NEVER CRY

NEVER CRY

HALIBUT

AND OTHER

AND OTHER

ALASKA HUNTING & FISHING TALES

BJORN DIHLE

Text 2018 by Bjorn Dihle

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Dihle, Bjorn, author.

Title: Never cry halibut : and other Alaska hunting and fishing tales / Bjorn Dihle.

Description: Berkeley : Alaska Northwest Books, [2018]

Identifiers: LCCN 2017043435 (print) | LCCN 2018001441 (ebook) | ISBN 9781513260945 (ebook) | ISBN 9781513260921 (paperback) | ISBN 9781513260938 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Dihle, Bjorn. | Fishers--Alaska--Biography. | Hunters--Alaska--Biography.

Classification: LCC SH415.D54 (ebook) | LCC SH415.D54 A3 2018 (print) | DDC 639.2092 [B]--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017043435

Edited by Kristen Hall-Geisler and Olivia Ngai

Cover art: Red monkey/Shutterstock.com; Meilun/Shutterstock.com; Tribalium/Shutterstock.com; K N/Shutterstock.com

Interior graphics: ducu59us/Shutterstock.com; Red monkey/Shutterstock.com

Published by Alaska Northwest Books

An imprint of

GraphicArtsBooks.com

Graphic Arts Books

Publishing Director: Jennifer Newens

Marketing Manager: Angela Zbornik

Editor: Olivia Ngai

Design & Production: Rachel Lopez Metzger

CONTENTS

CONTENTS

For my folks, Nils and Lynnette Dihle.

BLACKTAILS AND BROWN BEARS

MY DAD GREW UP in Sacramento reading stories about hunting and fishing in Alaska. In the early seventies, as strip malls and suburbia ate up the fields and woods surrounding his home, he persuaded my mom to move north. They were both kids, newly married and ripe for adventure. Alaska had untrammeled landscapes where people could wander, hunt, and fish where they pleased and not see another person for weeks. There were massive herds of caribou, and plenty of wolves hunting them. There were Dall sheep and thousands of miles of mountains. There were brown bears and blacktail deer, and to my dad it sounded like paradise.

Alaska didnt quite have the same ring for my mom.

Well try it for a year, my dad promised. If we dont like it, we can always move back.

Reluctantly, and much to the disapproval of her family and friends, she agreed. Southeast Alaska seemed as far away as Russia, and between the bears, bugs, weather, and the price of a plane ticket, a trip north wasnt high on their circles list of vacation destinations.

They loaded their tiny AMC Gremlin with a giant malamute and a high-strung Norwegian elkhound and drove out of the suburbs. Following the Alaska Highway, they slowly motored through forests and mountains that seemed to stretch forever. In Fort John, British Columbia, the dogs rolled in something dead, making the final push to the Alaskan port of Haines a bit fragrant. Aboard the state ferry, they motored south down Lynn Canal, an expansive, storm-ridden fjord, with mountains towering up to seven thousand feet on both sides. Clouds clung to Admiralty Islands rainforest mountains as the ferry made a hard turn toward the small city of Juneau.

They settled there, cut off from the rest of the civilized world by a 1,500-square-mile icefield and a wilderness archipelago. It was late fall, the nastiest time of the year in Southeast. Having nowhere to live, they pitched a tent at a campground and slept with their dogs for nearly a month before they found a small rundown trailer. Their slate-gray rainy world was a hard adjustment for my mom, and a lifelong love-hate relationship with Southeast Alaska began as she watched snow creep down mountains and stared at a glacier in her backyard.

It was one thing to read about Alaskan hunting adventures and another thing to make your own. The forest and mountains, tangled and shrouded in constant storms, were nothing like the Sierras. My dad was armed with an ancient rifle with a bolt that was clunky and problematic. On one of his first ventures, he wandered through walls of alders, clawing brush, and gloomy old-growth forest to the top of a mountain to look for mountain goats. His excitement of finally going hunting in Alaska was not dampened by his inability to see more than a hundred feet in the foggy alpine. After spending the day sitting in the rain and snow, hoping a goat would appear out of the gray, and watching ravens glide in and out of view, he hurried down with an empty pack. After his being chilled and lightheaded from low blood sugar and wandering through a dark, dripping forest, a respect for how quickly even a day hunt could go awry was born.

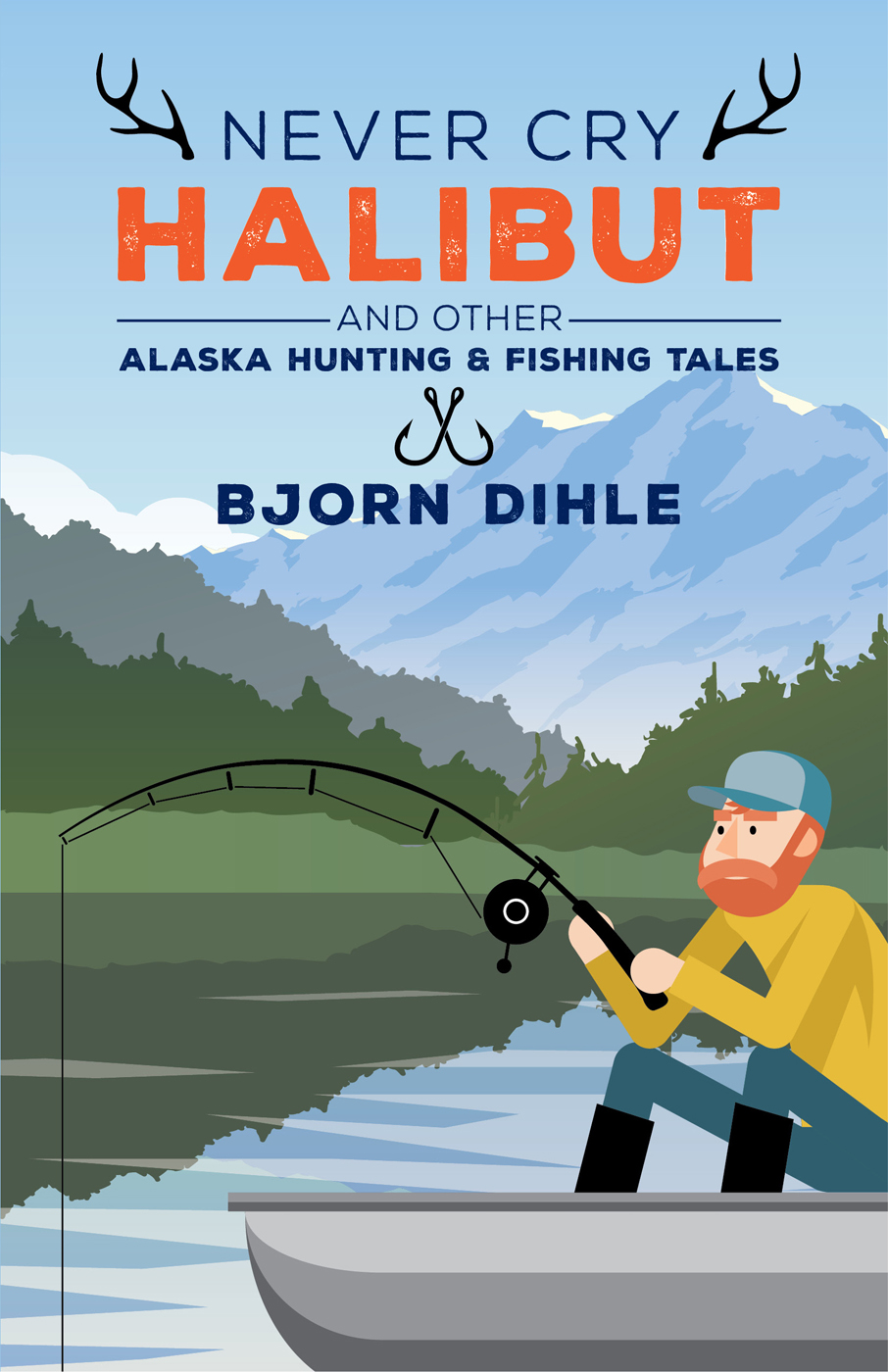

A year later, having yet to harvest any Alaskan big game, my dad and his friend Joe skiffed across Stephens Passage to Admiralty Island for a fall deer hunt. Having heard stories of brown bears and frustrated with a gun that barely worked, hed upgraded to a .338 Magnum. They anchored the boat offshore and carried a raft over popping seaweed and slick rocks. Ravens spoke their ancient language from spruce boughs, and eagles stared mutely out to sea. Higher on the beach in a sandy section, my dad knelt and studied large tracks unlike anything hed seen. Brown bears. He knew this island, at a hundred miles long and twenty miles wide, was said to have the densest concentration of coastal grizzly bears in the world. Fresh deer tracks, tiny in comparison, wended along the high tide line. After agreeing on a return time, Dad pushed through the guard timber and stood on a well-worn bear trail paralleling the beach. Squinting into the sodden forest, he checked his rifle, took a breath, and walked into the dark maze.

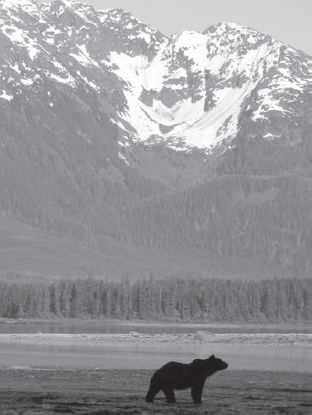

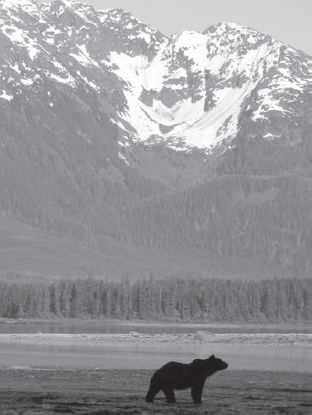

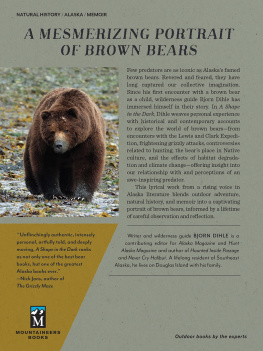

A brown bear superimposed against the mountains of Admiralty Island.

He traveled slowly over windfallen trees and through blueberry brush, alert and focused for any movement or sound. After hours of sneaking along without seeing a deer or meeting a bear, he came to the edge of a meadow and stopped to look and listen. The wind was still. A raven croaked, and an eagle cried its strange, haunted cry. Nothing unusual. He eased through shore pines and deciduous brush, and his rubber boot sunk into the muskeg. Slowly, he pulled his boot out, making a soft sucking sound. A flash of brown streaked across the meadow. Seeing it was a buck, he instinctively raised his rifle, and when the crosshairs rested on the blur of its vitals, he pulled the trigger. A moment later, the deer disappeared.

Next page

NEVER CRY

NEVER CRY

AND OTHER

AND OTHER