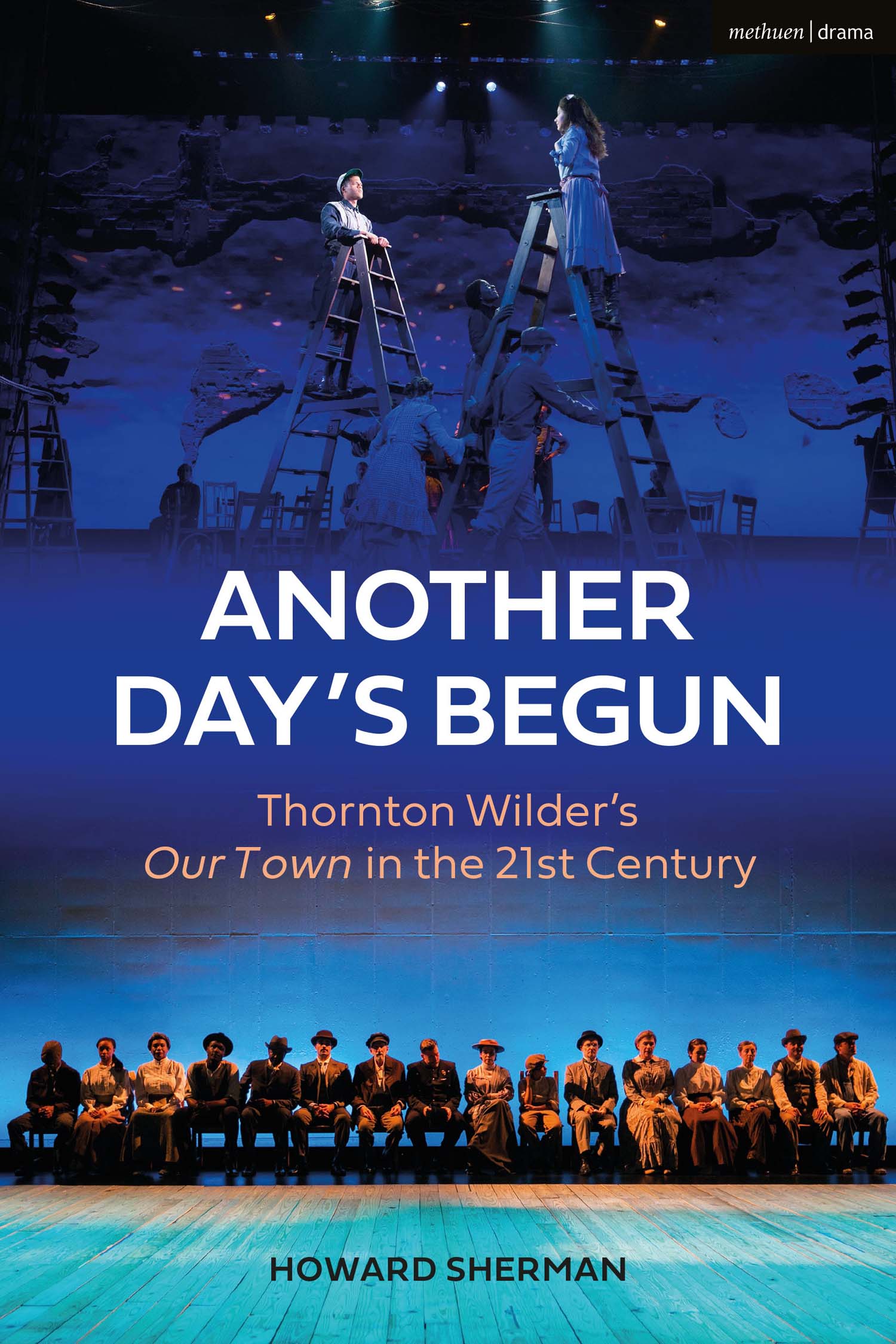

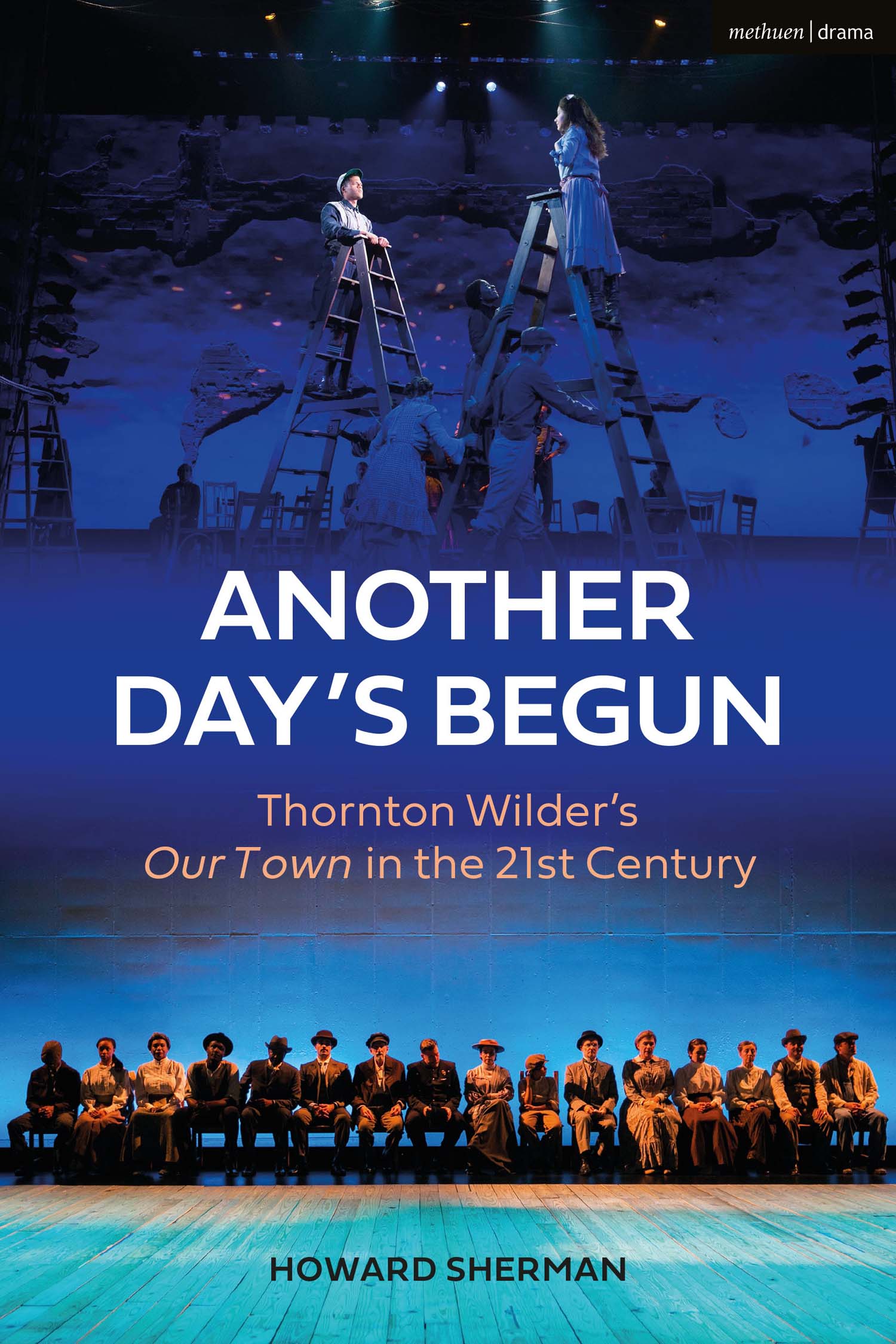

Another Days Begun

About the Author

Howard Sherman is a theatre administrator, writer, and advocate.

He has been executive director of the American Theatre Wing and the Eugene ONeill Theater Center, managing director of Geva Theatre, general manager of Goodspeed Musicals, and public relations director of Hartford Stage, as well as interim director of the Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts. He has also held administrative positions at the Westport Country Playhouse, Manhattan Theatre Club, and Philadelphia Festival Theatre for New Plays.

Since 2012, he has been the US columnist and a feature writer for The Stage newspaper in London, and in 2018 was named contributing editor of Stage Directions magazine. His writing has appeared in a number of other publications including Slate, the New York Times, the Guardian, and American Theatre magazine.

Howard frequently consults, writes, and speaks on issues of censorship and artists rights in both academic and professional theatre and he created the Arts Integrity Initiative in 2015 to focus on those efforts. He has delivered keynote addresses for, among others, the Educational Theatre Association, KCACTF, Florida Association for Theatre Education, and the Texas Educational Theatre Associations Arts Program Administrators Conference. He was cited as one of the Top 40 Free Speech Defenders in 2014 by the National Coalition Against Censorship and received the Dramatists Legal Defense Funds Defender Award in 2015.

A native of New Haven, Connecticut, and graduate of the University of Pennsylvania, Howard resides in New York with his wife, producer Lauren Doll.

www.hesherman.com www.artsintegrity.org

Contents

Introduction: This Book Is

Called Another Days Begun

It has become fashionable to knock Thornton Wilders Our Town as sentimental, old-fashioned, golden-hued, sepia-toned, done-to-death nostalgia. It has also become fashionable to write about how Our Town is improperly and ignorantly relegated to the status of sentimental, old-fashioned, golden-hued, sepia-toned, done-to-death nostalgia.

It is derided as fodder only for high school theatre. Yet, Arthur Millers The Crucible and Reginald Roses Twelve Angry Men (now often done as Twelve Angry Jurors) are less than twenty years younger than Our Town, and are also frequently produced in high schools, but it doesnt seem that people feel the incessant need to haul out a narrow set of stereotypes, or anti-stereotypes, which still repeat canards about them when those plays are produced professionally. The former drama may forever be placed in the context of the McCarthy era, and the latters original white male dynamic will often be explained as a product of its time, but they are more dramaturgical notes than the lede in reviews of productions or the reasons offered as to why the plays should not be done.

Our Town does offer a certain challenge when one looks for an easy way to encapsulate or explain it, since it defies easy synopsizing. It has certainly proved a challenge for many. The poster for the 1940 film version billed it only as The screens most unusual picture, in an era when willful misrepresentation in marketing was the norm. In TV Guide magazine in 1959, a televised version was described as, The Stage Manager starts, interrupts, halts and comments on the activities of the players, who represent the residents of Grovers Corners, N.H. A minimum of scenery and props is employed. The website of Concord Theatricals, which licenses the play for stock and amateur productions, offers up, Narrated by a stage manager and performed with minimal props and sets, audiences follow the Webb and Gibbs families as their children fall in love, marry, and eventually in one of the most famous scenes in American theatre die.

To be sure, no one- or two-line precis can possibly do justice to any great literary work. After all, the whole point of synopses is to be reductive, to simplify. But perhaps more so than any classic American dramatic work of its era, Our Town proves slippery precisely because it doesnt have a conventional plot, a singular through-line of narrative, only glimpses, out of chronological order, with a foray into fantasyor is it? It was meta-theatrical even before people spoke in such terms, experimental without being so ostentatiously avant-garde that its innovations have calcified with time. For those who value it, it is remembered not for its story but for its message.

Of the last, there can be no mistake about what Thornton

Almost as if concerned that audiences might miss this essential query, asked to another character onstage but truly meant for the people watching the play, Wilder proffered a series of queries in an essay for The New York Times which ran only nine days after the play opened. It was titled, somewhat curiously, A Preface for Our Town. Its odd in that it assumes those who will take in the play might need some preparation, not only in its style, but in its philosophy, in the questions that Wilder himself wished to explore. What is the relation between the countless unimportant details of our daily life, on the one hand, and the great perspectives of time, social history, and current religious ideas, on the other? he asked rhetorically. What is trivial and what is significant about any one persons making a breakfast, engaging in a domestic quarrel, in a love scene, in dying? It is a veritable study guide for the play.

Perhaps in that era, this preface didnt linger, the way it would today on the internet, for every person who sought to see or participate in a production of the play to reference. But Wilder would write a more permanent preface to the 1957 compilation Three Plays by Thornton Wilder, which grouped together Our Town with The

In the final revised version of Our Town, the standard text for production, Thornton Wilders nephew, Tappan, literary executor of his uncles work, offers yet a bit more elaboration on the 1957 preface, drawn from unpublished notes in his uncles archives. In it, the younger Wilder asserts that the line about an attempt to find value above all price is the single most quoted line in theatre programs for Our Town. But instead of calling it preposterous as he did originally, Thornton would later call the attempt absurd. Yet he acknowledges in a handwritten note that audiences possess even greater vision than the plays characters, that Emily learns that each lifethough it appears to be a repetition among millionscan be felt to be inestimably precious.

Our Town, it would seem, is about everything, wherever, whenever, and whomever you may be, and for goodness sake, pay attention.

* * *

Who were the greatest American playwrights of the 20th century? It is likely, were one to take a casual survey among theatre scholars, practitioners, and knowledgeable fans, that the answer would be something along the lines of ONeill, Williams, Miller, Albee, and Wilson, with apologies for the biases that blinkered who could reach the stage for the majority of those 100 years. But ask about the greatest American plays of the 20th century, and you might hear Long Days Journey into Night, The Glass Menagerie, A Streetcar Named Desire, Death of a Salesman, Whos Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, The Piano Lesson and Our Town

Next page