ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Layne Cameron is an avid outdoorsman who has authored or coauthored five books and more than three hundred articles for national magazines and newspapers, including Scouting magazine and Boys Life. The Hoosier native has enjoyed assignments ranging from riding and mapping Indianas mountain bike trails to ballooning New Mexicos redrock canyons, from ice fishing Minnesotas walleye-laden lakes to barefoot waterskiing in Floridas tea-colored waterways.

Camerons first exposure to geocaching was a January 2001 brief in Outside magazine (If You Hide It, They Will Come). Later, while mountain biking in southern Indiana, Cameron spotted a GPS-toting hiker who at first glance seemed to have lugged along a five-gallon bucket. After further inquiry, Cameron confirmed that he had spotted his first geocacher, who had performed the exchange ritual and claimed a small prize as his own.

Cameron works as the science and technology writer for Michigan State University.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks to my wife and my boys for supporting me through this entire project and for allowing me to drag them into geocaching and other outdoor adventures time and time again. Im also grateful to Scott Adams at Globe Pequot Press, who believed in my work and knew I could write this book.

1

Geocaching: The Global Sensation

Before we can talk about the birth of geocaching, we must first look at the creation of the satellite navigation systems that made the activity possible.

GPS: A Twentieth-Century Miracle

In the early 1960s, President John F. Kennedy announced his new goal of putting a man on the moon before the end of the decade. The U.S. military, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and the Department of Transportation adopted a to the moon mentality and turned their collective attention toward the development of a satellite navigational system. Their objectives for the system included global coverage; continuous usage; all-weather capability; land, maritime, and aeronautical applications; and, of course, high accuracy.

In 1964 the U.S. Navy launched the Navigation Satellite System, better known as Transit, the first space-based satellite system. Since we were in the midst of the Cold War and the space race, the Soviet Union matched these efforts with the creation of its Tsikada system.

Both systems provided the first two-dimensional, high-accuracy positioning service. The major downside to these systems was that it took ten to fifteen minutes for a receiver to process an estimated position. This slow processing was acceptable for maritime navigation because of ships relatively low speeds, but unacceptable for the high-speed realm of jet airplanes. As the navy began upgrading Transit, the air force developed its own system, and the army also began working on alternative navigational systems.

In 1969 the Office of the Secretary of Defense established the Defense Navigation Satellite System (DNSS) program, whose goal was to consolidate the militarys independent efforts into a single, shared system. The Navigation Satellite Executive Steering Committee (NSESC) was created to determine the viability of DNSS. In one of those rare instances of a governmental committee actually doing some good, the NSESC birthed the concept of the Navigation Signal Timing and Ranging Global Positioning System, commonly known as NAVSTAR GPS. (Reviewing the committees meeting minutes, however, produces no record of discussions related to recreational aspects of the new technology. Apparently, the specter of the Cold War and the race for the moon consumed the members time and kept them from creating a fun, outdoor treasure-hunting game. For that oversight, we must give the committee an A rather than an A-plus.)

It wasnt until 1978, though, that the first GPS satellite was launched, and it took another six years before President Ronald Reagan announced that a portion of GPS capabilities would be made available to the civilian community. About that same time, products for civilian consumers began appearing on the market.

Once completed, the GPS system consisted of twenty-four satellites orbiting at about 12,500 miles above the earth in six orbital planes. Each satellite completes one orbit every twelve hours.

Back on the ground, GPS units work by receiving satellite signals, measuring relative arrival times, and computing the location of the user. By receiving signals from at least four satellites, early GPS units could determine three-dimensional geographic coordinates to within 100 meters.

As the United States developed GPS, the Soviets progressed from their Tsikada system roots to create GLONASS (Global Navigation Satellite System), a space-based system quite similar to GPS. Like its capitalistic counterpart, GLONASS was inspired by the military and is still managed by Russias Ministry of Defense. GLONASS also consists of twenty-four satellites but differs from GPS by using three orbital planes rather than six.

With the Flip of a Switch, Geocaching Is Born

In 1996 President Bill Clinton penned Presidential Decision Directive NSTC-6, Americas GPS policy. One of the policys goals was to incorporate the use of GPS in peaceful civil, commercial, and scientific applications worldwide.

As a result of this directive, President Clinton ordered the Defense Department to turn off Selective Availabilitythe jamming signal that prevented recreational users from pinpoint accuracyon May 1, 2000. The announcement was made via a White House news release: Today, I am pleased to announce that the United States will stop the intentional degradation of the GPS signals available to the public beginning at midnight tonight.... This will mean that civilian users of GPS will be able to pinpoint locations up to ten times more accurately than they do now.

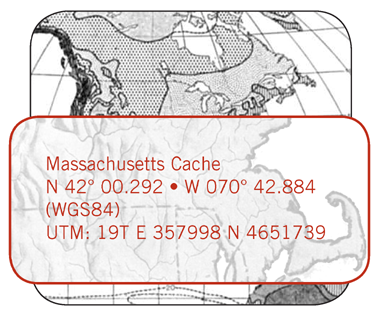

Quite literally with a flip of a switch, GPS users saw higher position accuracy and improved speed or velocity of tracking. Portable GPS units could lock in on a target within 5 to 10 meters. The decision to discontinue Selective Availability is the latest measure in an ongoing effort to make GPS more responsive to civil and commercial users worldwide, wrote President Clinton. This increase in accuracy will allow new GPS applications to emerge and continue to enhance the lives of people around the world.

Thanks to the demise of Selective Availability, GPS units now receive more precise information that can put you within 5 to 10 meters of your target.

As history was being made, self-professed techno-geeks like Dave Ulmer, an electronics and software engineer from Portland, Oregon, followed the announcements. Ulmer stayed up late that night just to watch his GPS units accuracy improve. The improvement was dramatic indeed, Ulmer said. I soon realized that there should be applications for this increased accuracy that were previously impossible.

After brainstorming new ideas for this budding technology, Ulmer came up with the idea of a treasure hunt. The next day he practiced finding locations from various directions, verifying that everything worked. On May 3 he placed a five-gallon bucket near a wooded road about a mile from his home. Inside the bucket were a logbook and some trinkets for trading. He dubbed his game The Great American GPS Stash Hunt.