About the Authors

Cynthia Simpson, Ph.D., is currently professor and Dean of Education in the School of Education and Behavioral Sciences at Houston Baptist University and has more than 20 years of experience in the public and private sector as a preschool teacher, special education teacher, elementary teacher, educational diagnostician, and administrator. She maintains an active role in early childhood and elementary education as an educational consultant in the areas of assessment and inclusive practices. Her professional responsibilities include serving on the National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE)/National Association of Young Children (NAEYC) Review Panel, as well as holding the position of State Advisor to the Texas Educational Diagnostician Association. She also represents college teachers as the President for Texas Association of College Teachers. Cynthia has many publications to her credit and is a featured speaker at the international, national, and state level. Cynthia has been awarded the 2008 Susan Phillips Gorin Award, the highest honor that can be bestowed on a professional member of the Council for Exceptional Children by its student membership. Her honors also include the 2007 Katheryn Varner Award (awarded by Texas Council for Exceptional Children) and the 2009 Wilma Jo Bush Award.

Jessica A. Rueter, Ph.D., is an assistant professor at The University of Texas at Tyler in the School of Education. Dr. Rueter has 15 years of experience working in public schools. Her research interests include best practices of assessment of students with disabilities and translating assessment results into evidence-based instructional practices.

Jeffrey P. Bakken, Ph.D., is professor, Associate Provost for Research, and Dean of the Graduate School at Bradley University. He has a bachelors degree in elementary education from the University of Wisconsin-LaCrosse and graduate degrees in the area of special education-learning disabilities from Purdue University. Dr. Bakken is a teacher, consultant, and scholar. His specific areas of interest include Response to Intervention, collaboration, transition, teacher effectiveness, assessment, learning strategies, and technology. He has written more than 125 academic publications, including books, journal articles, chapters, monographs, reports, and proceedings, and he has made over 220 presentations at local, state, regional, national, and international levels. Dr. Bakken has received the College of Education and the University Research Initiative Award, the College of Education Outstanding College Researcher Award, the College of Education Outstanding College Teacher Award, and the Outstanding University Teacher Award from Illinois State University. Additionally, he is the editor-in-chief for Multicultural Learning and Teaching and on the editorial boards of many scholarly publications, including Remedial and Special Education and Exceptional Children. Through his work, he has committed himself to improving teachers knowledge and techniques as well as services for students with exceptionalities and their families.

CHAPTER

Overview of Educational Laws That Affect Inclusive Classrooms

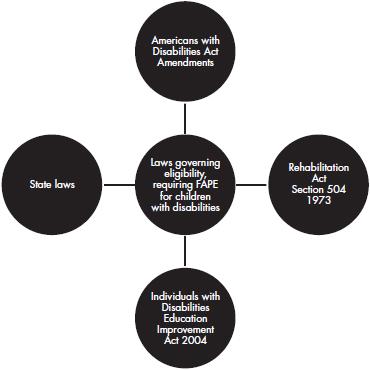

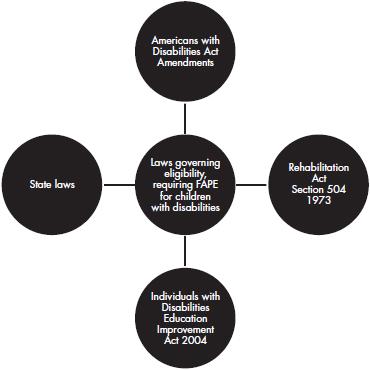

All teachers should possess a basic understanding of the laws that impact students with disabilities in inclusive classrooms. This chapter provides an overview of The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (2004), No Child Left Behind Act (2001), and two civil rights laws, (Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the Americans with Disabilities Act [1990]). illustrates the major laws applying to special education eligibility.

. Major laws applying to special education eligibility. From School Success for Kids With Emotional and Behavioral Disorders (p. 158) by M. R. Davis, V. P. Culotta, E. A. Levine, and E. H. Rice, 2011, Waco, TX: Prufrock Press. Copyright 2011 Prufrock Press. Reprinted with permission.

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

Since the late 1950s, the federal government has been involved in the education of students with disabilities. Some of the early laws included the Education of Mentally Retarded Children Act of 1958 and the Training of Professional Personnel Act of 1959. In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson signed into law the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA). This law was the first in which states received federal funding to assist in educating a certain group of students. The purpose of ESEA was to provide federal money to states to improve educational opportunities for children who were disadvantaged, including students with disabilities who attended state schools for the deaf, blind, and intellectually disabled (Yell, 2006).

On November 29, 1975, President Gerald Ford signed into law the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (EAHCA). This act is popularly known as P.L. 94-142 and was the first law that guaranteed students with disabilities a right to a free and appropriate public education (FAPE; Smith, 2001). Prior to 1975, students with disabilities had little to no access to educational opportunities. In fact, many students with disabilities were completely excluded from public schools, and those that attended public schools did not receive an appropriate education to meet their needs. The passage of P.L. 94-142 opened the doors of schools for students with disabilities (Bowen & Rude, 2006).

P.L. 94-142 has been amended several times since being enacted in 1975. In 1990, P.L. 94-142 was renamed the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). This amendment added two disability categories, autism and traumatic brain injury, and substituted the word disability for handicap throughout the law. The law also emphasized the use of person-first language. For example, the law uses student with a disability rather than disabled student, putting the person before the disability (Yell, 2006). In 1997, Congress once again amended IDEA. One of the hallmarks of the 1997 reauthorization was a specific focus on accountability and assessment practices (Sack-Min, 2007). In particular, the reauthorization of 1997 mandated that schools demonstrate measurable improvements in the educational achievements of students with disabilities (Yell, 2006). Also added was the area of transition. Starting at age 14, all students with disabilities must be involved in planning for after high school. Parents and the student, along with the special education teacher, are involved in this process.

The most recent amendment of P.L. 94-142 occurred in 2004 when George W. Bush signed the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (IDEA, 2004) into law. The changes in IDEA 2004 were substantial: there were changes in the Individualized Education Program (IEP), discipline, and identification of students with learning disabilities (Yell, 2006). IDEA 2004 was also the first time that the education of students with disabilities would be held to the same high standards as their nondisabled peers (Sack-Min, 2007). Theres no longer any debate over whether students with disabilities should have access to a classroom. Now IDEAs focus has shifted from access to accountability to ensuring that students with disabilities receive a quality education and show academic progress (Sack-Min, 2007, p. 2).

Following are important principles for school districts to understand and comply with to ensure that they meet the requirements of IDEA and provide educational benefit for students with disabilities (Yell, Ryan, Rozalski, & Katsiyannis, 2009):

Principle 1: Ensure that parents are meaningfully involved in the development of their childrens special education program.