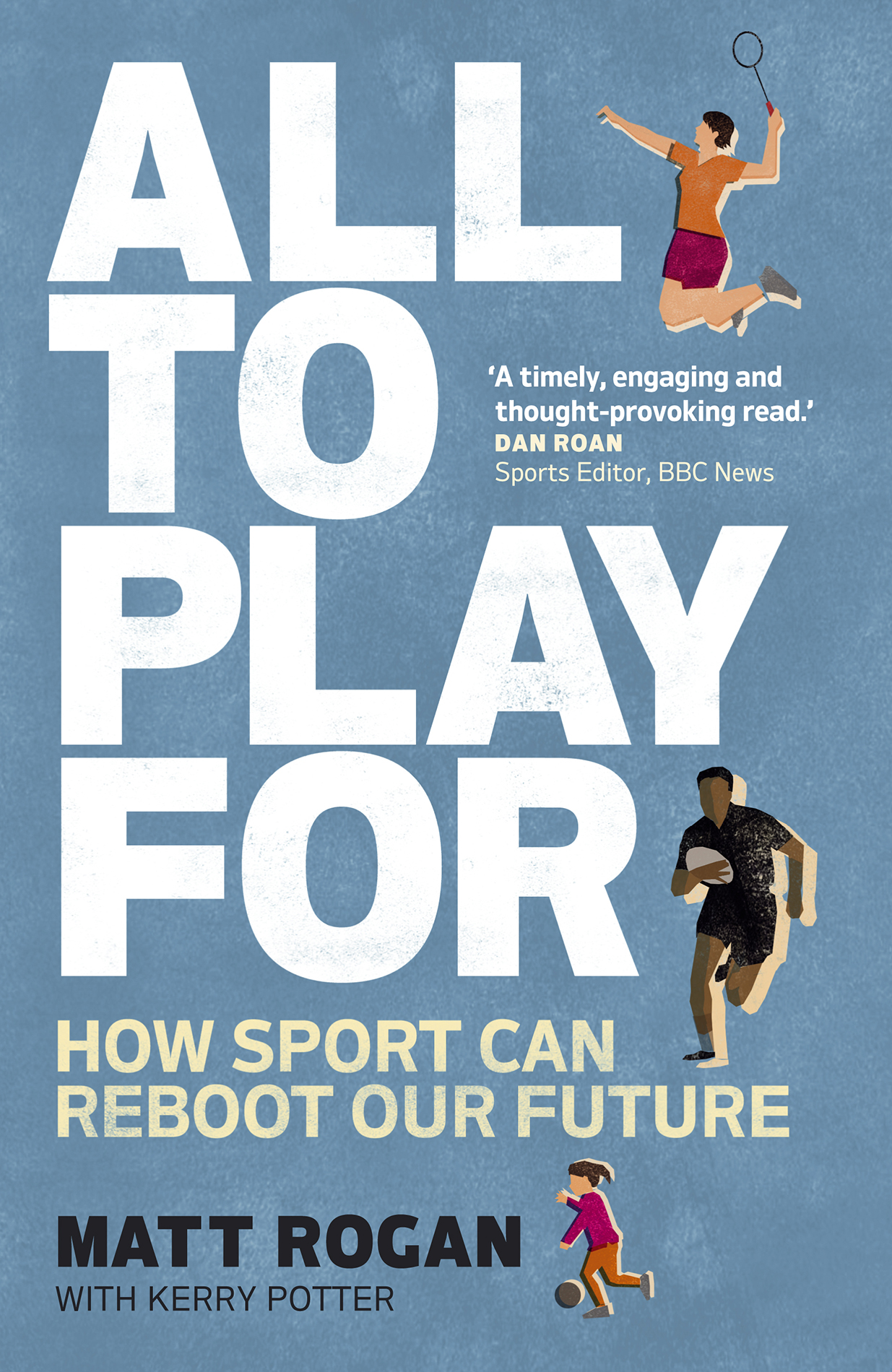

Matt Rogan with Kerry Potter

ALL TO PLAY FOR

HOW SPORT WILL REBOOT OUR FUTURE

CONTENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Matt Rogan (Author)

Matt Rogan is a well-known and respected sports business leader and the co-founder of Two Circles, the fastest growing sports agency in the UK. Over the last decade Two Circles have worked with five of the six biggest sports events in the world, as well as British household names including the Premier League and several Premier League clubs, the England and Wales Cricket Board, Wimbledon Tennis, England Rugby and a host of others. He is also a non-executive director of the English Institute of Sport, delivering technology and sport science to Britains Olympic and Paralympic teams.

Matt writes, teaches and also presents a podcast series for sports industry-leading media company SportsPro as well as several international Business Schools. He has been published by Harvard Business Review, and is an accomplished speaker and media commentator, featuring on BBC News, BBC Sport, MTV and CNN among many more. Matts previous book, written with his father Martin Rogan, Britain & The Olympic Games: Past, Present, Legacy was published by Matador in 2010.

Kerry Potter (Co-author)

Kerry Potter is the Associate Features Director on the Evening Standards magazine, ES and the former Deputy Editor of ELLE magazine. Kerry has spent two decades writing about health, fitness and lifestyle for national newspapers and magazines such as The Sunday Telegraph, The Times, The Mail on Sunday, Marie Claire, Red, Womens Health and many others.

For Conor and Niamh

Work hard but play harder

PROLOGUE: Sport is Special

Something strange was going on in London. As any Londoner knows and any tourist swiftly discovers the first rule of the Tube is that you dont talk to anyone else on the Tube. Or indeed acknowledge them in any way. Eyes averted, silence maintained, own business minded. But during the summer of 2012, when the London Olympics were in full, glorious flow, the usual rules did not apply.

At ten oclock on a balmy Saturday night, I took the Underground from one side of the city to the other, with my five-year-old and two-year-old in tow. Wed been watching the mens modern pentathlon at Greenwich Park, the climax of the Games, and were dashing to catch the last train back to our home in the countryside. It was the kind of schlep Id usually endure rather than enjoy it was way past everyones bedtime for a start but these were not normal times. The sweaty, crowded carriage had a carnival feel. People fell over themselves (literally) to give up their seats for the children. Others offered them packets of Haribo. We chatted happily to strangers, swapping memories of our days and discussing the magical fortnight of sporting alchemy wed collectively witnessed. Everyone was beaming.

Such was the power of the London 2012 Olympics; such was its transformative, stardust-sprinkling effect on the national psyche. And it wasnt an outcome many had predicted. As Simon Barnes wrote in The Games, The Times retrospective book about London 2012:

London had spent seven years being wooed by the Olympic Games and had been difficult to please, seeing only the defects of a too-ardent suitor Overnight everything changed. After this ardent but one-sided courtship, London and Britain fell without warning, fell like a ton of bricks, and the next 16 days were full of the euphoria of love requited.

It felt like a watershed moment for sport. Not just the action playing out on the pitch, track, or in the pool, but also the sense that sport as a movement could make special things happen, and that we should hold that feeling in our hearts no matter what the years ahead might throw at us. There was a precedent to these moments throughout history. When researching my previous book, Britain and the Olympic Games: Past, Present, Legacy, with my co-author (and dad) Martin Rogan, we heard stories about the 1948 Olympics and a similar feeling washing over the city, then newly scarred from the Second World War: a collective drawing of breath and of reconnection.

Somehow in the process of falling in love with London 2012 its enthusiastic volunteer army, its multiculturalism, its flood of gold medals for Team GB wed managed to break away from the drudgery of daily working life and live in the moment. We might not have officially taken those two sun-drenched weeks as annual leave, but, boy, did it feel like it. Emails went unread, feet were up on the desk, eyes glued to the TV screen rather than the computer. Weekdays may have blurred into the weekends but everyone remembers where they were on Super Saturday; that joyful summer evening when Mo Farah, Jessica Ennis-Hill and Greg Rutherford all won athletics gold after Team GB secured two in rowing and one in track cycling earlier in the day. What could be more perfect?

Moments of national cohesion and collective joy were in short supply in Britain in the years that followed. Talking to strangers on the Tube once again became a bad idea. Two referendums the Scottish independence vote in 2014, when the Scots narrowly voted to remain part of the UK and the Brexit vote in 2016, which was another close one that led to us severing ties with the European Union and had a seismic impact on the national mood. Views became increasingly polarised, with social media acting as the battleground for raging culture wars. Punches were thrown, teeth were gnashed and families argued, while economic and political uncertainty swirled all around. Social, class, wealth, generational and regional divisions became more entrenched than ever before.

And yet, it was possible to escape. While the good times had left town, sport hadnt. It was possible to dip back into that euphoric Super Saturday feeling now and then. A TV audience of 17.3 million watched the nail-biting final set of Andy Murrays first victory at Wimbledon in 2013 as Britain lay claim to its first mens winner in 77 long years. In 2018, Prince Harry and Meghan Markles wedding attracted an audience of 18.7 million, but that number was dwarfed a month later by the 20.7 million who saw Englands men narrowly exit the 2018 football World Cup at the semi-final stage.

Live sports power to pull in mammoth TV crowds is no mean feat when you consider the rise of other options catch-up, YouTube, Netflix in recent years. With audiences increasingly fractured and attention spans ever decreasing, its even tougher to hold the whole nation in thrall. Yet sport continues to magnetise us, and in relative terms is revelling in a golden age. Of the top-ten most-watched shows in the 2010s, eight out of ten were sport-based, with the 2012 Olympics closing ceremony top of the tree, pulling in 24.5 million (a staggering 51.9 million people watched at least 15 minutes of coverage during the Games thats 81.5 per cent of the population). By comparison, turn the clock back to the 1990s and sport featured only twice in the top-ten rated shows, once for football and then for Torvill and Deans 1994 Olympic bronze performance.