All rights reserved. Published 1994

Berliner, Paul.

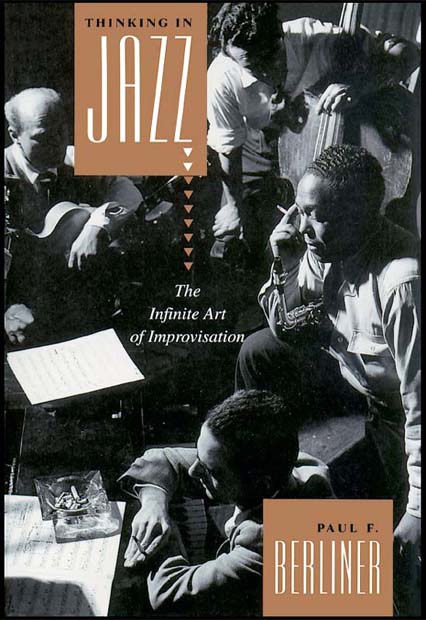

Thinking in jazz: the infinite art of improvisation / Paul F. Berliner.

p. cm. (Chicago studies in ethnomusicology)

Includes bibliographical references (p. ), discography (p. ), filmography (p. ), and index.

ISBN 0-226-04380-0. ISBN 0-226-04381-9 (pbk.)

1. Jazz History and criticism. 2. Improvisation (Music) 3. Jazz musiciansInterviews. I. Title. II. Series.

A C K N O W L E D G M E N T S

Any work of this kind, which has been in the making for many years and has depended on many different methods of data collectioneach with its own demands on time and resourcesowes its success to the cooperation and support of many individuals and institutions. I am indebted, foremost, to the musicians/interviewees named in appendix B, whose views inspired and challenged my own thinking about music throughout the study, constantly influencing its course. Readers who are not familiar with the artists by reputation will find short biographies of most in The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz (Kernfeld 1988d). Providing an invaluable background for the project was private study over the years with several other jazz musicians cited in the work: trumpeters Johnny Coppola, Julius Ellerby, and Herb Pomeroy; pianists Howard Levy and Alan Swain; and saxophonists Joe Giudice, Warren James, Charlie Mariano, and Makanda Ken McIntyre. (I did course work with McIntyre as well in graduate school at Wesleyan University.) Still others, artists Donald Byrd, Betty Carter, Dizzy Gillespie, Warren Kime, Don Sickler, Ira Sullivan, Art Taylor, Billy Taylor, and Dick Whitsell, shared ideas with me informally at nightclub and concert engagements and other venues.

Different aspects of the research were carried out under the auspices of a number of organizations. In 1978 Northwestern Universitys Office for Research and Sponsored Programs funded a pilot project, which crystallized many questions for further research. Two years later, a National Endowment for the Humanities grant supported comprehensive interviews with jazz musicians in New York City, and assistance from the United Church Board for Homeland Ministries helped with the interviews transcription. Generous sponsorship by the Spencer Foundation subsequently provided the opportunity to analyze the interview data, to initiate a component of the project transcribing recorded improvisations, and to begin preparation of a manuscript based on the studys preliminary findings. I am especially grateful to Mr. H. Thomas James, the Foundations former president, his wife, Mrs. Vienna James, and to Mrs. Marion M. Faldet, former Foundation vice-president and secretary, for their special interest in the research and commitment to its goals. My residence as a research fellow at the Rockefeller Foundation Bellagio Study and Conference Center in the spring of 1984 produced a major breakthrough in teasing out the themes of the oral history material, and, between 1988 and 1990, a partial research fellowship and supplementary assistance from Northwestern Universitys Center for Interdisciplinary Research in the Arts (under the directorships of Susan Lee and Dwight Conquergood) enabled me to integrate the oral history material with additional musicological data. The Universitys Center and School of Music helped subsidize a continuation of the transcription work and the preparation of musical examples for this book. I am especially appreciative of the personal encouragement I received throughout the study from the Schools former dean, Thomas W. Miller, and his wife, Peggy Miller, and from the current dean, Bernard Dobroski.

A number of professional jazz musicians, composers, and music theorists with jazz performance experience collaborated with me in transcribing recorded improvisations and participated in the collective process of score revision described in the headnote to of this work. Bassist Larry Gray focused largely on transcribing bass and piano parts; drummer David Fodor, the drum set parts; guitarist Stephen Ramsdell and tuba player Richard Watson, the solo parts. Joining us in editing the transcriptions were music theorist-pianist James Dossa, pianist Michael Kocour, keyboardist Shawn Decker, and saxophonist Robert Fried. An overlapping team helped prepare computer-generated music copy. Ryan Beveridge, Shawn Decker, David Fodor, Arne Eigenfeldt, and Robert Fried worked with the Finale program; James Dossa, with Score. Building on the herculean efforts of their colleagues, Fried and Dossas skillful work is largely responsible for the professional appearance of the final examples. No challenge seemed beyond their virtuoso control of the music writing programs.

To broaden the base of this studys original transcription work, I also included short excerpts from published and unpublished musical examples of several other transcribers. Credited for their fine contributions throughout are Jamey Aebersold, David Baker, Todd Coolman, Bill Dobbins, Pat Harbison, Barry Harris, Kenny Kirkwood, Thomas Owens, Lewis Porter, Don Sickler, Ken Slone, Steven Strunk, Dick Washburn, and Robert Witmer.

Because of the studys interest in bridging such worlds as music theory, performance practice, composition, cognition, history, cultural interpretation, and so on, I sought criticism from colleagues with different specializations who kindly agreed to serve as readers. I am grateful to them for sharing their responses with me and raising various issues for consideration during the works revision. At Northwestern University, sociologist Howard Becker, composer Michael Pisaro, music theorist Richard Ashley, historian Sarah Maza, and choreographer and dancer Lynne Blom read individual chapters. Giving an entire draft of the manuscript a thorough reading were jazz keyboardist-composer Joan Wildman at the University of Wisconsin, Madison; ethnomusicologist and jazz bassist Robert Witmer at York University, Toronto; ethnomusicologist and jazz trumpeter Ingrid Monson at the University of Chicago, and, at the same institution, Keith Sawyer, a doctoral candidate in the Department of Psychology; Stephen Ramsdell and James Dossa; and three participants in the original interviews, pianist Howard Levy, trumpeter Bobby Rogovin, and drummer Paul Wertico. Pianist Barry Harris also looked over many portions and made important recommendations for revision. Additionally, Christopher Rudmose brought her fine editorial eye to several chapters, and folklorist Linda Morley generously shared her talents by meticulously examining the last two drafts of the work and making sensitive editorial suggestions throughout.

Over the years, I have also derived inspiration from discussions with several associates with common interests in ethnographic research and in jazz. They include sociologist Howard Becker and performance ethnographer Dwight Conquergood at my own institution; musicologist Lawrence Gushee and ethnomusicologist Bruno Nettl at the University of Illinois; ethnomusicologist Christopher Waterman at the University of Washington; bassoonist and music history professor Joseph Urbinato at Roosevelt University; and composer T. J. Anderson, formerly at Tufts University. Additionally, many friends have consulted on one point or another or shared records and other pertinent materials with me. The limitations of space prevent my acknowledging each by name, but, at the very least, let me thank my colleagues Karen Hansen, Eddie Meadows, Thomas Owens, Lawrence Pinto, Lewis Porter, Don Roberts, Bob WeIland, and fellow Barry Harris workshop members cited in this work, Franklin Gordon, Jeff Morgan, and Al Olivier. Also, I would like to express special gratitude to David Dann of station WJFF 90.5 FM in Jeffersonville, New York, who assisted me in tracking down essential discograpbical information; to David Pituh and Ruth Charloff, who brought great powers of concentration to proofing the final manuscript and made valuable editorial recommendations; and to Michael Kocour, who contributed the photograph that appears in . Students in my improvisation courses at Northwestern University have also been a constant source of stimulation, expanding my own understanding of the subject.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48-1992.