, I was lucky, because I never was diagnosed as or labelled a victim. When I was mature enough to realize that those events had caused some of my behaviours, I quit telling myself the story that the only reason things were not the way I wanted them to be was because my father had died. I forgave him for dying and went out and found new and better stories about who I was.

I changed the story about who I was and am.

And, speaking of history and story and defining who we are, throughout the text I have used the word Indian . Some people might have a problem with the word and find it offensive. We have all heard the story that Columbus was lost and thought he landed in India and mistook us for Indians. I prefer the explanation offered by Russell Means and the American Indian Movement ( AIM ): Columbus was not lost, he knew where he was, and he called us In Dios , meaning with God. The word is not as important as the story we tell about it. Indian is also a precise legal term found in our Treaties and the Canadian constitution.

The word firewater is a direct translation of the nhithaw (Cree) word iskotwapoy , the word we use for alcohol iskot w means fire and the suffix apoy means liquid. The story I heard about how alcohol received its name tells of a time when the fur traders bartered with alcohol and were notorious for watering it down. To make sure that we were not being cheated, we would take a mouthful of the whiskey, then spit it in a fire. If the fire flared up, the whiskey was pure. If the fire went out, we knew we were being ripped off. We are still being sold firewater and we are still being ripped off, only today its not for animal peltswe pay for it with our lives and our health and our childrens lives and futures.

Next page