Daniel Boone

Daniel Boone

AN AMERICAN LIFE

MICHAEL A. LOFARO

Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant

from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Copyright 2003 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre

College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University,

The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College,

Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University,

Morehead State University, Murray State University,

Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University,

University of Kentucky, University of Louisville,

and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 405084008

03 04 05 06 07 5 4 3 2

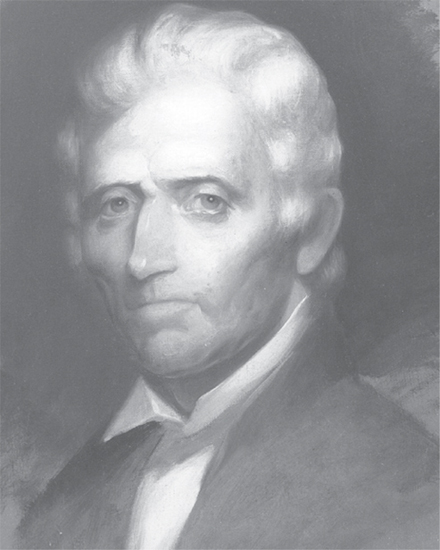

Frontispiece: Daniel Boone. Oil on canvas by Chester Harding, 1820.

MHS image number 386. Courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lofaro, Michael A., 1948

Daniel Boone : an American life / Michael A. Lofaro.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index.

ISBN 0-8131-2278-3 (alk. paper)

1. Boone, Daniel, 1734-1820. 2. PioneersKentuckyBiography.

3. Frontier and pioneer lifeKentucky. 4. KentuckyBiography. I. Title.

F454.B66L628 2003

976.902092dc21

2003008805

This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper

meeting the requirements of the American National Standard

for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America

| Member of the Association of

American University Presses |

Again, and always, for Nancy

CONTENTS

PREFACE

Daniel Boone! The very name evokes and echoes the epic exploration of the American West. Just as the existence of a changing frontier has always exerted a great influence upon the American people, no one, from the time of Capt. John Smith to the present day, is more central to the frontier experience than Daniel Boone. He is commonly regarded as the prototype and epitome of the American frontiersman, a near ideal representative of the westward movement of the nation.

The facts are impressive. Nearly seventy of his eighty-six years involved the exploration and settlement of the frontier. In 1734 he was born on the western perimeter of civilization in Berks County, Pennsylvania. At the age of thirty-one he ventured as far south as Pensacola, Florida, in search of a new home. And when he died in 1820 he was living on the western boundary of civilization in St. Charles County, Missouri, one of the outposts for outfitting expeditions to explore the Rocky Mountains. Boone seemed constantly to place himself upon the cutting edge of civilizations advance and did so with relish.

Boone also typifies the inner conflict between civilization and the wilderness of many of the early hunter-explorers. He was both the pioneer who paved the way for civilized life and the natural man who preferred the simplicity and rugged vitality of wilderness life as an end in itself. To Boone, the frontier was simultaneously a challenge and an inspiration, something to subdue and improve and to preserve and enjoy.

His paradoxical relationship to the wilderness often accurately reflects a basic and perhaps even stereotypical American attitude toward the frontier. If for Europeans the frontier was a boundary that indicated territorial limits, for Americans of Boones day and their descendants, a frontier was more an area that invited and even demanded exploration. The real and continuing desire to penetrate the unknown in quest of new land and wealth motivated discoverers from many nations, but took on renewed meaning for those facing the vast wilderness of America. This same desire provides both a tangible and a spiritual link between the first walk into the forests surrounding Jamestown in the seventeenth century and the first walk on the moon, the zenith of exploration of President Kennedys New Frontier of the twentieth century. Daniel Boones life was permeated by this same frontier spirit and as such provided and still provides one extraordinarily popular model of national self-definition for his countrymen and women.

Regrettably Boones unique relationship to his own historical periodthe significant events in his life and their consequent bearing upon the development of Americais often a blur in the popular mind. Chronologically, few place him as Washingtons contemporary or the one who encouraged Abraham Lincolns grandfather to move to Kentucky. Fewer still remember that the march of civilization into the trans-Appalachian West and beyond, areas opened by Boone and his fellow Long Hunters, also brought with it the legal mechanisms used so dexterously to strip Boone of the nearly one hundred thousand acres of land he had acquired under what he thought was just claim. And yet he was never long defeated or discouraged. If the lawyers took his land or if the settlers who followed the trails he had blazed ruined the hunting, there was always more land and better hunting to be found farther west.

It quickly becomes evident in examining the life of Daniel Boone that he was the continual victim of a restlessness that occurred whenever the population around him grew too dense. As his uneasiness with civilization increased, he remedied the situation by plunging farther into the wilderness. But in so doing he blazed a trail for others to follow. His example and fame unintentionally encouraged rapid settlement, which only renewed his restless spirit and forced him to move deeper into the forest. This outline of the general progression of events in Boones life is far too simplistic to reflect accurately the total picture of his motives for exploration. It does show, however, the historical pattern that serves as the basis for the ambivalent attitude toward the frontier that marks Boones image in biographies from 1784 to the present day, and provides an overview of the ironic cycle that at times seems to have dominated the frontiersmans life.

Irony and ambiguity permeate Boones life story. Although remembered and enshrined for his role as a pioneer, he often was happiest following the same wilderness life as Native Americans. With them Daniel was comfortable and familiar, coexisting far more in mutual respect than in warfare. As someone who bridged and understood both native and pioneer cultures, Boone sought to avoid bloodshed, to negotiate solutions to conflicts, and literally to hold on to a shrinking geographical and cultural middle ground as the violence of native-settler conflict and of the Revolutionary War in the West escalated around him in Kentucky. His move to Missouri in 1799 resonates with the same dualities. In addition to renewed economic opportunities in this next Promised Land, Boone found a new borderland, a land that, like Kentucky decades earlier, struck a tenuous balance between civilization and the wilderness; Daniel found as well some of the same Shawnees and Delawares who, like him, although by different means, had been displaced by the pressures of land speculators and waves of new settlers.