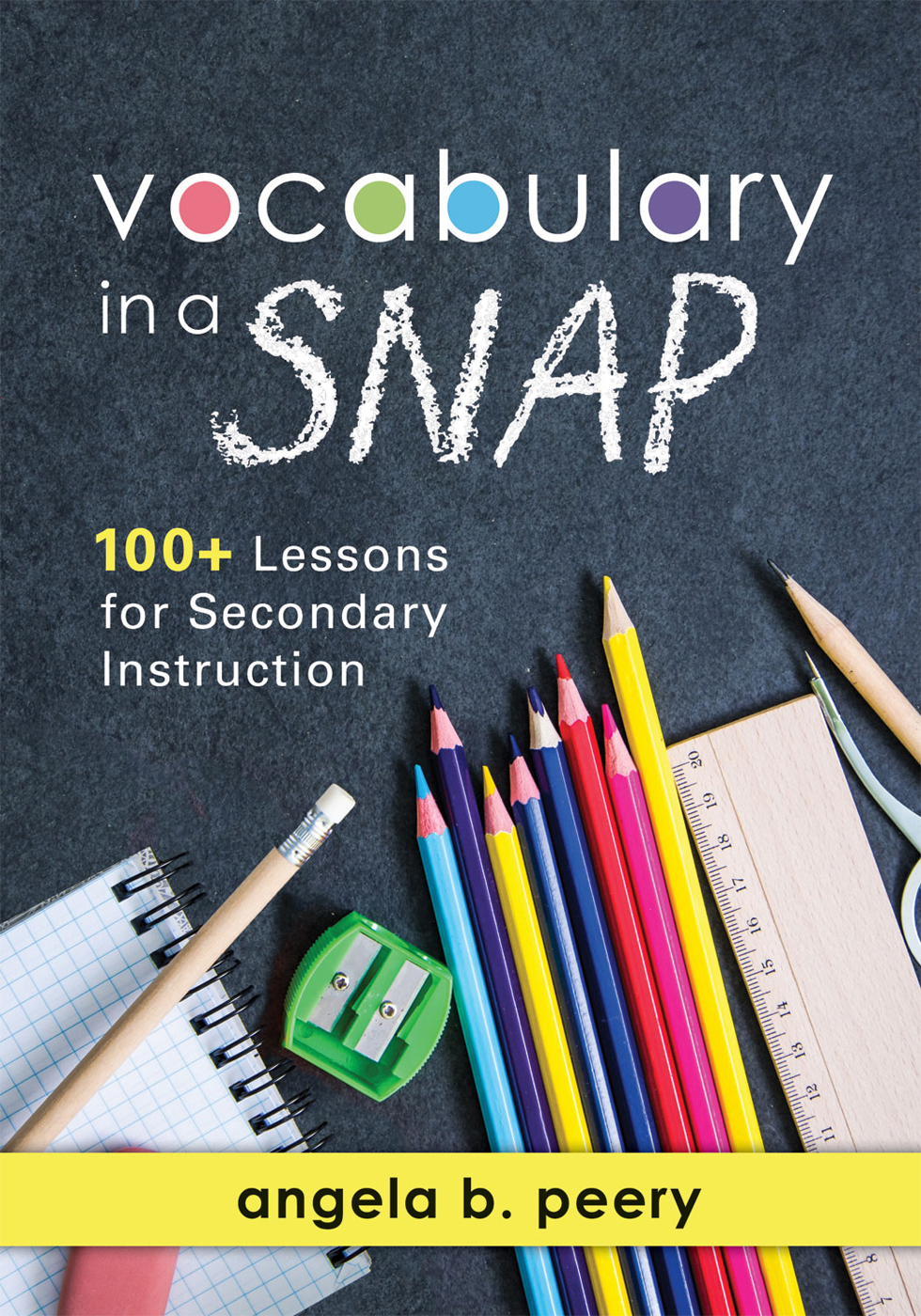

vocabulary in a SNAP100+ Lessons for Secondary Instruction angela b. peery

vocabulary in a SNAP100+ Lessons for Secondary Instruction angela b. peery  Copyright 2018 by Solution Tree Press Materials appearing here are copyrighted. With one exception, all rights are reserved. Readers may reproduce only those pages marked Reproducible. Otherwise, no part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without prior written permission of the publisher. 555 North Morton Street Bloomington, IN 47404 800.733.6786 (toll free) / 812.336.7700 FAX: 812.336.7790 email: SolutionTree.com Visit go.SolutionTree.com/literacy to download the free reproducibles in this book.

Copyright 2018 by Solution Tree Press Materials appearing here are copyrighted. With one exception, all rights are reserved. Readers may reproduce only those pages marked Reproducible. Otherwise, no part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without prior written permission of the publisher. 555 North Morton Street Bloomington, IN 47404 800.733.6786 (toll free) / 812.336.7700 FAX: 812.336.7790 email: SolutionTree.com Visit go.SolutionTree.com/literacy to download the free reproducibles in this book.

Printed in the United States of America 22 21 20 19 181 2 3 4 5  Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Peery, Angela B., 1964- author. Title: Vocabulary in a SNAP : 100+ lessons for secondary instruction / author, Angela B. Peery. Description: Bloomington, IN : Solution Tree Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2017030038 | ISBN 9781945349058 (perfect bound) Subjects: LCSH: Vocabulary--Study and teaching (Secondary) Classification: LCC LB1631 .P355 2018 | DDC 428.1--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017030038 Solution Tree Jeffrey C. Jones, CEO Edmund M.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Peery, Angela B., 1964- author. Title: Vocabulary in a SNAP : 100+ lessons for secondary instruction / author, Angela B. Peery. Description: Bloomington, IN : Solution Tree Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2017030038 | ISBN 9781945349058 (perfect bound) Subjects: LCSH: Vocabulary--Study and teaching (Secondary) Classification: LCC LB1631 .P355 2018 | DDC 428.1--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017030038 Solution Tree Jeffrey C. Jones, CEO Edmund M.

Ackerman, President Solution Tree PressPresident and Publisher: Douglas M. Rife Editorial Director: Sarah Payne-Mills Art Director: Rian Anderson Managing Production Editor: Caroline Cascio Senior Production Editor: Tara Perkins Senior Editor: Amy Rubenstein Copy Editor: Ashante K. Thomas Text and Cover Designer: Laura Cox Editorial Assistants: Jessi Finn and Kendra Slayton I was a secondary teacher and administrator for many years. As an administrator, I had the pleasure of working with and learning from Paul Browning. He knows more about good teaching than anyone I know, and he also knows how to be a dear, true friend. I dedicate this book to him.

Acknowledgments I would like to thank all the teachers with whom Ive worked on vocabulary instruction from 2015 to 2017. Every bit of feedback Ive received has been taken to heart and has made this book better. Specifically, the teachers and administrators in Orangeburg Consolidated School District Four in South Carolina have shaped my thinking immeasurably. Solution Tree Press would like to thank the following reviewers: Greg Anderson Assistant Principal Casa Grande Union High School Casa Grande, Arizona Karen Casler Special Education Teacher George B. Jarvis Middle School Mohawk, New York Juli Caveny Language Arts Teacher Mt. Olive Grade School Mt.

Olive, Illinois Tara OHea Special Education Teacher Hickory Creek Middle School Frankfort, Illinois Shondra Walker English Teacher Wonderful College Prep Academy Delano, California Blaire Zuvich English Teacher Spring Woods High School Houston, Texas Visit go.SolutionTree.com/literacy to download the free reproducibles in this book. Table of Contents About the Author  Angela B. Peery, EdD, is a consultant and author and has been a teacher since 1986. Since 2004, she has made more than one thousand presentations and has authored or co-authored eleven books. Angela has consulted with educators to improve teacher collaboration, formative assessment, effective instruction, and literacy across the curriculum. In addition to her consulting work, she is a former instructional coach, high school administrator, graduate-level education professor, and English teacher at the middle school, high school, and college levels.

Angela B. Peery, EdD, is a consultant and author and has been a teacher since 1986. Since 2004, she has made more than one thousand presentations and has authored or co-authored eleven books. Angela has consulted with educators to improve teacher collaboration, formative assessment, effective instruction, and literacy across the curriculum. In addition to her consulting work, she is a former instructional coach, high school administrator, graduate-level education professor, and English teacher at the middle school, high school, and college levels.

Her wide range of experiences allows her to work shoulder to shoulder with colleagues in any setting to improve educational outcomes. Angela has been a Courage to Teach fellow and an instructor for the National Writing Project. She maintains memberships in several national and international education organizations and is a frequent presenter at their conferences. Her book The Data Teams Experience: A Guide for Effective Meetings supports the work of professional learning communities, and her other publications and consulting work highlight the importance of teaching academic vocabulary. A Virginia native, Angela earned her bachelors degree in English at Randolph-Macon Womans College, her masters degree in liberal arts at Hollins College, and her doctorate at the University of South Carolina. Her professional licensures include secondary English, secondary administration, and gifted and talented education.

She has also studied presentation design and delivery with expert Rick Altman. In 2015, she engaged in graduate study in brain-based learning. To learn more about Angelas work, visit http://drangelapeery.com or follow @drangelapeery on Twitter. To book Angela B. Peery for professional development, contact . Introduction S ince the 1990s, teachers have realized that Look it up in the dictionary or Check the glossary are not appropriate responses when students inquire about a words meaning.

Thankfully, the weekly lists of words to study for Friday quizzes have been replaced in most classrooms with vocabulary assignments that create better retention. Teachers know that their students need to know and use more words than ever. Why have teachers come to this conclusion? Three factors have influenced most of the teachers with whom I work. First, the increasing rate of children living in poverty means that students arrive in prekindergarten or kindergarten programs already displaying a vocabulary deficit. The thirty-million-word gap, as it is known, refers to the number of words that students in welfare-dependent families have heard spoken versus the number of words that students in professional families have heard spoken before they enter school (Hart & Risley, 2003). This gap, if not addressed, is compounded over time and becomes a serious impediment to reading comprehension.

Studies show that kindergarten vocabulary knowledge accurately predicts second-grade reading comprehension (Roth, Speece, & Cooper, 2002). Anne E. Cunningham and Keith E. Stanovichs (1997) work shows a correlation between first-grade vocabulary knowledge and reading comprehension in high school. Thus, boosting our economically disadvantaged students vocabulary is incredibly important because they have an early and huge disadvantage that impacts their achievement through their teenage years. (And, ethically, boosting every students vocabulary should be part of each schools mission.) Second, academic standards have increased in rigor and demand that students have large, general academic vocabularies in addition to advanced, discipline-specific vocabularies.

The United States and other nations adopted standards have been crafted with attention to the workings of our global economy. Its simply no longer possible for the masses in most countries to get a good factory or office job with attractive benefits and comfortable pensions upon leaving secondary school. The world has changed a great deal since the 1960s, and the best jobs now require high levels of literacy and numeracy in addition to nonacademic skills like effective collaboration and technological savvy. Teachers feel pressed for time, as they always have, but they also know that the high level of literacy needed for success in academia and in the workplace requires more attention to vocabulary. And third, teachers know that students with rich vocabularies do better in many facets of life. Reading comprehension is definitely tied to the strength and size of ones vocabulary, as mentioned previously.

Next page

vocabulary in a SNAP100+ Lessons for Secondary Instruction angela b. peery

vocabulary in a SNAP100+ Lessons for Secondary Instruction angela b. peery  Copyright 2018 by Solution Tree Press Materials appearing here are copyrighted. With one exception, all rights are reserved. Readers may reproduce only those pages marked Reproducible. Otherwise, no part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without prior written permission of the publisher. 555 North Morton Street Bloomington, IN 47404 800.733.6786 (toll free) / 812.336.7700 FAX: 812.336.7790 email: SolutionTree.com Visit go.SolutionTree.com/literacy to download the free reproducibles in this book.

Copyright 2018 by Solution Tree Press Materials appearing here are copyrighted. With one exception, all rights are reserved. Readers may reproduce only those pages marked Reproducible. Otherwise, no part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without prior written permission of the publisher. 555 North Morton Street Bloomington, IN 47404 800.733.6786 (toll free) / 812.336.7700 FAX: 812.336.7790 email: SolutionTree.com Visit go.SolutionTree.com/literacy to download the free reproducibles in this book. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Peery, Angela B., 1964- author. Title: Vocabulary in a SNAP : 100+ lessons for secondary instruction / author, Angela B. Peery. Description: Bloomington, IN : Solution Tree Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2017030038 | ISBN 9781945349058 (perfect bound) Subjects: LCSH: Vocabulary--Study and teaching (Secondary) Classification: LCC LB1631 .P355 2018 | DDC 428.1--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017030038 Solution Tree Jeffrey C. Jones, CEO Edmund M.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Peery, Angela B., 1964- author. Title: Vocabulary in a SNAP : 100+ lessons for secondary instruction / author, Angela B. Peery. Description: Bloomington, IN : Solution Tree Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2017030038 | ISBN 9781945349058 (perfect bound) Subjects: LCSH: Vocabulary--Study and teaching (Secondary) Classification: LCC LB1631 .P355 2018 | DDC 428.1--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017030038 Solution Tree Jeffrey C. Jones, CEO Edmund M. Angela B. Peery, EdD, is a consultant and author and has been a teacher since 1986. Since 2004, she has made more than one thousand presentations and has authored or co-authored eleven books. Angela has consulted with educators to improve teacher collaboration, formative assessment, effective instruction, and literacy across the curriculum. In addition to her consulting work, she is a former instructional coach, high school administrator, graduate-level education professor, and English teacher at the middle school, high school, and college levels.

Angela B. Peery, EdD, is a consultant and author and has been a teacher since 1986. Since 2004, she has made more than one thousand presentations and has authored or co-authored eleven books. Angela has consulted with educators to improve teacher collaboration, formative assessment, effective instruction, and literacy across the curriculum. In addition to her consulting work, she is a former instructional coach, high school administrator, graduate-level education professor, and English teacher at the middle school, high school, and college levels.