2017 by Carla Shalaby

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher.

Requests for permission to reproduce selections from this book should be mailed to: Permissions Department, The New Press, 120 Wall Street, 31st floor, New York, NY 10005.

The Publisher is grateful for permission to reprint the following copyrighted material:

(Something Inside) So Strong Words and Music by Labi Siffre. Copyright 1987 XAVIER MUSIC LIMITED. All Rights in the United States and Canada Controlled and Administered by UNIVERSAL - POLYGRAM INTERNATIONAL PUBLISHING, INC. All Rights Reserved Used by Permission. Reprinted by Permission of Hal Leonard LLC

Caged Bird from Shaker, Why Dont You Sing? by Maya Angelou, copyright 1983 by Maya Angelou. Used by permission of Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Images and text from Dont Let the Pigeon Drive the Bus!, words and pictures by Mo Willems. Text and illustrations copyright 2003 by Mo Willems. Reprinted by permission of Disney Hyperion Books, an imprint of Disney Book Group, LLC. All rights reserved.

Image from Dont Pigeonhole Me! by Mo Willems. Copyright 2013 by Mo Willems. Reprinted by permission of Disney Editions, an imprint of Disney Book Group, LLC. All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2017

Distributed by Perseus Distribution

ISBN 978-1-62097-237-3 (e-book)

CIP data is available

The New Press publishes books that promote and enrich public discussion and understanding of the issues vital to our democracy and to a more equitable world. These books are made possible by the enthusiasm of our readers; the support of a committed group of donors, large and small; the collaboration of our many partners in the independent media and the not-for-profit sector; booksellers, who often hand-sell New Press books; librarians; and above all by our authors.

www.thenewpress.com

Composition by dix!

This book was set in Fairfield LH

Printed in the United States of America

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

For Akenna, Izaac, Izaiah, Jordan, Sophia & Trevor

You are the young people from whom I learn love;

may you forever continue your teaching.

100% of royalties from Troublemakers will go to the Education for Liberation Network, a national coalition of young people, teachers, community activists, parents, and researchers who imagine and enact education as the practice of freedom.

Table of Contents

Guide

Contents

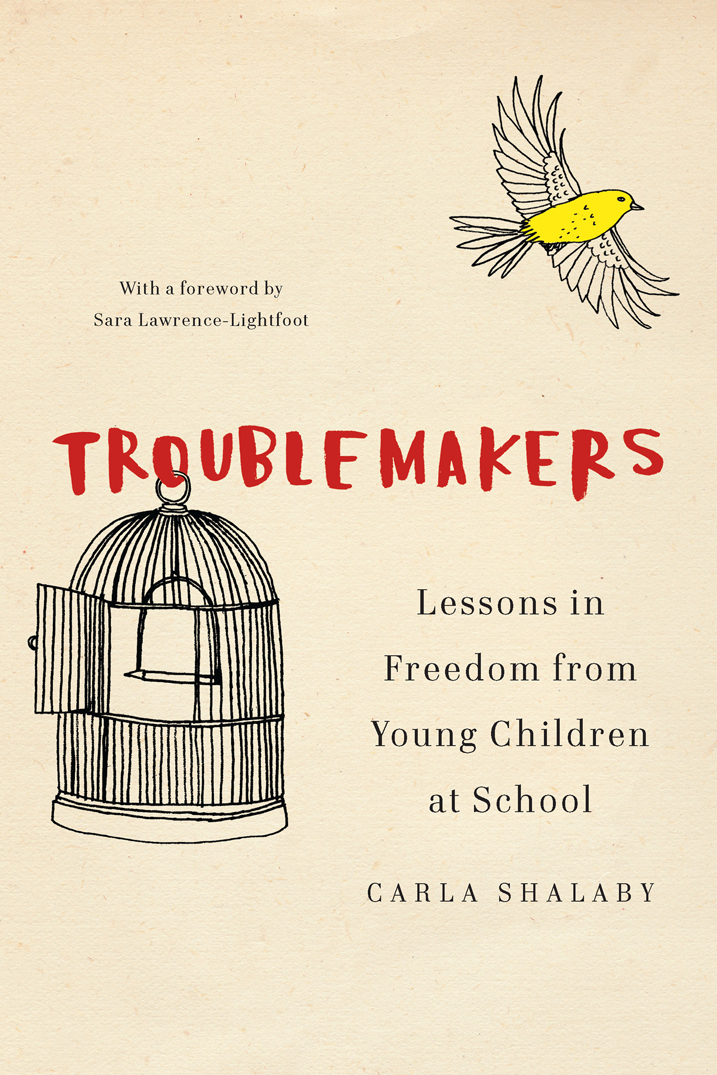

We rarely hear the words freedom and love in our private conversations and public discourses on schooling, in our aspirations and hopes for our childrens education, in our proposals and recommendations for school reform. In fact, these conceptsembedded in theoretical propositions, in moral searching, or in empirical investigationsare rarely on the tongues of educational researchers who examine the dynamics of teaching, trace the trajectories of child development, and explore the layers of school culture. In this educational era, resonating with appeals for standards and standardization, driven by the requirements of accountability and evaluation, the words, metaphors, and images that come to our minds and haunt our public consciousness carry just the opposite meaning: they speak of uniformity and conformity, management and control, of achievement and success as measured by narrow assessment tools and remote, quantifiable metrics. They tend to be blind to, and mute about, those powerful dimensions of classroom life that are shaped through intimate relationships, through community building, through honoring the rich variations and differences among us. They do not recognize or appreciate that education is a complex human enterprise requiring creativity and imagination, heart, mind, and soul, struggle and suffering, grit and grace. In our efforts to control and measure, in fact, we often confuse difference with deviance, illness with identity; we pathologize, exclude, and then label those children who do not fit the normwho trouble the waters, who misbehaveand we reward the teachers who contain and squelch the troublemakers.

In this beautiful and provocative bookincisively argued and artfully composedCarla Shalaby puts the ideas and ideals, the concepts and the practices, of freedom and love front and center. She does not offer up sentimental soliloquies on love or ideologically inspired rhetorical riffs on freedom. Rather she speaks about teaching love and learning freedom as deeply relational, respectful endeavors that must be threaded into the fabric of a humanistic education. She is referring to the kind of love that she believes should permeate every relationship between teacher and student; a love of symmetry and devotion; a love that is tough and demanding, but also enduring and forgiving; a love that makes the other person feel seen and worthy. Shalaby believes that the language and culture of love should be a part of scholarly discourses about education: love and advocacy should shine through teachers relationships with their students and love should be at the center of community building and belonging in school classrooms. She also sees classrooms as places where we must practice freedom; places where children must be treated with reverence and dignity as free persons; microcosms of the kind of authentic democracy we have yet to enact outside those walls; spaces for children to lift up their voicesindividually and collectively, in harmony and cacophonyand say what they need and who they are.

Troublemakers is in many ways an exploration of the ways in which schools are too often institutions of separation, erasure, and exclusion, not love and freedom. Shalaby draws deep and penetrating portraits of four children who have been identified by their teachers as troublemakers; her inquiry rests on the conceit that in carefully examining the perspective and experiences of these childrenas they navigate their classroom and home environments and as they build their relationships with their teachers and peerswe will learn something significant about how the cultural and structural arrangements of school may be inhospitable for allor mostchildren. Shalaby brings to the writing her signature blend of provocation, inspiration, and insight, her clear-sighted empathy and advocacy for the children. Combining portraiture, person-centered ethnography, and visual-arts methodswhich allow her to see, see with, and draw the childrenshe is an attentive listener, discerning observer, intensely curious questioner, and occasionally a playful co-conspirator. She is witness, friend, advocate, and analyst, moving across these roles with alacrity.

Even as she keeps the children in view and documents their provocations and disruptions, the drama and troublemaking they stir up, and their perspectives, voices, and reasoning, she also offers a fair and knowing portrayal of their teachers. There is no blame game here, as Shalaby closely examines the motivations, intentions, strategies, and relationship-building of teachers, and recognizes the ways in which they too get tangled in the web of norms, rules, and requirements of the institution; the ways in which they often see, and can name, the compromises, dualities, and contradictions that confront them each day even while they feel helpless in resolving the tensions productively; the ways in which they are good people trying to raise good students in a way that sometimes feels joyless and sad, difficult and demeaning.