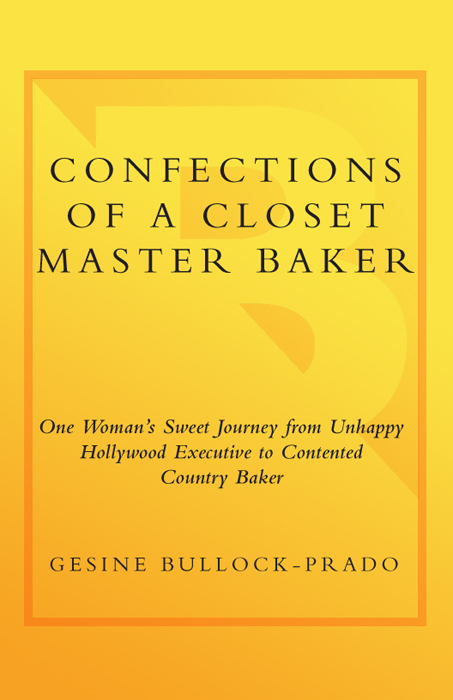

PROLOGUE

The Devil in St. Nick SAW THE DEVIL AT AGE THREE and he gave me chocolate. It changed my life forever.

SAW THE DEVIL AT AGE THREE and he gave me chocolate. It changed my life forever.

On the evening of December 6, 1973, in Salzburg, Austria, something stood at the landing just outside the door of our Shillerstrasse apartment, let loose an agonizing moan, and rattled a ghastly chorus of heavy chains. My mother whooped in delight and invited me to open the door.

Sina! Mach auf!

I was no stranger to this kind of perversely dark German childhood experience. My first storybook, Struwwelpeter, told such heartwarming tales as The Story of the Thumb Sucker in which a naughty boy gets his thumbs cut off when he persists in that odious habit. Illustrations included. Or the story of the rascal Kaspar who, upon proclaiming he will no longer eat his soup, wastes away and dies, again accompanied by beautifully detailed artwork. And, theres Pauline who insists on playing with matches. She certainly deserves to be consumed by those bright orange flames that take her to a fiery death. These children were not alone in their misdeeds; I myself was an avid nail biter. And, as my cousin Suzanne liked to remind me hourly, I once pooped on the Persian rug in the foyer. I was a toddler. What did I know?

But even worse, in the estimation of my majestically gorgeous and perpetually svelte mother, I was sugar obsessed. I was both grotesquely undisciplined and a potential fatty, effortlessly breaching two cardinal sins in my mothers endless ledger of unforgivable venialities. To hide my growing addiction I became a candy thief, taking primarily from the secret sweets drawer in my aunts credenza and sometimes from my friend Katyas bedside table stash. It was for these ugly crimes that I had been anticipating an untimely end similar to those of Kaspar, Pauline, and that poor thumb-sucking boy. And now the devil had come to my door; my mother had apparently subcontracted her daughters grisly disposal.

I wasnt going to help invite death in. My sister, five years older, wiser, and intent on setting unspeakable terrors upon me, opened the door herself. She was acquainted with our dark caller; shed experienced him both as jolly Santa in America and as his cranky German alter ego, Saint Nikolaus. Either way, the outcome was usually pretty good for her on both sides of the Atlantic. We had dual natures ourselves; equal parts German and American, a bit of both our mother and our father. Our German mother, a professional opera singer, carted us to Europe while she toured, and our Alabama-born father kept the stateside fires burning in Virginia, toiling inside the rings of the Pentagon.

My sister opened the door just in time for us to spy a gruesome creature layered in chains, a filthy burlap sack strapped to his back and a leather collar cinched about his pockmarked neck. Attached to the collar was a leash, and as I followed the length of rope to the hand that grasped the lead, I beheld what appeared to be the devil himself. Our visiting demon was lank and gray-bearded, draped head to toe in sooty red velvet robes and sporting an impractically tall pointed hat. He left two matching velvet stockings leaning against the door jamb, brimming with chocolates bearing his likeness and countless other sweets. Once he and his henchman were safely out of child-snatching range, I braved the open hallway to grab the loot.

But before I could marvel at the bounty, I stood to face our benefactor. If I was going to take his offering, I felt obliged to overcome my fear and acknowledge his generosity by looking him straight in the eye, devil or not. He had gone through all the trouble of finding us. Hed probably checked in Virginia first. And then hed have tracked us to Germany and followed the trail to Austria. And he could have left us coal. But he gave us chocolate. All of this and he was going to leave it at our door without taking credit for his trouble and kindness.

Gr Gott, Herr Teufel. Vielen dank.

He scoffed at my greeting, literally translated, Greet God, Mr. Devil. Many thanks.

Gr Gott, Ferkel. Little piglet, he called me a little piglet. Sure, it was a term of endearment, but I was anything but a little piglet. He knew that.

And so it followed that he was anything but a devil. In fact, he was a misunderstood angel; he was the great Saint Nikolaus accompanied by his festering sidekick Krampus. And to put the final dusting of luster on this confectionary miracle, my mother allowed us unlimited access to the contents of our velvet stockings.

I had less spectacular run-ins with confections while in Europe that I remember in an equal amount of detail: my fourth birthday cake, rimmed with marzipan clown heads and filled with almond cake and cream; the After Eight mints hidden in the credenza of the study in my aunts home in Bergen, Germany, top drawer of the middle row, behind the Christmas napkins; the stockpile of gummi bears in my grandmothers handbag, which she doled out as bribery to keep me walking on the harsh cobblestone streets of Nrnberg during shopping expeditions. She herself kept a bar of the blackest bittersweet chocolate to bolster her own shopping spirits.

Martha, our American nanny, conjured slim packages of lemon creamfilled wafers from the pockets of her prairie skirts to coax me along on our daily visit to see my mother during her matinee performance. We crossed the river Salzach on the footbridge that connects the old Salzburg to the new. I portioned each wafer perfectly to coincide with our walk to the Landestheater, one tiny nibble to every ten footfalls on the narrow cobblestone streets. Once we reached the metal stairs that clung to the side of the building and led to the stage door, I would modulate my bites to coincide with the ring of every fourth step. I lifted my knees high and let my foot land squarely on the tread so that the sonorous metal ring would vibrate through my body and add more drama to the crunch of each bite.

Inside, the backstage hallways teemed with men in period costume, their britches open exposing girdles buckling from strain. Sweat streaked their heavily pancaked faces and loosened the glue holding their handlebar mustaches fast. Martha would usher me hastily past my mothers empty dressing room and through a side door into the theater, where I would slip into an empty seat for my afternoon nap. I might wake to see her mid-belly dance, or engaging in a lusty kiss or suffering a consumptive death. Once, I woke during a rehearsal of Carmen to see my sister among the gypsy children on stage, dramatically lunging for prop coins being thrown her way. The director invited us both to join a slew of other vagabonds to round out the cast, but I suffered from painful shyness and a general distrust of strangers. My sister had no such problems and took to the stage with hammy delight. At home, she emptied her pockets on her bed and revealed that the fake lucre she was scooping up on stage was in fact beautifully wrapped chocolates. Had I only known the rewards awaiting me, I might have conquered my timidity. I had, after all, faced a devil for chocolate only to find that I was in the presence of a saint. And in the end it was the example of unlikely angels and the power of confections that led me on a sweet path to happiness and grace in my adult life.

SAW THE DEVIL AT AGE THREE and he gave me chocolate. It changed my life forever.

SAW THE DEVIL AT AGE THREE and he gave me chocolate. It changed my life forever.